Courtesy of Natasha Bulashova from Pushchino, Russia, and Greg Cole of Knoxville, from Tennessee, USA.

Behind the Front

With the annexation of the Baltic states and large areas of Poland and Romania, the Jewish population of the Soviet Union is increased by more than two million. In these territories with their distinctive Jewish communities, the Soviet authorities immediately start to close down all institutions of Jewish religious, cultural and political life.

In spring 1941, tens of thousands of Jews from the annexed territories are arrested and deported to labor camps in the interior. In spite of the hardships there, they are unintentionally saved from deportation to the Nazi death camps.

The Soviet authorities are well informed about the persecution of Jews by the Nazis, but they do not pass this information on. Soviet Jews are kept ignorant about the specific anti-Jewish nature of National Socialism, and the German occupation finds them mostly unprepared. In all his war speeches, Stalin himself mentions anti-Semitism only once, in November 1941.

This policy of silence is continued during and after the war. The writer Valery Grossman sends a report in 1943 from the newly liberated Ukraine that hundreds of thousands of Jews have “vanished from the earth,” but his newspaper, the Krasnaya Zvezda of the Defense Ministry, does not print it.

scrolls outside the synagogue to be buried.

In spite of all this, the Jews of the Soviet Union take an active part in the fight against Nazi Germany. About half a million serve in the Red Army, and many volunteer for service at the front. Jewish soldiers run an extra risk: when taken prisoner, they are bound to be shot immediately. An estimated 200,000 Soviet Jews die on the battlefield.

During the war, the old anti-Semitic stereotype of Jews as cowardly soldiers is resurrected. Rumors circulate that Jews are “draft dodgers” and to “not be seen anywhere near the front.” However, when the war is over, the number of Jews awarded war decorations is proportionally higher than that of any other national group.

The Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee

In the campaign to mobilize all resources for the war, the Soviet authorities in April 1942 allow the establishment of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee. Its aim is to organize political and material support for the Soviet struggle against Nazi Germany from the Jewish communities in the West. Solomon Mikhoels, the popular actor and director of the Moscow Jewish State Theater, is appointed chairman, and many well-known Soviet Jews participate in the Committee’s activities. Since the dissolution of the Yevsektsii in 1930, the J.A.C. is the first specifically Jewish body in the Soviet Union. It has its own newspaper in Yiddish, Eynikeyt (Unity), in which contributions from the most popular Yiddish writers appear.

In 1943 Solomon Mikhoels and the writer Itzik Feffer embark on a seven-month official tour to the USA, Mexico, Canada and Great Britain. They are received everywhere with great enthusiasm: for a long time, no official contact with one of the largest Jewish communities of the world had been possible. Especially in the United States, where many Jews have not forgotten their ties with Russia, the tour is a great success, and many millions of dollars are raised for the Russian war effort.

The J.A.C. becomes the focal point of a national awakening for Soviet Jewry at a time when its very survival is in danger. Many Jews turn to the J.A.C. with requests for help, among them survivors from the Nazi camps who find their houses occupied upon their return.

The contacts with American-Jewish organizations result in the plan to publish a Black Book simultaneously in the USA and the Soviet Union, documenting the anti-Jewish crimes of the Nazis and the Jewish part in the fighting and resistance.

In 1944, the writer Ilya Ehrenburg sends a collection of letters, diaries, photos and witness accounts to the USA to be used in the book. The Black Book is published in New York in 1946. But no Russian edition appears. The typefaces are finally broken up in the printing press in 1948, a year in which the situation of Soviet Jews has once more deteriorated sharply.

The Campaign against “Cosmopolitans” and the “Doctor’s Plot”

The years following the victory over Nazi Germany are marked by a wave of Russian nationalism and the anti-Western campaigns of the emerging Cold War. Soviet policy makers, and Stalin in particular, harbor a growing suspicion about the loyalty of Soviet Jews, many of whom have relatives in the United States, now the enemy.

The mysterious murder of Solomon Mikhoels in Minsk on January 13, 1948, is an ominous sign. The same year, an increasing number of articles in the press accuse so-called “rootless cosmopolitans” of “demolishing national pride,” “harboring anti-patriotic views” and “fawning on the West.” More and more the attacks take on an anti-Jewish character, as most of the attacked bear distinctly Jewish names, often given in brackets next to their Russified names.

From November 1948 onward, the Soviet authorities start a deliberate campaign to liquidate what is left of Jewish culture. The Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee is dissolved, its members arrested. Jewish literature is removed from bookshops and libraries, and the last two Jewish schools are closed. Jewish theaters, choirs and drama groups, amateur as well as professional, are dissolved. Hundreds of Jewish authors, artists, actors and journalists are arrested. During the same period, Jews are systematically dismissed from leading positions in many sectors of society, from the administration, the army, the press, the universities and the legal system. Twenty-five of the leading Jewish writers arrested in 1948 are secretly executed in Lubianka prison in August 1952.

The anti-Jewish campaign culminates in the arrest, announced on January 13, 1953, of a group of “Saboteurs-Doctors” accused of being paid agents of Jewish-Zionists organizations” and of planning to poison Soviet leaders. Fears spread in the Jewish community that these arrests and the show trial that is bound to follow will serve as a pretext for the deportation of Jews to Siberia. But on March 5, 1953, Stalin unexpectedly dies. The “Doctor’s Plot ” is exposed as a fraud, the accused are released, and deportation plans, already discussed in the Politburo, are dropped.

Assimilatory Pressures

With the death of Stalin, the “Black Years” of Soviet Jewry have come to an end, but his successor Khrushchev allows only piecemeal reforms. In 1957, for the first time since the revolution, a Jewish theological seminary (yeshiva) opens again in Moscow. A number of amateur drama and music groups are re-established, and in 1959 Yiddish book publishing resumes after 11 years.

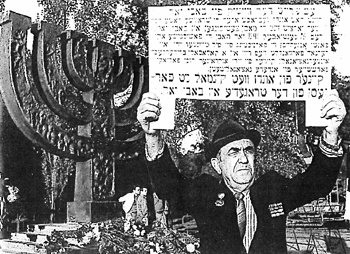

During the years of Stalin’s suppression of Yiddish culture, a few synagogues had been allowed to go on functioning. In the last years of Khrushchev’s leadership, however, a campaign of militant atheism is launched against all religions, particularly affecting Jewish institutions. Jewish cemeteries are expropriated and destroyed, and more than fifty synagogues are closed. In dozens of books, authors with Jewish-sounding names denounce the Jewish religion. Only an estimated sixty synagogues remain open in 1965.

During the same period, hundreds of trials against “economic crimes” like embezzlement and speculation are reported in the Soviet media. Mostly, the accused bear distinctly Jewish names, reviving the familiar stereotype of the Jew as a swindler and speculator.

Number and percentage of Jewish students at Moscow institutes of higher learning, 1970 – 1980. Many Jews experienced the invisible barrier of discrimination in the form of an unofficial numerus clausus.

| University year Total no. of students Jewish students Jewish students in % 1970-71 617,141 19,508 3.16 1974-75 627,285 14,985 2.39 1976-77 641,311 12,049 1.88 1978-79 632,037 11,531 1.82 1980-81 631,088 9,911 1.57 |

For Soviet Jews, all these experiences seem to point in one direction only: to assimilate completely and disappear as a distinct community. They are cut off from their language, and their culture and religion are under constant attack. Furthermore, after the wave of dismissals during the Stalin era, many fields of employment and advanced studies have become effectively closed for Jews.

The Anti-Zionist Campaign

In opposition to “Imperialist” British policy, the Soviet Union initially supports the establishment of a Jewish state in 1947. But after Israel allies itself with the West, the Soviet Union, in its search for a position of power in the Middle East, changes sides. At home, traditional suspicions against Jews as a national group also shape attitudes towards Israel and Zionism.

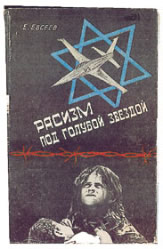

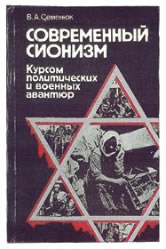

The already tense relationship deteriorates significantly after the Six Day War of June 1967. The decisive victory of Israel over its Arab neighbors, the political allies of the Soviet Union, is felt as a major debacle. In August 1967, a propaganda campaign is unleashed in the Soviet media denouncing Zionism and Israel. No distinction at all is made between Zionists and Jews.

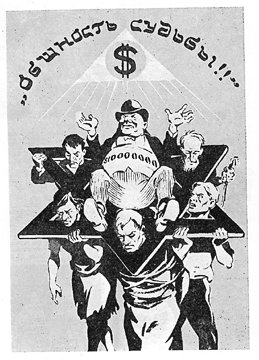

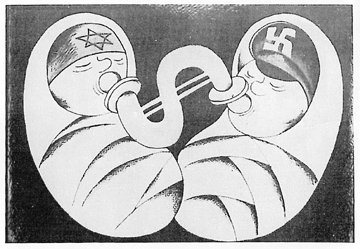

In order to discredit the policy of Israel, anti-Semitic stereotypes dating back centuries appear in political cartoons, books and television programs. Anti-Semitic allegations of a “Jewish world conspiracy” are revived in phrases like “the global international Zionist network,” active “behind the scenes” attempting to “establish world control” and supported by “smart dealers in politics and finance.” The international broadcasts from Radio Moscow for months assail “Zionism” as the greatest danger to world peace.

Particularly vicious is the equation of Zionism with Nazism, a theme introduced by the Soviet Union in a session of the United Nations as early as October 1966. This propagandistic assault could have been effective only because the general public never obtained information about the fate of the Jews under the Nazi occupation.

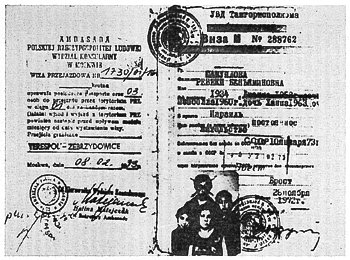

Elsewhere in the communist bloc, anti-Semitism is used for political purposes as well. In the summer of 1968, the Polish authorities blame a conspiracy of “International Zionism” for the widespread political unrest. After an overt anti-Semitic campaign, practically all the remaining Polish Jews, most of them life-long communists, are dismissed from their jobs and forced to leave the country.

The Right to Emigrate

All pressures on Soviet Jews to forgo their identity do not have the effect the authorities aim for. As Jewish cultural and religious life in the Soviet Union has become practically impossible, and even complete assimilation is no guarantee against discrimination, some Jews start to demand openly the right to emigrate to Israel.

From the end of the 1960s onward, the samizdat journal Khronika reports about an increasing number of Jews taking part in demonstrations and hunger strikes. Other activities as well testify to the growing awareness of Soviet Jews of their identity and their history.

In spite of the official silence about the extermination of Jews during the Second World War, Soviet Jews start to hold commemorations at sites of massacres during the Nazi occupation. Young Jews with hardly any knowledge of Judaism meet informally at synagogues, closely watched by the KGB, and take part in underground Hebrew lessons.

It is not long before the authorities crack down with the arrests and harassment of activists. By the end of 1970, 44 Jewish prisoners have been sent to labor camps for dissident activities. News about the trials and the activities of dissidents appear in the Western media. In many countries solidarity committees are formed. In the United States, the Jackson-Vanek Amendment of 1973 links trade relations directly to the question of Jewish emigration. As the issue of human rights is put on the international agenda, the Soviet government is faced with growing political pressure.

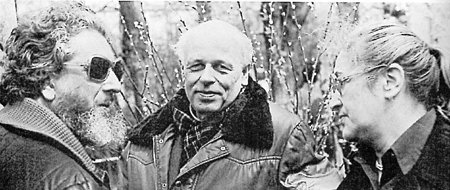

The Sakharovs with Vladimir Slepak, Jewish “refusenik” and member of the Moscow Helsinki Group, just before Slepak was sentenced to five years exile in 1978. For his human rights activities, Andrei Sakharov was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975.

Applications for exit visas usually result in dismissal, followed by months of financial hardship that carries the extra risk of arrest on charges of “parasitism.” Nevertheless, from 1971 onward, a growing number of Jews is allowed to leave: 113,800 between 1971 and 1975. These are the years of detente, marked by the signing, in August 1975, of the Helsinki Agreement. The text is published in full in both Pravda and Izvestia. In May 1976, the Moscow Helsinki Group is founded by Yuri Orlov. In the group, Jews and non-Jews cooperate in investigating and publicizing human rights violations.

The Reforms: 1985 – 1991

The reforms formulated by Mikhail Gorbachov also affect Jewish life in the Soviet Union. In February 1986, Anatoly Shcharansky is permitted to emigrate, soon followed by other refuseniks. Andrei Sakharov and Elena Bonner are released from their exile in Gorki in December.

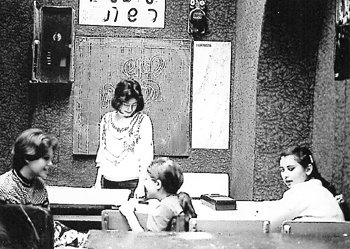

The first Jewish school to be re-established in Kiev in 1990 had to conduct its classes in an old ship rented by the community as no other accommodations were as yet available.

The revival of Jewish life begins with the formation of cultural societies for music, theater and dance. Language courses in Yiddish and Hebrew, the latter no longer a banned language, are set up. In St.Petersburg the first Jewish gymnasium is opened, and dozens of Jewish magazines and newspapers begin to be published. The growth in the number of cultural associations leads to the founding, in December 1989, of the VAAD, a national Jewish umbrella organization. Its aims are to promote Jewish life, to combat anti-Semitism and to assist in emigration to Israel.

Now that they have the right to choose where to live, a great number of Soviet Jews decide to emigrate. Between 1987 and 1991 more than half a million Jews leave the country, of which 350,000 go to Israel and 150,000 to the United States.

For decades, the number of mixed marriages has been very high, approaching 50 percent. Only 10 percent of children of mixed marriages opt for Jewish nationality. This weakening of Jewish identity, combined with large-scale emigration, has brought down the number of Jews in Russia, once the largest Jewish community with 5 million people at the turn of the century, to less than half a million.

Anti-Semitism since 1985: Old Ideas Resurface

For the first time in Russian history, there is freedom of expression: no more censorship by the state, and open discussions in the media. A great number of new newspapers and magazines reflecting divergent political opinions are appearing in the streets. But this freedom of expression also has a shadow side: anti-Semitic and racist publications appear, often published by extreme nationalistic organizations.

Cartoon from “Al-Kuds” showing the familiar image of the “Jewish” snake strangling the free press. “Al-Kuds” is published in Moscow by the Palestinian Shaban Hafez Shaban. 1994

After a few years of economic reforms, part of the population has a substantially better standard of living. Many, however, are worse off and face the future with anxiety. This situation traditionally forms an ideal breeding ground for organizations that offer simple solutions for difficult problems: blaming one specific group for everything that has gone wrong.