Jews in the Russian Empire

(Part 8 of 8)

Political Activity and Emigration

At the end of the 19th century, the Jewish population increases to over 5 million. Russian Jews become more assimilated, and a secular Jewish culture develops, leading to greater political participation.

The early Jewish revolutionaries among the Narodniki see themselves as Russians fighting for the right of the Russian people, and believe that the Jewish problem would be solved through assimilation after the liberation of the masses. But the generally indifferent reaction, even from the liberal Russian intelligentsia, to the wave of anti-Jewish violence in 1882 is a bitter disillusion to them.

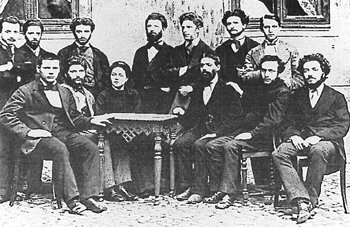

At your left, meeting of Russian-Jewish socialists in Berlin in 1875. Seated third from right is Aaron Liebermann, a pioneer of the Jewish socialist movement and founder of the first Hebrew-language socialist newspaper.

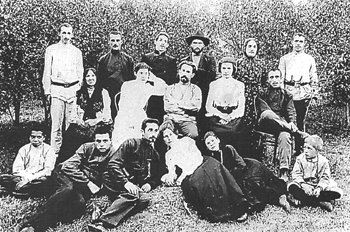

At your right, Ber Borochov (with hat), the future leader of Paolei Zion, with friends in his hometown Poltava, Ukraine, in 1903. Standing on the left is Yizchak Ben Zwi, who became the second president of Israel.

The conviction grows among Jews that the distinct economic and social discrimination targeted at them calls for the formation of a separate Jewish workers movement. In 1897, the Jewish labor movement Algemeyner Yiddisher Arbeter Bund is founded in Vilna.

The Bund advocates national and cultural autonomy for the Jews, but not in the territorial sense; it argues for a middle course between assimilation and a territorial solution. The Bund also develops trade union activities and forms self-defense organizations against pogrom violence. In 1905, it has about 33,000 members.

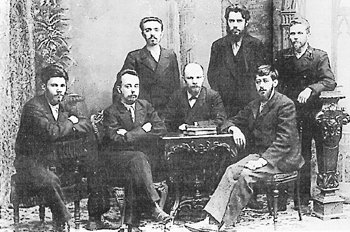

At your left, the "League for Struggle for the Liberation of the Working Class" meeting in St. Petersburg in 1905. Center: Vladimir I. Lenin; right: Julius Martov, the later leader of the Menshevik faction.

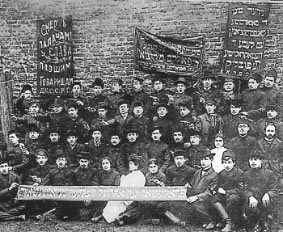

At your right, clandestine meeting of the self-defense group of the Socialist Zionist Party in Dvinsk, Latvia, in 1905. The evident approval by the authorities of the Kishinev pogrom in 1903 led many Jewish parties to form self-defense units.

The question of a national territory for Jews separates the Bundists from the Zionists. After the pogroms and the May Laws of the 1880s, many Jews no longer see any point in the struggle for emancipation within Russian society and turn after the publication of Herzl's "Der Judenstaat" in 1836 to Zionism instead. The largest Zionist party, Poalei Zion ("Workers of Zion"), founded in 1906, is Marxist in orientation and defines the establishment of a socialist-Jewish autonomous state in Palestine as its ultimate goal.

Of all the Jews active in politics, a relatively small number join the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party; most of them join the Menshevik faction after the party splits. On the eve of the Revolution, the Bolshevik party has about 23,000 members, of which 364 are Jews.

Above, Chaim Weizmann, for many years the leader of the World Zionist Congress, was born in Motol, Belorussia, in 1874. After studies in Pinsk, he emigrated to Western Europe in 1892. When the state of Israel was founded in 1948, he became its first president.

The most widespread response, though, to the continued discrimination can be found in the mass emigration of Jews to America and Western Europe. Between 1881 and 1914, more than 2 million Jews leave Russia.