PRIEST UNCOVERING BEGINNINGS OF FINAL SOLUTION

(Courtesy: MARIA DANILOVA and RANDY HERSCHAFT, Associated Press Writers)

|

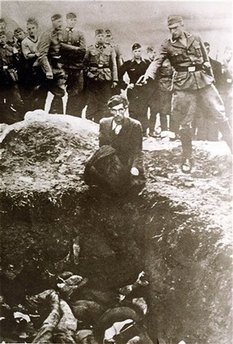

This file photo provided by Paris' Holocaust Memorial shows a German soldier shooting an Ukrainian Jew during a mass execution in Vinnitsa, Ukraine, between 1941 and 1943. For decades, the Holocaust was epitomized by barbed wire fences, gas chambers and death camps, a tragedy amply documented in history textbooks and reflected in solemn memorial sites around the world. The extermination of over 2 million Eastern European Jews by guns in the middle of quiet villages and towns across Ukraine, Russia and Belarus, has been underresearched and the victims have largely been forgotten. Many of their remains still lie unidentified and unmarked. (AP Photo/USHMM/Courtesy of the Library of Congress) |

KIEV, Ukraine – The Holocaust has a landscape engraved in the mind's eye: barbed-wire fences, gas chambers, furnaces.

Less known is the "Holocaust by Bullets," in which over 2 million Jews were gunned down in towns and villages across Ukraine, Belarus and Russia. Their part in the Nazis' Final Solution has been under-researched, their bodies left unidentified in unmarked mass graves.

"Shoah," French filmmaker Claude Lanzmann's documentary, stands as the 20th century's epic visual record of the Holocaust. Now another Frenchman, a Catholic priest named Patrick Desbois, is filling in a different part of the picture.

Desbois says he has interviewed more than 800 eyewitnesses and pinpointed hundreds of mass graves strewn around dusty fields in the former Soviet Union. The result is a book, "The Holocaust by Bullets," and an exhibition through March 15 at New York's Museum of Jewish Heritage.

Brought to Ukraine by a twist of fate, Desbois has spent seven years trying to document the truth, honor the dead, relieve witnesses of their pain and guilt and prevent future acts of genocide.

Some 1.4 million of Soviet Ukraine's 2.4 million Jews were executed, starved to death or died of disease during the war. Another 550,000-650,000 Soviet Jews were killed in Belarus and up to 140,000 in Russia, according to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. Most of the victims were women, children and the elderly.

Begun after Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, the slaughter by bullets was the opening phase of what became the Nazis' Final Solution with its factories of death operating in Auschwitz and other camps, all in Nazi-occupied Poland.

Desbois devotes his 233-page book, published by Palgrave Macmillan in August, to his work in Ukraine, where he says he has uncovered over 800 mass extermination sites, more than two-thirds of them previously unknown.

Since the book was written, he has expanded his search for mass graves into Belarus and plans to look early this year in areas of Russia that were occupied by the Germans.

Sometimes bursting into tears, old men and women from poor Ukrainian villages recount to Desbois how women, children and elders were marched or carted in from neighboring towns to be shot, burned to death or buried alive by German troops, Romanian forces, squads of local Ukrainian collaborators and local ethnic German volunteers.

Even then, it was methodical, Desbois' research shows. First, Germans would arrive in a town or village and gather intelligence on how best to transport the victims to extermination sites, where to execute them and how to dispose of their bodies.

"It was done as systematically as it was done elsewhere," said John Paul Himka, an expert on the Holocaust and Ukraine at the University of Alberta in Canada, who is not connected to Desbois' work. "You can read as they're figuring out best way to do this, the best way to shoot ... it's absolutely systematic, no accident here."

Desbois' interviews and grave-hunting tie in to millions of pages of Soviet archives, heightening their credibility, says Paul Shapiro, of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum who wrote the foreword to Desbois' book.

Father Desbois' work is also having an impact on efforts to preserve Holocaust sites. In December, the 26-nation International Task Force on the Holocaust called on European governments to ensure the protection of locations such as the mass graves Desbois is uncovering, according to Shapiro, who helped draft the resolution.

Among Desbois' key findings is the widespread use of local children to help bury the dead, wait on the German soldiers during meals and remove gold teeth and other valuables from the bodies. His work has also yielded evidence that the killings were most frequently carried out in the open, in daylight and in a variety of ways — shooting victims, throwing them alive into bonfires, walling up a group of Jews in a cellar that wasn't opened until 12 years later.

Desbois' witnesses are mostly Orthodox Christian, and he comes to them as a priest, dressed in black and wearing a clerical collar, taking in their pain and trying to ease their suffering. Many have never before talked about their experiences.

In the village of Ternivka, some 200 miles south of Kiev where 2,300 Jews were killed, a frail, elderly woman, who identified herself only as Petrivna, revealed the unbearable task the Nazis imposed on her.

The young schoolgirl saw her Jewish neighbors thrown into a large pit, many still alive and convulsing in agony. Her task was to trample on them barefoot to make space for more. One of those she had to tread on was a classmate.

"You know, we were very poor, we didn't have shoes," Petrivna told Desbois in a single breath, her body twitching in pain, Desbois writes in his book. "You see, it is not easy to walk on bodies."

Desbois, 53, a short, soft-spoken man with dark, thinning hair, says the stories give him nightmares. The most difficult is "to bear the horrors that the witnesses tell me, because often the people are simple, very kind and want to tell me everything," Desbois said in a phone interview while on a trip to western Ukraine.

"You have to be able to listen, to accept, to bear this horror," said Desbois. "I am not here to judge the people's guilt, we are here to know what happened."

Desbois' small team includes a translator, a researcher, a mapping expert, a ballistics specialist and a video and photo crew. He often joins his witnesses in their homes, leaving his shoes outside. He tends to a peasant's cow while the man tells his story.

Desbois has deep personal roots in his project, dating to 2002, when he first visited Ukraine to see the place where his grandfather was interned as a French prisoner in World War II.

When he arrived, the locals told him of a stream of blood that had run from the site where the Jews were executed and of a dismembered woman hanging from a tree after the Nazis threw a grenade in a pit full of people. When he was offered a visit to more villages, he did not hesitate.

"I am in a hurry to find all the bones, to establish the truth and justice so that the world can know what happened and that the Germans never left a tiny village in Ukraine, Belarus and Russia without killing Jews there."

The Holocaust is a divisive topic here because some Ukrainians collaborated with the Nazis. Jewish groups are grateful for Desbois' efforts and lament the lack of government support for his and other Holocaust research and education programs.

"As a Ukrainian citizen and a Ukrainian historian it pains me ... that there is no policy of national remembrance," said Anatoly Podolsky, head of the Ukrainian Center for Holocaust Studies. "We are not responsible for the past but we are responsible for remembering."

Desbois leads a French association, Yahad-In Unum (the Hebrew and Latin words for "together"), which was founded by Catholics and Jews to heal the wounds between the two faiths. He believes that as a Catholic priest talking to Orthodox believers about the killing of their Jewish neighbors his work advances that healing mission.

"The book is meant so that people know ... that a genocide is simply people killing people," Desbois said. "My book is also an act of prevention of future acts of genocide."