Courtesy of Natasha Bulashova from Pushchino, Russia, and Greg Cole of Knoxville, from Tennessee, USA.

Revolution and Emancipation

The fall of the czarist in March 1917 brings an end to decades of oppression and is greeted with joy among the Jewish community. The Provisional Government, as one of its first acts, abolishes all limitations based on religion or nationality. For the first time in their history, the Jews of Russia are free to organize and express themselves. Synagogues and schools are opened, publications appear in Hebrew and Yiddish, and political and cultural life flourishes.

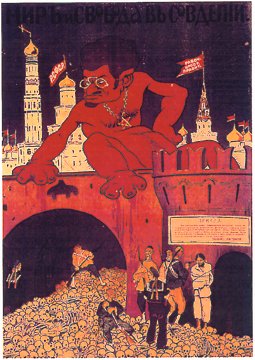

The Bolshevik seizure of power in November 1917 brings a halt to the developing Jewish communal life. The Bolshevik doctrine, as formulated by Lenin and Stalin, denies the existence of a national Jewish identity. Lenin declares national Jewish culture “the slogan of the rabbis and the bourgeois, the slogan of our enemies.” According to Stalin, the Jews are a nationality on paper only, Zionism is a reactionary bourgeois movement, and Yiddish merely a jargon. The Bolsheviks believe that once socialism is firmly established, all nationality issues will automatically be resolved.

For a period of transition, however, autonomy to national and cultural communities or to regions on a territorial base might be granted. In the case of the Jews, the result is both confusing and contradictory. The “Declaration of the Rights of the Peoples of Russia” recognizes the right to both religious and national autonomy, but subsequent decrees limit those rights profoundly. The separation of Church and State, introduced in January 1918, results in the confiscation of religious properties and the prohibition of religious instruction in schools.

The creation of special “Jewish sections” (Yevsektsii) in the Bolshevik party seems at first a recognition of a Jewish nationality. In practice, however, the Yevsektsii conduct a systematic campaign against all aspects of Judaism and Jewish life. Its first decision is the dissolution of the kehilla, the Jewish community administration, which served as the main instrument of Jewish religious and cultural life.

With the re-establishment of Poland and Lithuania in 1918, the more traditional part of Russian Jewry becomes separated from the newly founded Soviet Union where two and a half million Jews remain.

The Pogroms During the Civil War 1918 – 1921

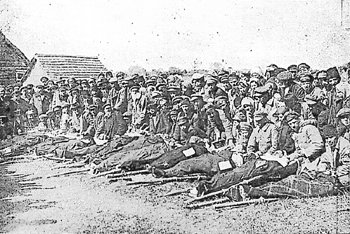

The civil war that breaks out after the Bolshevik Revolution turns the Ukraine, where 60 percent of Russian Jews live, once again into a battlefield. A number of armies, armed gangs and units, each with a different objective, enter the conflict.

In spring 1918, the Red Army has to defend itself against the Germans, the Ukrainian Army under Petlyura struggling for Ukrainian independence, and the “White” Armies under Denikin and Wrangel that try to topple the Bolshevik government. Apart from these more organized armies, armed gangs of bandits under their own leaders (atamans) join the fighting. All groups take part in anti-Jewish attacks, looting and murder. Only the Red Army Command prohibits anti-Semitic violence and even punishes some of the attackers.

No such policy is introduced in the Ukrainian Army. During 1919, when the Ukrainians have to retreat, anti-Jewish violence on an unprecedented scale claims tens of thousands of lives. None of the perpetrators is prosecuted. The majority of Jews in the Ukraine, fearful of Ukrainian independence, come to regard the Red Army more and more as the only force capable to stop the violence.

The other major participant in the Civil War, the “White” Army, also engages in looting, rape and murder, using the old slogan “Strike at the Jews and Save Russia.” When they have to retreat southward at the end of 1919, they vent their rage on Jewish communities along the way. Jewish self-defense units are occasionally able to stop them, partly with material support from the Soviet government.

By the time the Civil War is over, about 2,000 pogroms have left an estimated 100,000 Jews dead and more than half a million homeless.

Jewish Life Between the Wars

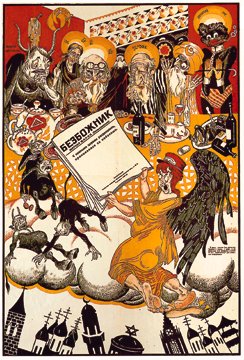

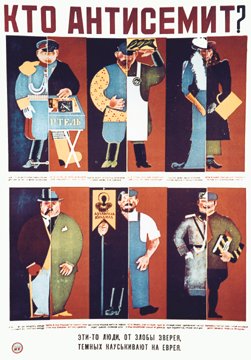

The Yevsektsii, the Jewish sections of the Communist Party, are the main instrument of the new government in applying the Marxist doctrine of forced assimilation.

The majority of Russian Jews support the various Zionist organizations; these become the first to be liquidated. Zionism is labeled “a bourgeois-clerical tendency,” and thousands of Zionists are exiled to Siberia.

The systematic attack of the Bolshevik government upon all organized religions also affects Judaism. The Yevsektsii close down synagogues and kheyders, confiscate religious books and objects, and conduct a campaign against rabbis, ritual slaughterers and other essential functionaries of Jewish religious and communal life. If they refuse to resign, they are arrested and deported.

The Yevsektsii also campaign against the Hebrew language. In their eyes, Hebrew is the reactionary language of the Jewish bourgeoisie, whatever its content, and has to be eliminated in favor of Yiddish, the language of the Jewish proletariat. Hebrew schools and printing presses are closed.

At the end of the 1920s, Hebrew becomes the only language which is officially outlawed in the Soviet Union. Jewish religious education is now impossible. The only permitted expressions of Soviet-Jewish life are secular Yiddish education, literature, press and theater. They flourish as long as they are permitted, until the mid 1930s.

The newly established Yiddish schools are very popular at first. But as only few secondary school and no university courses are in Yiddish, their numbers decline. At the end of the 1930s, they have completely disappeared.

With the almost complete elimination of organized Jewish religious and communal life, the Yevsektsii have become redundant and are dissolved in 1930. During the Stalinist purges of the late 1930s, most of its members are accused of having had “nationalist tendencies,” and are deported or killed.

The economic life of the shtetl lies in ruins after the successive disasters of the First World War, the Civil War and the years of “War Communism.” The New Economic Policy of 1921 brings some relief as farmers and artisans are once more allowed to trade their own products, but this policy is reversed with the introduction of the first Five Year Plan in 1928.

The following rapid industrialization and collectivization completely destroy the socio-economic fabric of shtetl life. Traditional Jewish occupations like shopkeepers, artisans and traders disappear, and tens of thousands of Jews have to leave their homes to work in the new industries. Because of their relatively high level of education, many Jews find employment in government services or work as doctors, engineers, managers, accountants etc. In order to promote agricultural work among Jews, and to offer a Soviet alternative to Zionism, the government establishes a Jewish Autonomous Region in the far-eastern region of Birobidzhan.

But the plan is a failure. The climate is extremely harsh, and the region is too far from the major centers of Jewish life. The Jewish population of Birobidzhan reaches its peak with 24 percent in 1937.

The massive migration of Jews out of Belorussia and the Ukraine, and the radical change in their occupational structure, result in a rapid assimilation into Soviet society. Yiddish is more and more replaced by Russian, and the number of mixed marriages rises to almost a third in the 1930s. In the lifetime of one generation, the Russian Jewish community has undergone fundamental change.