Jews in the Russian Empire

(Part 2 of 8)

Life in the Pale of Settlement

In the provinces of the

Pale of Settlement, Jews form approximately one-ninth of the population. As

their number increases due to the high birth rate and better medical care, the

confinement to the Pale causes growing poverty. Massive expulsions from the

villages, and the restrictions on professions and trade, increases competition

among a growing number of people.

Within the Pale, the number of artisans per 1000 persons is three times higher than elsewhere. Although the government encourages Jews to engage in agriculture, the special settlements allotted for this purpose in Southern Russia cannot absorb the tens of thousands who are driven out of the villages.

During the reign of Nicholas I, the position of the Jews deteriorates significantly. To alienate them from their religion, Jews are conscripted from 1827 onward into the army for a period of no less than 25 years.

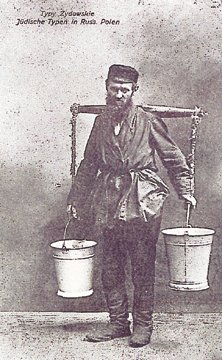

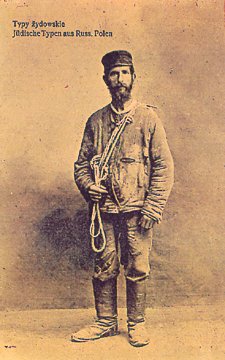

At your left a water carrier. Most cities in the Pale had no other form of water distribution than by water carrier. According to the 1898 census there were still 5,378 water carriers in the Pale. In the midlle, a familiar sight in the Pale: a porter with his rope, waiting for a work offer. At your right, cobblers and apprentices in their workshop around 1900.

The Jewish communities are made responsible for supplying a required number of recruits ("Cantonists") aged between 12 and 25. Kidnapping by so-called "khapers" is often necessary to fill the quota. The children are to be "re-educated," and compulsory instruction in Christian religion and physical pressure are used to induce them to convert. In 29 years between 30,000 and 40,000 Jewish children served as "Cantonists."

In 1843, the Jews are expelled from Kiev where they had lived for centuries. A new wave of expulsions follows when Jews are no longer allowed to live within 50 versts (1 verst = .6629 miles) of the western border.

Even government officials consider the conditions in the Pale untenable. The governor of Kiev province, where 600,000 Jews live, urges the government in 1861 to lift the residence restrictions in order to relieve the congestion in the Pale.

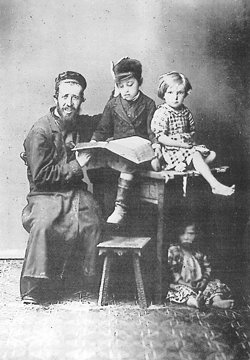

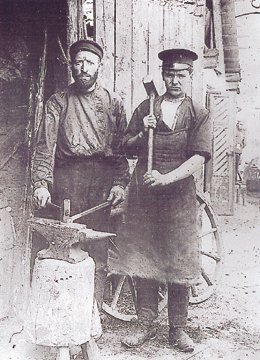

At your left, a melamed (teacher) in 19th century Podolia. Usually, the traditional Jewish kheyder was a single class school, consisting of 10 to 15 children. Only Bible and Talmud were studied. A your right, two blacksmiths in Polonnoye, Ukraine.

Outside the cities, the typical Jewish community in the Pale is the shtetl (mestechko), which usually has a few thousand inhabitants and is centered around the synagogue and marketplace. Jews earn their living as petty traders, middlemen, shopkeepers, peddlers and artisans, often working with woman and children as well.

Those who are no longer able to find any employment join the growing number of Luftmenshen - doing anything to earn a living. At the end of the century, the Jewish population has become so impoverished that approximately one-third depend to some degree on Jewish welfare organizations.

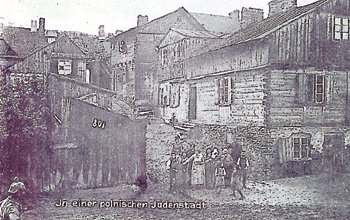

At your left, an old age home in Kiev. Pauperization in the Pale brought fourth a wide range of charitable activities, caring for the old and sick, distributing food and clothing. At your right,A German postcard from the First World War: "ln a Polish Jew Town." Even then, most of the houses were made of wood.

Although Jews are allowed to enter general schools, not many do because instructions are given in either Polish, Russian or German - not in Yiddish, which is by far the most widely spoken.

From 1844 onward, special schools for Jews are established with the purpose of bringing them "nearer to the Christians and to uproot their harmful believes which are influenced by the Talmud." A special tax on candles is imposed to pay for them.

Jewish parents regard these schools with suspicion and continue to send their children to the traditional kheyder. There, the melamed (teacher) instructs the children in the Hebrew language. As the Hebrew alphabet is also used for Yiddish, the children are able to read and write in their mother tongue as well.

The number of students attending the Jewish state schools is very small: about 6000 in 1864. Some enter the mainstream of the Russian intelligentsia, and in this respect the schools fulfill their purpose. A number of these students later join the protest movement against the oppressive Czarist regime.

At your left a Jewish wedding scene. Oil painting by Wincenty Smokowski (1797-1876).

In spite of the difficult circumstances, Jewish cultural life develops and flourishes in the Pale. From the Pale emerges a group of writers who can be considered the founding fathers of modern secular Hebrew and Yiddish literature, and many of them become world famous.