BORN

(OR LIVED) IN BERDICHEV

MOYSHE NOTOVITSH

May 22: Birth of the literary researcher and critic Moyshe Notovitsh in Berdichev (1912). A graduate of the Moscow Pedagogical Institute, he taught at the theater school attached to GOSET, the State Yiddish Theatre in Moscow and finished his career as a lecturer at the Kazan Pedagogical Institute in Tataria. His literary yerushe includes a study of I. J. Linetski and a collection of critical essays on Soviet Yiddish literature. (Linetski was an anticlerical satirist, sprung from Hasidic roots, of the late nineteenth century. His most prominent work, the novel dos poylishe yingl, was being reprinted as late as 1939.) Notovitsh died in Kazan in 1968.

AVROM GONTAR

March 20: Birth of the poet and prose writer Avrom Gontar, in Berdichev (1908). Gontar began to publish his verse in 1927 and eventually authored more than twenty books. In the thirties, he edited the magazine farmest. The poet did military service during the Great Fatherland War and afterwards worked on the newspaper of the Jewish Antifascist Committee, eynikayt, which led to his arrest by the Stalinists. In the sixties, Gontar served as an editor of sovetish heymland, the largest Yiddish literary monthly of its time. Gontar died in Moscow in August 1981.

YOSL KOTLYAR

February 12: Birth of the writer Yosl Kotlyar (in Berdichev, Ukraine, in 1908). Kotlyar was a beloved children's poet, who wrote, among other works, likhtike geboyrn; entuzyastn; glentsndiker veter; kinder fun mayn land; mayn velt; lider-mayselekh; oysgeleyzte erd. Kotlar died in Vilne on June 15, 1962.

JACOB BACHMANN

BACHMANN, JACOB (1846–1905), Russian hazzan and composer of synagogue music. Bachmann served as a boy-singer with the hazzan of his native town of Berdichev. He developed a phenomenal voice and was admitted to the Petrograd Conservatoire in 1864. Anton Rubinstein became his teacher and later took him on his concert tours as a solo singer. Bachmann, nevertheless, decided to be a hazzan and established his reputation at the synagogues of Berdichev, Rostov, and Constantinople. During his stay at Lemberg until 1884, Bachmann founded a mixed choir and took up composition. As successor to Osias Abrass at Odessa (1884–85) he was acclaimed by the public.

He later settled in Budapest. Bachmann's voice is said to have covered the entire range from dramatic tenor to powerful bass, highlighted by an extraordinary echo-falsetto. His compositions are influenced by Rubinstein, the "Westerner" in Russian music. Bachmann was eager to show command of contemporary musical devices (Schirath Jacob, pp. 54, 79, 89, 95, 96), including reminiscences of Bach (ibid., p. 188) or Meyerbeer (ibid., p. 89), and was able to write striking, though rather conventional, choral settings (ibid., pp. 18–19). However, Bachmann has to be judged by his improvisations in traditional hazzanut, a small part of which is included in his printed works. Bachmann's cantorial recitative was at its best at the sublime moments of the High Holy Days' liturgy (ibid., 159–64. Works: Cantata (Ps. 45) for the silver jubilee of Francis I (1879); Schirath Jacob (1884); Uwaschofor godol (1889); and Attah Zokher (after 1905). Unpublished works are in manuscripts in David Putterman Library, N.Y.

REB NISI BELZER

Famous cantor and composer-director, Reb Nisi Belzer in Berdichev. There is a paragraph in “My Life Story” by the famous artist, Boris Tomashevsky that describes how, when he joined Nisi Belzer's choir as a young child, Nachum Matenko was already there:

“Within the choir there were certain gifted individuals. One of them was Nachum Matenko. He had a very rare bass-baritone voice. He was a very handsome man and he wore modern clothes with a top hat. His long hair, artistic brow and graceful deportment elicited great respect and admiration. Looking at Nachum, one could assume that he was an artist of the Kaiser's Opera rather than a chorister in Reb Nisi Belzer's choir. When Nachum left Reb Nisi, he was appointed Cantor of the Great Odessa Synagogue in the place of the renowned Cantor Bochman. The Moscow millionaire, Poliakov, heard Nachman's voice in the Odessa Shul and was so impressed by his talent and personality that he built a synagogue in his courtyard and installed Nachum as Cantor, giving him a life-long contract.”

NISSAN SPIVAK

(1824-1906), cantor and composer.

He was cantor in Belz, Poland, and was generally known as ‘Nissi Belzer’.

Later he was cantor at Kishinev (now in Moldova) and from 1877 at Berdichev

(now in the Ukraine). In his childhood he had an accident which damaged his

voice but he had an extensive reputation primarily as a composer and choir conductor.

It was his vocal handicap that led him to develop original synagogue music in

which the choir, instead of being merely an accompaniment or used for responses,

was assigned lengthy ensembles - with solos and duets - reducing the role of

the cantor. Spivak attracted many students to Berdichev and took his choirs

to other centers, including Hasidic courts.

ALEXANDER TAIROV (ALEKANDER KORENBLIT)

Courtesy: NEW TIMES (by Lyudmila Ivanova)

The 20th century knew five great directors who laid the foundations of modern theatre of Russia. Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko and their two followers Meyerhold and Vakhtangov. And Tairov, a dilettante who was nobody’s follower and launched the unique Chamber Theatre, which showed the world as a unity in variety and proclaimed the value of personality, and whose productions were mostly described as brilliant. Though the theatre and the director have been gone for more than half a century, there still remains a mystery.

It all started with The Demon. Soon after Alexander Korenblit, 10 year old, came to Kiev from Berdichev, his aunt, a retired actress, took him to the theatre. The story of the fallen angel shook the boy, and drew him into the world of theatre for life. After the show ended, the boy jumped over the chairs and shouted, “You’ll be the queen of the world!”

That promise was yet very far from fulfilment when he started to perform. At 15, Alexander and his friends put on a public show. For the sake of secrecy, the boys used assumed names, Korenblit selecting Tairov for himself (Son of the eagle, tair being Arabic for eagle).

His father encouraged him and believed in his brilliant career in the theatre, but made him promise to finish school and the university. The headmaster of the two-year primary school in Berdichev, Yakov Korenblit knew what he was talking about. Alexander enrolled in the law department of Kiev University in 1904, and married his cousin Olga the same year. But theatre was the hub of his life. Kiev, a city of theatres, presented great opportunities, and soon the amateur moved to the professional stage.

The revolution of 1905 and the pogroms of Jews in Kiev did not bypass Tairov, then the father of a newborn daughter. He was one of the organizers of a general strike in Kiev theatres: his gift of persuasion was already apparent. The police did not miss this, and student Korenblit soon landed in prison.

A visit by Vera Komissarzhevskaya to Kiev was an opportunity for Tairov and he used it in full. The great actress was gracious to the young actor and invited him to join her theatre. After one more spell in solitary confinement, Tairov moved to St. Petersburg, where he acted in Komissarzhevskaya’s theatre and studied law at St. Petersburg University. In the early 20th century, Russia’s capital offered a synthesis of the arts and sciences, adequacy and conformity that were after the young provincial’s heart.

In 1906, life in St. Petersburg was also full of disputes about Russia’s future and the possibilities of creating an ideal world. Dostoyevsky’s words about beauty that would save the world were an article of faith. That was Tairov’s milieu.

Realism, romanticism and beauty

The university was not only lectures. Tairov joined the circle of Social Democrats led by Lunacharsky. However, talk about the party content in art did not hold the ex-revolutionary for long. He already had a vague feeling that art cannot be controlled by any party or doctrine; soaring above them, it must urge everyone to its heights. But his friendship with Lunacharsky was to last throughout his life and often came to his aid.

It was in the same season that Meyerhold came to Komissarzhevskzya. He was already the most fashionable pro-Westerner. Tairov’s first appearance on the stage in the capital city was in the part of the Beggar in Meyerhold’s version of Maeterlinck’s Sister Beatrice.

However, Tairov and the director built up no rapport. Tairov recognized that, thanks to Meyerhold, a collision of opinions had come to the theatre. He was fully on Meyerhold’s side in his fight against “realism at all costs,” but he could not accept Meyerhold’s slogan of “beauty at all costs.” After the February Revolution, Tairov suggested to Meyerhold and N. Yevreyinov that they launch a joint leftist theatre in which each of them would work independently. Long discussions came to nothing. Tairov and Meyerhold jointly staged Paul Claudel’s The Exchange but the experiment was a failure.

Tairov played only three parts in Komissarzhevskaya’s theatre but the young actor was noticed. He got an offer from Pavel Gaideburov to join the Moveable Theatre not only as an actor but as a director as well.

Tairov played a multitude of parts during his three years in the Moveable Theatre. Though not tall, but exotically handsome, stately, with a noble voice, Tairov was a success in romantic roles.

He staged his first play, Hamlet, at 22. The birth of a new director was announced by the press. A reviewer noted with wonderment that the play did not have the stereotype rolling eyes and twisting arms.

Tairov followed that with Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya, which also did not pass unnoticed. Even the rehearsals provoked polemics. The rehearsals were accompanied by the music of Tchaikovsky and Chopin. It was the director’s way of helping the actors achieve spiritual union in their scenes.

The press was sarcastic: “Tairov aspires to be a little Meyerhold.” They were wrong. Tairov was looking for his own path. He had grandiose plans. But a scandal broke out in Yekaterinburg during a tour. During a performance of Ostrovsky’s The Tempest, there was no prompter. Tairov, in the part of Boris, forgot his lines. Usually very proper and soft, Tairov was now enraged. He could not stand negligence. The three days of investigation brought to light a long-simmering conflict. The Chamber Theatre had ideal discipline, Tairov would part with his favorite actor if he was late for a show, once he was close to firing Koonen for idle talk at a rehearsal.

Tairov did not share Gaideburov’s naturalistic illusions nor the chief’s moral and ethical standards. Tairov left the Moveable Theatre accompanied by five people. Airing of views continued in a theatre magazine. Gaideburov mentioned in passing that the given name of his opponent was Korenblit.

Soon Tairov had other reminders of his origins. A well-known entrepreneur invited him to the Russian Theatre in Riga, but the police banned the Jew from staying in the city. The conflict took two weeks to resolve. At a meeting with the theatre company, Tairov concluded his speech by saying, “Our joint work will be joyful. Sincerely, with all my heart, I ask for one thing from you: Love me and cherish me.”

On return to St. Petersburg, Tairov converted to Evangelic Lutheranism.

Russia was moving ever farther from the ideal. Theatre was taking a bigger place in Tairov’s life. Now he was more a director than an actor. In each of his new shows, the director’s imagination and his particular theatrical sense delighted the public and critics.

H. Hauptmann’s Flight of Gabriel Schilling caused a veritable storm in theatre circles. Now Tairov knew precisely what he wanted, knew how to do many things, and could not fail to see that the theatre was turning into a laboratory of depression and psychopathy and that a crisis was inevitable because of “a terrifying deterioration of actors’ skills.”

After long hesitation, Tairov graduated from the university (with honors) and gave up the theatre.

At the age of 27, Tairov moved to Moscow and joined a corporation of advocates. A brilliant career in law was foretold for him. But again theatre seduced him, this time forever. He met like-minded people and his queen. The disciple and hope of the Arts Theatre, the object of adoration of Kachalov, Andreyev and Skriabin, Alisa Koonen preferred the married and balding demon of staging. Unlikely as it seemed, they had in common an all-absorbing love of art, a faultless sense of beauty and a thirst for adventure.

He created a theatre for her, one he had dreamed of: intellectual, intimate, and winningly cheerful. The actress brought the irrationality of passions, intonations and gestures to the director’s mathematically rigorous stagings.

The chamber people and the volunteers

Tairov’s first staging was Sakuntala by the ancient Indian poet Kalidasa. His brainchild was a synthetic theatre of lofty feelings and lively expressiveness. The sentimental and wise love story was joyful, impeccably beautiful and erotic. It became Tairov’s programme piece. At the close of his days, as he reviewed his life, he would write that love had always been his principal theme, love and sacrifice, love and heroism, love and patriotism, love and art. Love was alive in the lofty sadness of Phaedra, in the carefree playfulness of Girafle-Girafla and the joyful phantasmagoria of Princess Brambilla, the all-absorbing sentiment of Adrienne Lecouvrer, the manliness of The Optimistic Tragedy, and the bitterness of Madame Bovary. The brilliance of the show and the depth of feeling amazed audiences in Moscow, Paris, Khabarovsk, Buenos Aires, Berlin and Kronstadt.

Besides his energy and artistic talent, Tairov invested practicality and brilliant management in his theatre. The moulder of the scene, as the artist described himself, became a moulder of the theatre business.

His theatre had a studio, in which Tairov formed actors full of optimism, sculptural expressiveness and inner richness. In the critics’ opinion, the graduates of his school had the sacred right to forget elements of their art. The studio produced many interesting actors, among them Evgeny Lebedev.

The theatre published a newspaper of its own, books, arranged exhibitions, talks, lectures and concerts. Every night, Tairov went out to greet the audience, to thank the spectators for visiting and to say that the show would be an artistic and aesthetic pleasure.

The theatre’s climate of ideal co-creativeness surprised contemporaries. For a long time, the theatre knew no squabbles or plots, the people served for years, and welcomed the director’s appearance at rehearsals with applause.

Tairov was the first in Russia to stage several plays of O’Neal and Brecht’s Three-Penny Opera, J.-B. Priestly’s work was on in Moscow even before London.

Balmont and Bryussov worked with the theatre. The theatre artists were P. Kuznetsov, A. Ekster, A. Vesnin, N. Goncharova,

M. Larionov, S. Sudeikin and G. Yakulov.

The leader of the orchestra was A. Alexandrov, the future creator of the famous Song and Dance Ensemble of the Soviet Army. Music of Prokofiev, Sviridov and Kabalevsky accompanied the theatre’s plays. Tairov invited Faina Ranevskaya from the province; M. Zharov performed one of his best parts in The Optimistic Tragedy. The Chamber Theatre’s overseas tours of Europe and South America in 1923 and 1930 were “a total victory of the famous Russian innovator and a genius of staging The theatre tours were reported on even in the places it did not visit. A critic in Paris stated, “Tairov’s company deserves the brilliant international fame that it enjoys.”

The fatal island

But even in its hour of triumph, the Chamber Theatre was in the focus of interminable controversies. Tairov remained aesthetic, that is, bourgeois and, consequently, alien.

But Tairov did not betray his views, and fought for his own opinion to the end of his days.

The Soviet power gave the Chamber Theatre the status of a government theatre and provided it with material well-being, and its director was sincere in his vain attempts to keep in step with those who were marching on to communism.

In 1927, at a dress rehearsal of

The Conspiracy of Equals, there was applause for Babeuf’s monologue after he was sentenced to die by the Directoire. Babeuf was Trotsky/Tairov. The author of the play was charged with Trotskyism, and the play was banned.

In 1929, the director produced Bulgakov’s The Crimson Island, which was fatal for him. He always admired theatre miracles and knew how to create them. The play ridiculed the absurdity of scenic propaganda. Stalin labelled the play bourgeois, which was sufficient for hounding Tairov. But, on that occasion, the actors stood up for him.

The decadent love

Natalia Tarpova appeared as a response to The Crimson Island, a timely prediction of the impending epoch of the round-the-clock mobilization. The OGPU (a forerunner of the KGB) found the un-Party love of a woman Party member decadent.

The time of extravagance and daring was past, the word “understandability” was coming into vogue, and the ordinary man made his entry to the boards.

At last, Tairov found a play that marked a turning point in the history of the theatre. Tairov admited that “had he not been poisoned by the theatre from his green years, he would surely have become a seaman.” Therefore, the director worked enthusiastically with Vishnevsky’s The Optimistic Tragedy, despite Gorky’s criticism of the play. Meyerhold, too, rejected it. Tairov took the author on a visit to the Baltic Navy and, in fact, re-wrote the play. The play astounded everybody. True, the scene of the Commissar’s meeting with Alexei was dropped, but The Optimistic Tragedy is in all the textbooks on modern theatre.

Inspired by the long-awaited success, the Chamber Theatre chief following the tradition went on to lighter stuff, Borodin’s forgotten joke play The Warriors. Theatre administrators suggested D.Bedny as the author of the libretto. The text turned out rather coarse but the show was splendid, the first reviews ecstatic. The fifth or sixth show was visited by Molotov. The sentence was announced after Act One: a slander of Russian history.

The year was 1936. Very few enthusiasts were willing to defend Tairov. The director repented but was stubborn in his belief that the theatre must be synthetic. He went even farther when he called for putting theatres on the level of research institutes. “Pavlov has an institute on which millions are spent. Stanislavsky must have an institute, too.”

As a punishment, the Chamber Theatre was joined to Okhlopkov’s Realistic Theatre and later sent on a year’s tour of Siberia and Far East. But the theatre survived. In 1940, its legendary Madame Bovary appeared, the story of love profaned.

The stick would replace the carrot, on jubilee days the “bourgeois director” would be graciously awarded and given a chance to work. In 1949, the theatre was taken from him.

It all started in 1946 with the Party resolution “On the Repertoire of Drama Theatres and Means of their Improvement.” A new expression was coined servility to the West. The Resolution noted, in part, that, out of the eleven plays shown by the Chamber Theatre, only three were about contemporary Soviet life.

Tairov’s response was Gorky’s The Old Man. He invited Gaideburov from the provinces to play the leading part. The show was a tremendous success, there was even talk of a Stalin Prize. Nothing of the kind. Tairov did not give up. He started reworking Phaedra, preparing a pantomime to the music of Beethoven and Tchaikovsky, negotiated with Pasternak and Bergholtz, planned to stage the first play of the young talented Galich The Start of the Road, and even wrote an enthusiastic article about “the talented and exacting artist,” although his play was termed an “ersatz” and its author “a greenhorn.”

Tairov was desperately looking for a way out, but time was against him. Koonen was approaching 60 and her performances were already erratic. Gone were his great opponents with whom his disputes had brought truth, each its own, and with whom he could join ranks in the face of real danger. He was alone now. Debates were replaced by hand-to-hand combat. Hoping to save the Chamber Theatre, Tairov offered the young director Tovstonogov to be its head, stipulating for himself the staging of one play a season. Tovstonogov did not accept the offer.

In 1948, Mikhoels died, and the case of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee began.

In December 1948, a plenary session of the Writers’ Union considered Soviet dramatic art after a resolution on its repertory. A new guilty party was found: the theatre critics. There were discussions on a “levelling” of theatres, and the opinion was voiced that Tairov had lost his individuality. At the last general meeting of the company in the spring of 1949, the actors failed to take into consideration the age or nature of the founder of the theatre as they discussed his performance; Gaideburov in particular hit to kill.

Tairov submitted his resignation.

A bathroom in place of the office

The Committee for Arts’ order 408 of May 1949 noted the unsatisfactory situation in the creative work of the Chamber Theatre: “Being unable to overcome his earlier mistakes, the art director’s practical work has brought the theatre into a situation where it has not acquired a new creative image and has failed to take the road to becoming a realistic theatre.”

On May 29 was the 816th performance of Adrienne Lecouvrer, the last performance in the history of the Chamber Theatre. The actors’ performance was not smooth. Koonen was an exception: her performance was admirable. The Chamber Theatre did not last a few months to its 35th anniversary.

After the Chamber Theatre was destroyed, Tairov was permitted to be on the payroll of another theatre, was granted a personal pension, and given official thanks for “many years of creative work for the progress of Soviet theatre art.” The artist did not last long after the demise of his creation. His mind could not stand it. Alexander Yakovlevich Tairov died of brain cancer on September 5, 1950, in Solovievskaya Psychiatric Hospital. His last words were “Alisa, Alisa.” (the first name of Koonen).

He was buried in Novodevichye Cemetery. At his interment, Y. Zavadsky read reproaches against him for his “errors.”

The A.S. Pushkin Theatre took the place of the Chamber Theatre at 23 Tverskoy Boulevard. The building was repaired, and Tairov’s office was converted into a men’s lavatory.

In her will, written

on a piece of paper torn out of a school copybook, Alisa Koonen mentioned a

museum and added “…take the trouble.” There was nobody to

take the trouble. Tairov had no followers. His time has not yet come.

ABRAHAM FIRKOVITCH

|

Abraham (Avraham) Firkovitch (1786-1874) was a Lithuanian Karaite of Crimean Karaite (Karaim) descent, born in Lutsk, Volhynia. Firkovitch was a communal leader and hakham. He is best known as a collector of manuscripts and amateur archeologist. |

Abraham Firkovitch, date unknown. From the 1901-1906 Jewish Encyclopedia.In 1818 he was hazzan of his native city, an office which among both Karaites and Rabbinites includes that of cantor, reader, teacher, and minister. In 1828 he lived in Berdichev, and had controversies with some Rabbinite Jews, the result being his anti-rabbinical work Masah u-Meribah (Eupatoria, 1838). In later years when he became closely connected with the Rabbinites, he repudiated the sentiments contained in that pamphlet. In 1830 he visited Jerusalem, where he collected many Karaite and Rabbinite manuscripts. On his return he remained two years in Constantinople, as teacher in the Karaite community.

He then went to the Crimea and organized a society to publish old Karaite works, of which several appeared in Eupatoria (Koslov) with comments by him. In 1838 he was the teacher of the children of Simchah Babovich, the head of the Russian Karaites, who one year later recommended him to Count Vorontzov and to the Historical Society of Odessa as a suitable man to send to collect material for the history of the Karaites. In 1839 Firkovich began excavations in the ancient cemetery of Chufut-Kale, and unearthed many old tombstones, some of which, he claimed, belonged to the first centuries of the common era. The following two years were spent in travels through the Caucasus, where he ransacked the genizot of the old Jewish communities and collected many valuable manuscripts. He went as far as Derbent, and returned in 1842. In later years he made other journeys of the same nature, visiting Egypt and other countries.

In Odessa he became the friend of Bezalel Stern and of Simchah Pinsker, and while residing in Wilna he made the acquaintance of Fuenn and other Hebrew scholars. In 1871 he visited the small Karaite community in Halicz, Galicia, where he introduced several reforms. From there he went to Vienna, where he was introduced to Count Beust and also made the acquaintance of Adolph Jellinek. He returned to pass his last days in Chufut-Kale, of which there now remained only a few ruins.

Firkovitch collected a vast number of Hebrew, Arabic and Samaritan manuscripts during his many travels. These included thousands of Karaite and rabbinic documents from throughout the Russian Empire in what became known as the First Firkovitch Collection. He was one of the first to visit the Cairo Genizah with the intention of cataloging and studying its contents. His visit, in 1863, took place thirty four years before Solomon Schechter's more famous trip; Firkovitch therefore got first pick of the documents contained in the Genizah. Though this "Second Firkovitch Collection" contains only 13,700 items in comparison to Schechter's 140,000, the Firkovitch documents are generally more complete.

In his later years he became obsessed with "proving" that the Karaites of Russia were not Judean in descent, but rather Khazarian; to this end Firkovitch resorted to forgeries of tombstones and documents. Because of this, and his secrecy regarding the sources for the Second Collection, any document that passed through Firkovitch's hands is academically suspect. His theories, though historically implausible, caught on in the Russian imperial court, and the Karaites were excluded from the restrictive measures against other Jews.

Upon his death in 1874 Firkovitch's collection was bought by the Russian National Library.

Among the treasures in the Firkovitch collection is a manuscript of the Garden of Metaphors, an aesthetic appreciation of Biblical literature written in Judeao-Arabic by one of the greatest of the Sephardi poets, Moses ibn Ezra.

ISRAEL GRODNER

Israel (Yisrol) Grodner (ca. 1848–1887) was one of the founding performers in Yiddish theater. A Lithuanian Jew who moved at the age of 16 to Berdichev, Ukraine, the Broder singer and actor was in Iasi, Romania in 1876 when Abraham Goldfaden recruited him as the first actor for what became the first professional Yiddish theater troupe. Jacob Adler remarks that as the only Lithuanian Jew in the early years of Yiddish theater, he deliberately spoke a different dialect of Yiddish on stage so that it would blend better with the other actors. (The Yiddish of Lithuania differed from that of Ukraine and Romania.)

Although his early performances with Goldfaden are usually considered the start of professional Yiddish-language theater, as a Broder singer Grodner was already something of an actor, and he had already participated in an 1873 concert in Odessa, Ukraine in which he and other Broder singers sang songs (including some of Goldfaden's) and improvised comic material between songs that was very similar to Goldfaden's early, highly improvised, comic musical plays. Actor Jacob Adler, already a big fan of the highly regarded Russian language theater in Odessa at that time, and who saw Grodner perform in taverns and restaurants, indicates in his memoir the strong impression Grodner made on him for how well he portrayed his characters. Lulla Rosenfeld writes that Grodner was known in Odessa as "Srolikl Papirosnik" (from papiros, cigarette) because he always had a cigarette dangling from his lip.

Grodner met his wife Annetta in his travels as a Broder singer. She was also a fine performer, and eventually had a career of her own in Yiddish theater.

Grodner joined Goldfaden in the performances at the legendary Gradina Pomul Verde ("Green Fruit-Tree Garden") in Iasi, then, when they could not rent a theater building in Iasi, traveled with him to perform in Botosani, Galati, Braila, and finally Bucharest, where the troupe became an enormous hit, but where Grodner began to be eclipsed as lead actor by Sigmund Mogulesko.

Grodner quit Goldfaden's company to found his own in Iasi, taking with him Moishe Finkel, Rosa Friedman, and his own wife, who was a good singer but had not previously been a stage performer; Sokher Goldstein soon followed. He recruited Joseph Lateiner as a playwright; their first play was The Two Schmul Schmelkes, based on a German story "Nathan Schlemiehl".

Soon Mogulesko also quit Goldfaden's company and joined Grodner's. In 1880 Grodner and Mogulesko toured to Warsaw, but soon Mogulesko had taken over the troupe and once again supplanted Grodner; Jacob Adler reports that around this time he also toured to Constantinople, briefly rejoined Goldfaden in Odessa, and then temporarily joined the traveling troupe of Israel Rosenberg, but that he was already in declining health at this time.

Shortly before Grodner founded a new troupe in Riga (again with Finkel, Friedman, and his wife Annetta, now their prima donna); after the 1883 ban on Yiddish theater in Imperial Russia, they went to London (which was briefly the center of Yiddish theater). The Grodners were briefly in a London troupe with Jacob and Sonya Adler at London's Prescott Street Club, at the first performance of which they played the leads in Der Bel Tchuve (The Penitent) by N.M. Sheikevitch; he also played the mischievous Tzingatan in a production of Goldfaden's Shulamith. Grodner soon left to found yet another troupe in Galicia, with which he toured to Vienna. His travels continued: London, Warsaw, and then back to London, where he died in 1887. According to Bercovici, he was buried in an unmarked grave in "Stratford"; it is not clear whether this means Stratford-upon-Avon or Stratford, London.

RABBI YEHUDA-LEIB SHALITA

(informed by Kriss Foundation)

The Shalita family branch lived in Berdichev, Ukraine for generations.

Rabbi Yehuda-Leib Shalita, probably born in Berdichev circa 1795, came from a long paternal line of religious leaders linked back to Rashi, the prominent medieval philosopher. A Berdichev synagogue survives to this day.

Moshe Shalita, born circa 1845, immigrated to the U.S. at the turn of the century, along with his immediate family.

TATIANA YELINA MCWETHY

Tatiana McWethy, born in the Ukraine town of Berditchev, has resided (with her husband Ian) in Sonoma since 2006. She is a 1986 graduate of the Zheleznogorsky Art College in Russia, having previously attended The Berditchev School of Art. A professional Artist since 1987, Tatiana also worked doing restorations and iconography for churches; her icons are in the collections of a number of St Petersburg churches, including the Church of the Annunciation and the Chapel of St Olga. In addition to a solo exhibition in the Palace Kotchubey in 1996, Tatiana also participated in the Portrait exhibition in the Art Academy in St Petersburg. Her paintings hang in private collections in Russia and Europe as well as in the United States.

Tatiana, a student of the Art College of Russia since the age of 14, found her niche in restoring classic works of art. She worked under Sergey Kisilev, leading restoration artist for the world famous Hermitage Museum.

Tatiana excelled at restoring religious icons from Russian Orthodox churches all across the country. Eventually, she became a restoration artist of the Peter and Paul Fortress, which includes the Peter and Paul Cathedral where all of Russia’s emperors and empresses have been buried, from Peter the Great to Alexander III.

In her spare time, McWethy still pursued her own artwork.

She uses rich colors to create portraits, still-life and landscapes in the traditional European style.

SAMSON KRUPNICK (1913-2009)

(Courtesy:Israel Net Daily Editor in Chief)

Samson Krupnick, author of the column "Israel as I See It" for the past 45 years, passed away this week at the age of 96. Probably among the longest-running columns in journalism, this column has been a piece of history, faithfully recording the important events, the wars, the peace accords, the development of the country and its institutions, the ongoing, everyday happenings, as well as an overall picture of the State of Israel, its people, its values, its Jewish content and its flourishing enhancement over time, from a young, struggling state to a country of successful achievements. The author depicted problems as well as attainments, the almost impossible maze of the Middle East and the deadlock of conflict between Israel and its Arab neighbors, which has, thus far, defied all attempts towards finding lasting and far-reaching solutions.

What may not have come across in the decades of these columns is Samson Krupnick's own achievements and very unique and tremendous contribution to the world around him. His 96 years, as portrayed in a book he wrote a few years before his passing, reflected much of the history of the Jewish people and the stormy events of the past century. Born in Berdichev, and seventh generation descendant of Rabbi Levi Yitzhak of Berdichev, he survived two pogroms as a child, and had to escape from the Ukraine under cover of night and under gunfire, because his father was the head of the Zionist Organization of Berdichev. Their aspiration was to move to Israel immediately, but relatives there made it clear that the family would not be allowed to enter the country without a job, and that jobs were not available.

The family made their way to Poland, to Canada and to Chicago remaining staunch supporters of Zionism all the while. The family became a part of the growing Jewish community of Chicago. After the tough years of the depression, Samson Krupnick became involved in developing all the components that constitute a strong Jewish community the synagogues, Jewish education, school systems on every level, cultural and community activity, work on behalf of individuals who needed assistance and Zionist activity. He devoted his days to work and every night to meetings on behalf of Jewish causes and the needs of the community. During the following decades, the Chicago Jewish community developed and advanced, his leadership touching virtually every sphere of activity. Active in the Mizrachi movement, he was eventually elected co-Chairman of the Mizrachi Hapoel Hamizrachi of North America. The celebrations of the establishment of the State of Israel and of the subsequent Independence Days were massive events in the Chicago Stadium and a tradition of solid support for the State was maintained.

Samson Krupnick eventually fulfilled his dream of making aliya to Israel with his family. In August, 1965, he went into semi-retirement to move to Israel, with his son-in-law, a partner in the Chicago accounting office, taking over the ongoing activity of the office. He devoted the remainder of his life to the advancement of Israeli institutions and important causes. He was Chairman of the Board of Shaare Zedek Hospital for ten years and on the Boards of Bar Ilan University, Mossad Harak Kook, Kerem B'Yavneh and countless other yeshivas and institutions of learning and culture. He chaired dinners and fundraising projects for over 250 institutions and for scholarships and other help for the many who required assistance all on a volunteer basis. He invested all his energies in teaching institutions to help themselves. His extraordinary leadership in a broad spectrum of spheres earned him the Yakir Yerushalayim - Jerusalem Award and dozens of other awards.

His grandson, at age 12, took an entrance exam to a yeshiva high school, and was asked to write on a form what his father and mother and grandfather do. After some thought, he wrote that his grandfather is a Chairman. True, he was always the chairman, always in charge, always spearheading the efforts necessary to create, improve, build, develop and advance. And under his leadership, thousands of others were faithful partners in these good works and making a difference. His 96 years were rich with dynamic action and varied forms of energetic endeavor. He played tennis until two months before his passing, and only stopped because of the weather. Four years ago he competed in the international Maccabiah (in the senior group of tennis players) as the oldest competitor in the competitions and won a gold medal.

He is survived by his wife, Rose, five children, 16 grandchildren and 49 great grandchildren (with one more on the way). In the hospital, the family held a birthday party in his honor, attended by over 70 family members, whom he blessed with every success, enjoying the nahat of a patriarch, who could take pride in his loving family.As his family sat shiva in their home in Jerusalem, hundreds of people paid their respects, many saying that he had influenced and changed their lives, many others saying that he was the most exceptional person they have ever had the honor of meeting and knowing and many others saying that they had worked with him on this or that project and that he was amazing. He touched the lives of hundreds of thousands and made them better, always giving of himself, never saying "no" to anyone. While this is the end of an era, the impact of his lifetime of dedication to humanity will live on for generations after him, and his heritage will be cherished by many.

MOYSHE NOTOVICH

Born in 1912, Berdichev- passed away in1968, Kazan) was an Yiddish writer and literary critic distinguished for his research on the Yiddish poet and playwright Yitzkhok Yoyel Linetsky (1839- 1915). He taught Yiddish literature at the studio school of the Yiddish GOSET Theater and contributed to the Yiddish periodicals Eynikayt, Heymland, and Sovetish heymland. After the suppression of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, Notovich was forced to move to Kazan, in the remote Soviet republic of Tatarstan, where he taught Russian literature at a local university. In 1983, his only book, Kritike un kritikers (Critic and Critics), was published as a supplement to the Yiddishjournal Sovetish heymland.

SAMSON KRUPNICK (1913–2009)

Samson Krupnick, author of the column “Israel as I See It” for the past 45 years, died this week at the age of 96. Probably among the longest-running columns in journalism, this column has been a piece of history, faithfully recording the important events, the wars, the peace accords, the development of the country and its institutions, the ongoing everyday happenings, as well as an overall picture of the State of Israel, its people, its values, its Jewish content and its flourishing enhancement over time, from a young, struggling state to a country of successful achievements. Krupnick depicted problems as well as attainments, the almost impossible maze of the Middle East and the deadlock of conflict between Israel and its Arab neighbors, which has, thus far, defied all attempts toward finding lasting and far-reaching solutions.

What may not have come across in the decades of these columns is Samson Krupnick’s own achievements and very unique and tremendous contributions to the world around him. His 96 years, as portrayed in a book he wrote a few years before his passing, reflected much of the history of the Jewish people and the stormy events of the past century. Born in Berdichev, and a seventh generation descendant of Rabbi Levi Yitzhak of Berdichev, he survived two pogroms as a child and escaped from the Ukraine under cover of night and under gunfire because his father was the head of the Zionist Organization of Berdichev. Their aspiration was to move to Israel immediately, but relatives there made it clear that the family would not be allowed to enter the country without a job, and that jobs were not available.

The family made their way to Poland, to Canada and to Chicago – remaining staunch supporters of Zionism all the while. The family became a part of the growing Jewish community of Chicago. After the tough years of the depression, Samson Krupnick became involved in developing all the components that constitute a strong Jewish community – the synagogues, Jewish education, school systems on every level, cultural and community activity, work on behalf of individuals who needed assistance and Zionist activity.

He devoted his days to work and every night to meetings on behalf of Jewish causes and the needs of the community. During the following decades, the Chicago Jewish community developed and advanced, his leadership touching virtually every sphere of activity. Active in the Mizrachi movement, he was eventually elected cochairman of the Mizrachi Hapoel Hamizrachi of North America. The celebrations of the establishment of the State of Israel and of the subsequent Independence Days were massive events in the Chicago Stadium and a tradition of solid support for the State of Israel was maintained.

Samson Krupnick eventually fulfilled his dream of making aliya to Israel with his family. In August, 1965, he went into semi-retirement to move to Israel, with his son-in-law, a partner in their Chicago accounting office, taking over the ongoing activity of the office. He devoted the remainder of his life to the advancement of Israeli institutions and important causes.

He was chairman of the board of Shaare Zedek Hospital for ten years and on the Boards of Directors of Bar Ilan University, Mossad Harak Kook, Kerem B’Yavneh and countless other yeshivas and institutions of learning and culture. He chaired dinners and fundraising projects for over 250 institutions and for scholarships and provided other help for the many who required assistance – all on a volunteer basis. He invested all his energies in teaching institutions to help themselves. His extraordinary leadership in a broad spectrum of spheres earned him the Yakir Yerushalayim – Jerusalem Award and dozens of other awards.

His grandson, at age 12, took an entrance exam to a yeshiva high school and was asked to write on a form what his father and mother and grandfather do. After some thought, he wrote that his grandfather is a “Chairman.” True, he was always the chairman, always in charge, always spearheading the efforts necessary to create, improve, build, develop and advance. And under his leadership, thousands of others were faithful partners in these good works and making a difference.

His 96 years were rich with dynamic action and varied forms of energetic endeavor. He played tennis until two months before his passing, and only stopped because of the weather. Four years ago he competed in the international World Maccabiah Games (in the senior division of tennis players) as the oldest competitor in the competitions and won a gold medal.

He is survived by his wife, Rose, five children, 16 grandchildren and 49 great-grandchildren (with one more on the way). In the hospital, the family held a birthday party in his honor, attended by over 70 family members, whom he blessed with every success, enjoying the nahat of a patriarch, who could take pride in his loving family.

As his family sat shiva in their home in Jerusalem, hundreds of people paid their respects, many saying that he had influenced and changed their lives, many others saying that he was the most exceptional person they have ever had the honor of meeting and knowing and many others saying that they had worked with him on this or that project and that he was amazing. He touched the lives of hundreds of thousands and made them better, always giving of himself, never saying no to anyone. While this is the end of an era, the impact of his lifetime of dedication to humanity will live on for generations, and his heritage will be cherished by many.

The family: Rose Krupnick, Prof. Joseph Kedem, Deborah Bokor, Rabbi Eliahu Krupnick, Elissa Allerhand and Rachel Lieberman

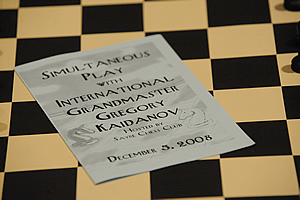

GREGORY KAIDANOV

( born October 11, 1959) is a Grandmaster of chess.

|

|

|

|

He was born in Berdychiv, Ukrainian SSR, but in 1960 first moved to Kaliningrad, Russian SFSR. He learned to play when he was 6 years old from his father. At age 8, he started to attend a chess study group in 'Pioneer's House.' As an adult, he moved to Lexington, Kentucky in 1991, with his two children and wife.

He won the 1992 World Open in Philadelphia, and the 1992 U.S Open.

His first major tournament win came in Moscow 1987, where he defeated Indian star Vishwanathan Anand. He earned the IM title that same year, and was awarded the GM title just a year later in 1988.

He is the head coach of the www.uschessschool.com founded in 2006 by IM Greg Shahade.

Highlights of his chess career:

1972 - Boys under-14 Russian Federation Championship - 1st place

1975 - Became a Candidate of Master (analog of expert in US)

1978 - Became a Master

1987 - Became an International Master

1988 - Became a Grandmaster

1992 - Won World Open Chess Championship

1992 - Won U.S. Open Chess Championship

1993 - Won World Team Chess Championship as a member of US team

1998 - Silver medal in Chess Olympiad as a member of US team

2001 - Won North American Open Chess Championship

2002 - Won Aeroflot Open (one of the strongest open tournaments of all times, with 82 grandmasters participating)

2008 - Won the Gausdal Classic, held April 8th-16th in Gausdal, Norway, scoring 7/9.

VALERIY SERGEYEVICH SKVORTSOV

Valeriy Sergeyevich Skvortsov (Russian: Валерий Скворцов), (b. May 31 1945, Berdychiv, Ukraine, former USSR) is a former high jumper who represented the USSR in the 1964 and 1968 Summer Olympics.

Skvortsov was first noticed by Soviet high jump coach Viktor Lonsky, who offered him training in a converted sports gym located within the walls of an old Catholic cathedral. His sports career began to accelerate as he won various local high jump competitions and later was invited to Moscow to train for the Soviet Olympic team.

Skvortsov had subsequently participated in the Tokyo Olympic Games of 1964, where he took the 14th place in the high-jump final with a jump height of 2.06 meters. Valeriy Brumel from the Soviet Union), and John Thomas from the United States won the gold and silver medals, respectively.

At the 1966 European Indoor Games championship in Dortmund, West Germany, Skvortsov won first place with a career best jump of 2.17 meters. At the 1968 European Indoor Games he successfully defended his title as the European high jump champion winning first place again with 2.17 meters.

Skvortsov participated in the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico city, where he competed with Dick Fosbury and Valentin Gavrilov. His 2.16 meter jump secured him a fourth place finish.

After a leg injury forced him to stop competing, Skortsov continued as a high jump trainer in Moscow (Dinamo) and then went to work as the head of Duma security. Skvortsov is currently retired and resides in Moscow, Russia.

RAV MOSHE MEIR ROSENSTEIN

Rav Moshe Meir Rosenstein of Berditchev (1821-1902). A student of the Rizhuner Rebbe in his youth, Rav Moshe Meir moved to Eretz Yisral and settled in Tzefas in 1853, living there for several decades. At the end of his life, he settled in Teveria. His insights have been published recently in a sefer called Avodas HaLevi’im.

GREGORY S. NUSINOVICH Senior Research Scientist

Gregory Nusinovich was born in 1946 in Berdichev, former Soviet Union. He received the B.S. and Ph.D. degrees from Gorky State University in 1968 and 1975, respectively.

After graduating from Gorky University he joined the Gorky Radiophysical Research Institute. From 1977 to 1990 he was a research scientist and head of the research group at the Institute of Applied Physics of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. From 1968 to 1990 his scientific interests were aimed at developing high power millimeter and submillimeter-wave gyrotrons. He was also a member of the Scientific Council on Physical Electronics of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR.

In 1991 he immigrated to the USA, where he joined the research staff at the Institute for Research in Electronics and Applied Physics, University of Maryland. His current research interests include the study of high power electromagnetic radiation from various types of microwave sources. Since 1991 he has also served as a consultant to the Science Applications International Corporation, the Physical Sciences Corporation, and Omega-P.

Dr. Nusinovich is the author of the book "Introduction to the Physics of Gyrotrons," published by The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004. It is included in the series, Johns Hopkins Studies in Applied Physics.

Dr. Nusinovich is a Fellow of both the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers and the American Physical Society.

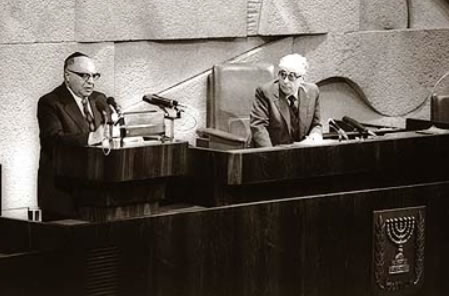

YOSEF TAMIR

Tamir was born in Berdychiv in the Russian Empire (now part of Ukraine) and immigrated to Mandate Palestine in 1924. He passed through elementary and high school in Petah Tikva and graduated from the Law and Economics School at Tel Aviv University.

Between 1935 and 1945 he worked as a journalist for Haaretz, the Palestine Post, Yedioth Ahronoth, Maariv and HaBoker, and was a military correspondent during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. He was a member of the Maccabi Sports Movement, and won three medals in the Maccabiah Games.

Political career:

Tamir joined the General Zionists party, and became its general secretary. Between 1965 and 1969 he was a member of the Tel Aviv directorate as head of the Liberal Party faction (a merger of the General Zionists and the Progressive Party). In the 1965 elections Tamir was also elected to the Knesset as member of Gahal, an alliance of the Liberal Party and Herut. Yosef retained his seat in the 1969 election, and again in the 1973 election, before which Gahal had become Likud.

After being elected to the Knesset for Likud again in the 1977 election, Tamir broke away from the party and joined the newly-formed Shinui, a centrist liberal party. However, he soon left his new party and spent the rest of the Knesset session as an independent MK. He was not returned to the Knesset in the 1981 elections.

YITZHAK BERMAN

Born in Berdychiv in the Russian Empire (today in Ukraine), Berman made aliyah to Mandate Palestine in 1920. He studied at a teacher training college in Jerusalem, before studying to be a lawyer in London.

In 1939 he joined the Irgun and worked in the organisation's intelligence department. In 1941, during World War II, he enlisted in the British Army and served in intellgience. He also served in the Israel Defense Forces between 1948 and 1950, fighting in the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.

In 1950 he began work as the legal advisor of the Kaiser-Fraizier Factory in Haifa, becoming Director General by the time he left in 1954. In 1951 he joined the General Zionists and became chairman of the party's Tel Aviv branch in 1964. In 1974 he became chairman of the party's national secretariat, and in 1977 elections was voted into the Knesset on the list of Likud (of which the General Zionists had become a faction). After being re-elected in 1981 he was appointed Minister of Energy and Infrastructure in Menachem Begin's government. However, he resigned from the post on 30 September 1982 due to the government's attitude towards the Kahan Commission, which was investigating the Sabra and Shatila massacre.

Berman lost his seat in the 1984 elections. In 1986 he was amongst the founders of the Centre Liberal Party, and the following year was one of the founders of the Centre Party (unrelated to the later Centre Party).

RAQUEL LIBERMAN (RUJLA LAJA LIBERMAN)

(Courtesy: Nora Glickman)

Raquel Liberman was born in Berdichev in the Ukraine on July 10, 1900. As a child, she emigrated with her family to Warsaw. On December 21, 1919 she married Yaacov Ferber, a tailor, in Warsaw, according to the Jewish rite. In l920 their first son, Joshua David Ferber, was born. A year later, while she was pregnant with her second child, Yaacov Ferber emigrated to Argentina alone, joining his married sister and brother-in-law in the small village of Tapalqué, in the province of Buenos Aires. By the time Raquel Ferber and her sons Joshua and Moshe Velvele (Mauricio) joined him in Buenos Aires on October 22, 1922, Yaacov was already suffering from tuberculosis. He died a few months later. In order to support her family and with no knowledge of Spanish, Raquel, aged twenty-three, found herself obliged to leave her children in her provincial village, under the care of trusted neighbors, and find work in the capital. Unable to makes ends meet from her work as a seamstress, she was either forced into or voluntarily entered prostitution. Facts and fiction about her actual dealings are blurred. What is undisputed, however, is that after a few years of practicing that trade, she tried unsuccessfully to leave it. After a second attempt she succeeded in publicly denouncing the Zwi Migdal, formerly called Varsovia, a Jewish organization named after its founder, Zwi Migdal, which engaged in the white slave trade.

A close examination of Raquel Liberman’s recently discovered personal letters, photos and documents gives clear proof that she told the public only part of the truth about herself, deliberately choosing to keep her life from 1924 to 1928 in obscurity. She succeeded in concealing her legal marriage in Poland and the birth of her children from both the Zwi Migdal and the police. In her 1929 declaration she stated that her identity card indicated that her marital status when she immigrated to Buenos Aires in 1924 was that of a single woman. She also stated that she had been forced into prostitution and that she had been accompanied by a certain Bronya Coyman. Coyman turned out to be the traffickers’ agent who led her to her first exploiter, Jaime Cissinger. Furthermore, Raquel Liberman stated that after working for four years as a prostitute she managed to pay for her freedom and that, although she opened an antique shop and became independent, she continued to suffer pressure from the traffickers.

Unlike other victims of exploitation, Raquel Liberman was allowed to pay her “caftan,” Jaime Cissinger, a percentage of her earnings in exchange for his protection. But she managed to put away enough money to buy her own freedom and arranged for her rescue with the help of a compatriot. With her savings she opened an antique shop in Buenos Aires. But when the organization realized her ruse, they sent an intermediary, Mauricio Kirstein, to force her back with physical threats. At this point Liberman issued her first denunciation to the police, on December 29, 1929. As the first ploy of the Zwi Migdal had failed, they lured her with a marriage proposal. Liberman fell for it, and married José Salomón Korn in a Jewish ceremony, ignorant of the fact that the synagogue at 3280 Cordoba Street was false and the ten witnesses at the wedding all members of the Zwi Migdal, so that her marriage was a farce. The honeymoon turned out to be very short, since she soon realized that she had been deceived and that her new husband was a notorious pimp. Besides taking away her belongings, Korn forced his “wife” to resettle in another brothel in Buenos Aires. Looking for help, Raquel approached Simon Brutkievich to intercede in her favor, not knowing that he was president of the Zwi Migdal. Brutkievich proposed compensating her by returning part of her stolen money and jewels on condition that she cancel her denunciation to the police. But rather than give in, Liberman stayed firm in her action.

Having failed in her attempts to gain her freedom and dispossessed of all her belongings, Liberman once again became a victim of the traffickers. In order that she not lose her authorization to return to prostitution, the procurers’ syndicate sent her papers to the court, declaring that Liberman was living a double life, “given to prostitution in her country of origin, and that she continued practicing it professionally since her arrival in Buenos Aires without interrupting the obligatory visits to the Municipal Health Office when she set up her business.”

| Raquel Liberman with her sons |

On December 31, l929, after her failure to recover her money from the Zwi Migdal, Liberman sought the help of Ezrat Nashim, the Society for the Protection of Girls and Women. She endured further slavery before managing to submit another denunciation to Chief Police Inspector Julio Alsogaray, who was investigating the Zwi Migdal for crimes of corruption, extortion and blackmail and had been attempting for years to act against this criminal organization. For their part, to purge the “impure” elements (the “teme’im”) from their midst, the Jewish institutions openly confronted the traffickers. The campaign they mounted against them consisted mostly of expelling them from their community, preventing them from entering their synagogues and from burying their dead in Jewish cemeteries.

In 1930, when the civil government of Hypólito Yrigoyen (1852–1933) fell as a result of the military coup d’état of General Uriburu, the time was ripe for a judge, Manuel Rodriguez Ocampo, to raid the headquarters of the Zwi Migdal, seize its documents, order the closure of dozens of brothels, the conviction and deportation of numerous pimps and madams, and finally dismantle the organization with the capture of many members of the Migdal. However, out of the 434 active members who were brought to trial, only l08 were convicted of minor crimes.

The newspapers of the time displayed large front page headlines. Prostitution was banned in Argentina in 1935. As a result of Liberman’s courageous action, the papers published detailed lists of the names of the traffickers and madams that operated the Zwi Migdal. Raquel Liberman thus became a symbol for the struggle of victimized women to obtain freedom from exploitation. In literature, her example inspired the semi-fictional works of Humberto Costantini (1924–1987), Carlos Serrano, Myrtha Shalom and Nora Glickman.

Raquel Liberman died of thyroid cancer on April 7, 1935.