Courtesy: Centropa

Centropa is the signature project of the Central Europe Center for Research and Documentation

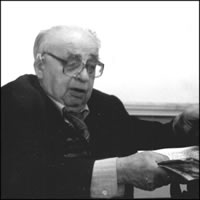

Kiev (Ukraine), Interviewer: Ella Orlikova, date of interview: May 2002

| Mark Derbaremdiker |

I was born into a family that was in direct succession to Leivi-Itshak, the Berdichev tzaddik. The tzaddik’s grave is still in Berdichev and is a place of pilgrimage for pilgrims from all over the world.

According to some data Leivi-Itshak was born in 1740. At first he was a rabbi in various Jewish communities. He lived in Berdichev as of the 1780s and was one of the famous Hasidism [1] priests. He treated common Jews with love and that has been vividly remembered in the Jewish communities up until now. Leivi-Itshak spoke Yiddish and said his prayers and addressed God in this language [God is addressed in Hebrew]. However, common Jews understood prayers in Yiddish better. His prayer Toyre tsu got in which he prayed to God to help his Jews is famous. There are also songs written by Leivi-Itshak, such as Meyerke, mayn zun [Meirerke my son – a lullaby in Yiddish].

The origin of my family name also dates back to him. In 1804, during the reign of Alexander I, the officials issued a decree to give last names to the Jews. When a clerk came to the house of Leivi-Itshak, the latter was saying his prayer shmoy yisrey [shma yisrael–] – Listen, Israel – and couldn’t stop praying. But the clerk kept asking, ‘Tell me the last name you want for yourself”. When the prayer was over the tzaddik said in Yiddish, ‘merakhemdiker got, vos vil fun mir?’, which means, ‘Merciful Lord, what does he want of me?’ And the clerk said, ‘What? Derbaremdiker?’ and put it down in his roster. Leivi-Itshak had three sons and two daughters. Successors of his older son, Meyer, stayed in Berdichev and the rest of his family moved to other towns. I have no information about them. The tzaddik died in 1809. There have been no rabbis in our family since then.

|  |  |

| These are my parents, Perl and Levi-Itshak Derbaremdiker and Perl Derbaremdiker, nee Kventsel. The photo was taken in Berdichev in 1912. | This is my mother Perl Derbaremdiker, nee Kventsel. The photo was taken in Berdichev in 1941. | This is my father Levi-Itshak Derbaremdiker. The photo was taken in Berdichev in 1941. |

Berdichev was a special town even within the restricted area of residence [see Jewish Pale of Settlement] [2]. This town is mentioned in almost all jokes about Jews, and for obvious reasons. There was a very strong Jewish community in Berdichev. In 1897 the Jewish population was 57,000, which was about 90% of the population. Our people didn’t only use the Yiddish language and culture, we lived in a Jewish cultural environment. The town’s life was based on Yiddish. This language could be heard everywhere: at home, in the streets, and all street signs were in Yiddish, too. The rest of the population – Russian, Ukrainians and Poles – were bound to adjust to this way of life. They all spoke fluent Yiddish and could sing Jewish songs. All stores and shops were closed on Friday. On Saturday Ukrainian boys and girls came to the Jewish families to light kerosene lamps and serve at the table. On the eighth day after his birth a boy was to be circumcised. When a boy reached the age of four he was taken to cheder in his father’s tallit and given into the care of a teacher – melamed – to study the alphabet, learn prayers and interpret the Torah.

On Saturday all men went to the synagogue. The most famous synagogue was Der berditsever ruvkloyz. Kloyz means synagogue. There was a very fancy old synagogue, Di alte filts. The town consisted of two parts – the old town and the new town. These two parts were very different. In the new town the buildings were high – two or three-storied. The local ‘aristocrats’ and people in administration lived there. The leaders of the community had their meetings in this part of town, too. The community was so strong that even during the Civil War [3] there were no pogroms [4] in town. Self-defense was well organized and strong: butchers with knives and blacksmiths with sledge-hammers came out and presented a real threat to the bandits. Presently there are very few Jews left in Berdichev. Most of them were exterminated during the Holocaust and the survivors moved to Israel, the USA or Germany.

I remember well my great-grandfather, my father’s father, born in 1830. His name was Yoil Derbaremdiker and he lived in the old town. He was a small, thin old man with a thin red beard. He wore a black jacket and a big black hat. He always smiled exposing his toothless mouth while patting me and treated me to apples from his big garden. They said my great-grandfather was a merchant and a successful businessman. He was a very religious man. He strictly observed all Jewish traditions and rules. At the time I remember him he couldn’t go to the synagogue any more, but he was constantly praying at home. He died at the age of 103 in 1933 when I was 13 years old.

My grandfather, my father’s father, was born in 1859. He was a merchant as well, but not as successful as his father. He died of Spanish flu in 1919 before I was born. Thousands of people died during this epidemic. My grandfather’s name was Mordko Derbaremdiker and I was named after him.

My father’s mother – I don’t remember her name – was born in 1869. She had seven children: Lazar, the oldest, was 11 and Zakhar, the youngest, was still a baby when their mother died of cholera in 1896 at the age of 27. My grandfather didn’t remarry and some relatives helped him to raise his children. All children received Jewish education, studied at cheder and got professional education. My grandfather probably couldn’t afford to give them any further education.

My grandparents’ family was religious. They strictly observed all Jewish traditions. On Friday my grandmother lit candles and the family got together at the table, which was covered with a white table cloth. On Friday afternoon my grandmother made chicken broth in ceramic pots and cholent. Cholent was a dish made from beans, potatoes and meat. The pots were left in the oven and that way the food was kept warm until Saturday, when no work was allowed. The family strictly observed the kashrut. My grandmother had different dishes for dairy and meat products and the children were learning this tradition at an early age.

|  |  |

| This is a picture of me, taken in Kiev in 1937, when I was student of the Institute of Light Industry. | This is our family photo, taken in Kiev in 1945. Sitting are my mother Perl Derbaremdiker, nee Kventsel, and my father Levi-Itshak Derbaremdiker. Standing, from left to right: my older brother Abram Derbaremdiker, I and my younger brother Yontoh Derbaremdiker. | This is a picture of my older brother Abram Derbaremdiker and his young wife Fania on their wedding day. The photo was taken in Lvov on 24th May 1947. |

My grandparents went to the synagogue every week. My grandfather wore a kippah at home and a hat outside. My grandmother wore a shawl and long black gowns in all seasons. At Chanukkah they lit one candle a day in the chanukkiyah. My father also liked Chanukkah because children received some money – Chanukkah gelt. My father had the greatest memories of Pesach. The house was to be all clean and all children took part in the cleaning process. They swept and burned all garbage, even breadcrumbs and took the Pesach dishes down from the attic. There was a bakery that was managed by the synagogue and my grandparents brought matzah from there. The family was big and they usually bought several bags of it. Then my grandmother and her daughters began to cook stuffed fish, chicken broth with dumplings from matzah and stuffed chicken necks. My granny tried to make this holiday a remarkable event to remember.

Zlata, my father’s older sister, born in 1883, lived in Berdichev and was a housewife. During the war she evacuated to Stalinabad [Dushanbe at present] with her children. She died in Berdichev in 1970. In the late 1970s her family emigrated to Israel. She had four children: two sons and two daughters. Abram, her younger son, is still alive. The rest of her children died in Israel.

|  |  |

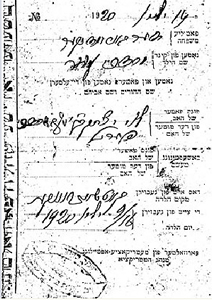

| This is my family photograph, taken in Kiev in 1951. From left to right: my wife Fira Derbaremdiker, nee Rabinovich, my daughter Sulamyth Derbaremdiker and I. | This is my birth certificate issued to me by the Jewish community of Berdichev in 1920. | This is my wife Fira Rabinovich, at the age of four. The photo was taken in Kiev in 1927. |

Lazar, my father’s older brother, was born in 1885. He was a shornik [leather cutter]. In the 1920s he moved to Leningrad with his family. All his children received higher education: Asia, born in 1912, an engineer, has already died. Abram, born in 1915, an economist, lives in Rostov-on-Don. Frieda, born in 1920, is an economist, and Haya, born in 1928, is a dentist. The two of them live in New York now. Lazar died in 1943 during the blockade of Leningrad [5].

My father’s sister Hasia, born in 1890, died of some illness in Berdichev in 1911. His other sister Milka, born in 1892, died during the famine [6] in 1932 in an effort to save her four children from starving to death, and giving them every last piece of bread. Her two girls, Klara and Honia, were sent to an orphanage – her husband, who was a tinsmith couldn’t provide for them, and her boy, Lyova, also disappeared at that time. Elka, the youngest girl, and her father perished in 1941 when the Germans occupied Berdichev.

Feiga, the youngest of my father’s sisters, born in 1893, moved to Birobidzhan [7] with her family in 1932. Life was hard and miserable there. In 1942, when Zlata was in evacuation in Stalinabad, Feiga’s family moved in with her. Her older son Grisha perished at the front and her second son Matvey, born in 1928, and her two daughters, Asia and Shyfra, left for Israel in 1989. Shyfra died there. Feiga died in Dushanbe in 1969. I correspond with all my relatives in Israel.

My father Levi-Itshak was named after his famous great-grandfather. He was born in 1887. Before the Russian Revolution [of 1917] [8] he worked as a clerk in a store. During World War I he served in the tsarist army as a private in Kiev. He learned to speak and write in Russian. After his retirement from the army he became a craftsman. After the Revolution my father changed many professions to provide for his family. I remember he was a soap-boiler at some stage. He worked in our kitchen where he had a big boiler to make soap. He bought beef fat and all necessary ingredients, mixed them together and boiled them for a long time stirring the mixture with sticks. Then he poured it into special forms. The whole family was involved in this process. Of course, it smelled awful but we got used to it.

In 1928 the NEP [9] came to an end and my father went to work at a shop. At one time he even was the manager of a shop, as he was more intelligent than the others. The Soviet power struggled against religion [10] and declared Saturday a working day. My father didn’t like to argue. He went to work on Saturday but didn’t do anything on this day. For the rest of his life my father was involved in soap and soda powder production. He was a kind, wise and considerate man. In the evening he used to read books and newspapers in Yiddish to the family. I still have newspaper cuttings from 1897-1898. They certainly have historical value. When the Jewish center opens in Kiev I will take them there. My mother was always my father’s most passionate listener.

My mother came from the family of Kventsel – a very respected family in Berdichev. Her father Oizer Kventsel was born in 1860. He owned a kerosene store. Unfortunately, I never met my grandfather. He and his wife Entel died of Spanish flu in 1919. But I remember well my grandfather’s brother Meyer. He was my first teacher of Yiddish. Meyer taught Yiddish to many boys in Berdichev. He died in the late 1930s. His daughter Eti lived in Moscow and also died a long time ago.

My mother’s name was Perl. She was born in 1890 and received a good education at home like many other girls in Berdichev. She was taught to read and write in Yiddish, do the housekeeping and meet Saturday in accordance with all the rules: clean up the apartment, bake challah on Friday, light Saturday candles, be a faithful wife and cook Jewish food.

I don’t know whether my mother had any brothers or sisters. My father and mother were introduced to one another in 1911. On some Jewish holiday their mothers met in the synagogue, discussed the issue with other relatives and arranged that they should meet each other. The young people liked each other and got married in 1912. They had a Jewish wedding with a chuppah, a bunch of relatives as guests, and there were merry songs and dances, freilakh.

|  |  |

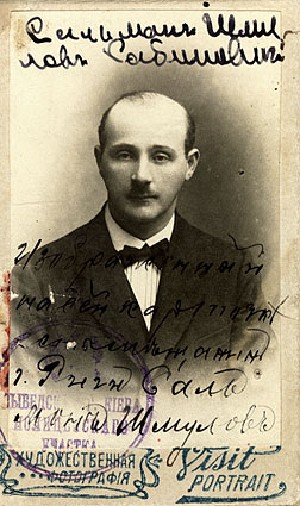

| This is my wife Fira Rabinovich’s mother Rosalia Rabinovich, nee Ratmanskaya. The photo was taken in Kiev in 1912. | This is the family of my wife Fira Rabinovich. From left to right: my wife Fira, her older sister Sulamyth Rabinovich and their mother Rosalia Rabinovich. The photo was taken in Kiev in 1928. | This is my wife Fira Rabinovich’s father Saliman Rabinovich. This is the photograph on his identity card. The picture was taken in Kiev in 1916. |

My older brother Abram was born in 1913. He studied in cheder and then, after the Revolution, in a Ukrainian school for a few years. He studied for eight years and entered a Jewish technical school. He studied very well. Before the war he finished the physics and mathematics department of Berdichev Pedagogical Institute. Then he was recruited to the army and was on the front during the war. After the war Abram decided to change his profession and entered the Academy of Agriculture. He became a specialist in the field of electrification of the agricultural sector. He worked in Lvov for many years. In 1947 he married his co-student Fania, who is also a Jew, of course. In a year their son Eduard was born. They are a wonderful family. They emigrated to the USA and lived in New York now. Fania died in 1987. My brother is a pensioner and Eduard is a programmer.

My younger brother Yontoh, or Yan, followed them to New York in the 1990s. Yontoh was born in 1923. He finished school before the war and was recruited to the army. He served as a private at the front during the war. Thank God he survived and came back. He studied at the Kiev Institute of Light Industry and became a good footwear specialist. He lives in New York with his family now. His son Peter, born in 1956, became a businessman and his grandson Igor works in a bank. Both my brothers are active members of the Jewish community in New York; they live a Jewish life. They promote the Jewish culture and Yiddish. We write to each other and they often call me on the phone. We have been very close throughout our life.

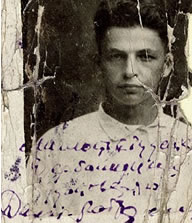

I was born in Berdichev on 9th July 1920. My Jewish name is Mordke-Oizer Leivi-Isaakovich. The leadership of the Jewish community issued my birth certificate in two languages: Yiddish and Hebrew. My date of birth is also given according to both the Jewish and the modern calendar. I was born a few days after the Red Army entered Berdichev and declared the Soviet power. The Civil War was over for Berdichev. My father told me that the Bolsheviks began shooting the ten richest Jews in town, not because they were Jews, but because they were rich.

The house where I was born was located in Kachanovka between the old and the new town on the hilly bank of the Gnilopiat River. However, I didn’t live there long. It was damaged during the Civil War – when the town was occupied by the reds [11] and by the greens [12] many times in a row – and our family had to move to another house on the corner of Zolotoy Lane and Kachanovskaya Street. We lived in the apartment that previously belonged to Moiher Sforim Mendele [13], the famous Jewish writer. Later Zolotoy Lane was renamed Moiher Sforim Mendele Street.

The house was located at the bottom of the hill; therefore it had two floors, one from the street and one floor from the side of the yard. We lived on the second floor. We had two big rooms and a big kitchen, which also served as my father’s shop. We had antique furniture in the rooms like carved wardrobes, etc. My parents had a big nickel-plated bed, which was their wedding gift. Mama baked bread every Monday and challot for Saturday on Thursday. This was a difficult time and Mama couldn’t always afford to cook a festive Saturday dinner. Sometimes we just had potatoes and herring, but the kashrut was strictly followed anyway. Dishes for dairy products were on a separate shelf. Before Pesach Mama took special dishes out of a box and cleaned the apartment thoroughly. Mama only spoke Yiddish. When peasant women brought food products from the nearest villages Mama could hardly communicate with them in Ukrainian.

|

| This is a picture of my wife Fira Rabinovich and my daughter Sulamyth Derbaremdiker. The photo was taken in Kiev in 1960. |

At the age of four I went to cheder like many other boys in Berdichev. I studied there until I reached the age of seven. There were about 20 of us in cheder. We were sitting at a long table and took turns to come to the teacher [rebbe] to read prayers. The rebbe was allowed to spank naughty boys or those that didn’t read well. I can’t remember being punished, so I suppose I behaved and studied well. The rebbe’s name was Itsyk Galitskiy and he was an old man. His daughter was a nurse. During the intervals we played games in the hallway and in summer we played outside. My younger brother Yontoh also went to cheder.

In 1922 the authorities began an active campaign against religion – any religion was called obscurantism. It reached Berdichev several years after I had finished cheder. Our cheder was closed before my brother could finish it. At the age of seven I went to the Jewish secondary school. In 1922 the authorities decided to open schools for national minorities. Jews also were considered to belong to the national minority. There were five or six Jewish schools in Berdichev. My school was named Grinike Boymelakh – a green sapling. The teaching there was in Yiddish, but there were no special subjects related to Jewish history or traditions.

I remember my first teacher Fania Abramovna Rabinovich. She was a Jew. She taught us arithmetics and poems about Lenin in Yiddish. We all became pioneers, but I wasn’t an activist. My father believed that one shouldn’t live in conflict with the authorities, but at home we could have our own way of life, observing our rules and traditions. At school there were small groups of children that visited other children’s homes to see how they celebrated Pesach or ate matzah and then condemned them at the meetings. But these ‘inspectors’ and those that were ‘inspected’ enjoyed eating all Jewish food! We had classes on Saturday, but we tried to leave pens and textbooks at home and therefore we didn’t really do anything in class. We were like marans [Editor’s note: Jews in medieval Spain that were forced into Christianity, but practiced Judaism in secret]. We were like this: we were pioneers at school, and at home we followed the rules of Judaism.

In 1933 I reached the age of 13 which means for a Jewish boy to come of age – the bar mitzvah. My parents hired a rebbe for me to review the Torah and the Talmud. I answered all questions, learned by heart articles from the Torah, passed my test in front of the rebbe and my relatives and became an adult. This was all kept secret. If somebody had found out my parents would have had a problem. They had a difficult life anyways. My father was looking for a job to provide for us. He traveled to small towns and took me along once in the summer of 1927. We went to Pogrebysche. My father was boiling soap there, too. We went there by train and then on a cart on the bridge across the Ros River. I woke up when we were halfway across the river and got very scared. This was my first trip ever. Later my father got a job at a shop. Mama also found a job at a shop, but she often took home work, as she had a sewing machine.

I remember well the early 1930s, the period of collectivization [14] and famine. We saw dead corpses in the streets. Many Jews in Berdichev were starving to death. We had charity lunches at school and it was a big joy to see a piece of cabbage in the soup that we got. The teachers were as hungry as their students. Many people moved to bigger towns that had better supplies. They sent parcels with bread or crusts from there. When the parcels were delivered the bread inside was already covered with mold but we ate it with pleasure. My father and older brother were working and we managed somehow. They received bread cards.

My parents still went to the synagogue. My father went there each Saturday and my mother went on holidays. At Yom Kippur everybody fasted. We, children, were allowed to have some food after 3pm. There was one synagogue in Kachanovka. There was one servant there, a humpback. I heard later that when Germans came they ruthlessly killed him at the threshold of the synagogue. All synagogues were closed [there were over 100 synagogues in Berdichev before 1920].

The former Choir Synagogue housed a Jewish club of polygraphic employees. It was called ‘Epikoyres’, which means ‘heretic’ – there could be no other name for this club. There was a library in this club. I remember the ‘Cleaning up the Party’ meeting in this library. [Editor’s note: In 1930 the Communist Party decided to get rid of any doubtful members and there were many meetings held to condemn unfaithful members.] I remember one Jew had to report in front of his comrades. They asked him, ‘Who is Stalin?’, and he said, ‘He is the chief of the Soviet power’. This was tragic and comic at the same time.

We subscribed to Jewish newspapers and magazines as long as it was possible. We also attended the literature club at the town library, led by Moshe Gelmont, a poet. There were teachers and editorial staff there and just amateurs of all ages. Vevik, Sholem Aleichem’s [15] brother, also attended this club. He was a glove maker. He wrote and published a book called My brother Sholem Aleichem with the assistance of Gelmont. The Jewish regional newspaper published works by members of the club. A poem of mine in Yiddish was also published there. It was later translated into Ukrainian and published in the local newspaper.

Back then we all wrote, but this was in adolescence only, afterwards I didn’t concern myself with this task. My friend Shmuel Aizenwarg was the most talented among us. He perished on a submarine in 1943. In 1985 his poems were published in ‘Leaderkrantz’, dedicated to the deceased Jewish poets. This book was published by the Moscow publishing house Soviet Writer. There were many books in Yiddish in our library, including translations of world classics: Shakespeare, Cervantes, Goethe, etc. I read Crime and Punishment by Dostoevsky [16] and Les Miserables by Victor Hugo in Yiddish. I was very fond of literature but my parents understood that literature at that severe time was similar to politics and they tried to stay away from any politics.

My father recommended me to study to become an engineer. My Russian and Ukrainian was poor and I started learning these languages at 15. We had Pushkin [17] in Russian and Shevchenko [18] in Ukrainian. I learned their poems by heart and wrote them down. This helped a lot. I did well in mathematics, physics and chemistry. I studied a lot and finished the 9th and 10th grades in one year. I had to rush with my studies to start helping my father. In 1936 I arrived in Kiev and entered the chemistry department of the Institute of Leather Industry. I liked chemistry. My father was a soap-boiler, almost a chemist you could say. He could make other chemical materials like shoe polish, soda powder, etc. Almost all my co-students were Jews. There were probably three students that weren’t Jewish. The director and dean were also Jews, and so were many lecturers. It was the same in many other educational institutions. It was because previously Jews hadn’t been allowed to study [see five percent quota] [19].

In the 1920s we were the first to go to schools and then continue our studies. I was an excellent student; we all were trying to do our best. I became a Komsomol [20] member when I was a 2nd or 3rd-year student. However, during the war I lost my Komsomol membership card and never restored it. I also tried to avoid becoming a party member, not because of my political views but because I wasn’t interested. I lived in a hostel on 32, Gorvits Street [Bolshaya Zhytomirskaya at present]. The building of our institute was under construction in Pechersk. We used to go to the construction site. We stated our studies there when we were in our second year. Chemical laboratories were on the first and second floors in the new building and our hostel was on the third and fourth. I lived there until 1939. Then we had to move to another hostel on Vladimirskaya hill, as our floors were to house some official institutions.

There were six of us in the room. They were all different people. One was Geifman, a Jew; his uncle worked for a Jewish newspaper. Two or three other tenants were Ukrainians. We were on friendly terms. We received scholarships but they didn’t last long and we either starved or borrowed a glass of tea and some vegetable salad to survive until the next pay-day. My parents couldn’t support me. When I visited them my mother gave me some food to take with me. She melted some butter and honey and mixed them together. I couldn’t keep Jewish traditions. My mother cooked kosher food, but what we ate in our canteen wasn’t kosher food. We had no choice. We never ate pork in my childhood, and, although I didn’t follow the kashrut, I didn’t eat pork. I remember the authorities were planning to close two synagogues in Podol [21], Kiev, before the war. They were collecting signatures among the students. They didn’t get my signature. In Kiev I still read books in Yiddish and bought newspapers. There was a Jewish theater in Kiev before the war. I saw all the performances. I remember when the Moscow theater Goset [Jewish state theater] under the leadership of Mikhoels [22] was on tour. I am still under the impression of his acting – never again have I seen such a great King Lear!

I finished my studies at the institute in 1941. On 20th June I defended my thesis. I was about to receive my job assignment to the leather factory in Berdichev, but on 22nd June the Great Patriotic War [23] began. We heard explosions at night and we didn’t understand what was happening. We went to Vladimirskaya hill and then down to Kreschatik [main street in Kiev] and we still didn’t know anything until we heard the 12 o’clock announcement on the radio. I was aware that the situation had been alarming for some time. But we thought we were friends with Germany following the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact [24] signed in 1939.

The situation in the city changed beyond recognition. Within a few days we were summoned to build defensive structures. Quite a few were recruited to the army right from the construction site. I wasn’t taken to the army due to my poor sight. We worked at digging anti-tank ditches. We met young people escaping from Poland that told us about the Germans’ attitude towards Jews. Nobody knew how the situation was going to develop. I don’t think Germans realized what kind of public opinion their actions would result in. Therefore, Babi Yar [25] and the tragedy in Berdichev were the beginning of the tragedy they were heading to. Perhaps, the world might not have seen Auschwitz or the gas chambers if there had been a decisive reaction of the world community to the beginning of the war.

At the Institute I received a [mandatory] job assignment [26] to Kursk. This gave me the right to leave Kiev. My parents had left Berdichev on 6th July – one day before the German army arrived there. The families that were leaving put their luggage on a horse-drawn cart and walked to Mironovka station. They were trying to get on the train there, but it was so overcrowded that they only managed to push Mama in the train. My father and my younger brother stayed in Mironovka. I was still involved in the digging of those anti-tank ditches. Once we were woken up at night and somebody said, ‘Run away from here, the Germans are approaching. Go to Kiev’. We went to Kiev on foot. I arrived at the hostel in the morning.

My father’s younger brother and his family lived nearby, on Kostyolnaya Street. I decided to visit them and met with Mama. Her Russian was poor and she could hardly find their building. We lived with them for several weeks. Later my uncle and aunt evacuated to Dnepropetrovsk with the Opera Theater. I stayed with Mama. My father and brother joined us in a few days. We all went to the Botanical Garden [railroad ticket offices were located there] and saw people from all parts of Ukraine sitting around on benches and everywhere. We waited for a while when a truck arrived and somebody told us to board it if we wanted to get away. We got on the truck – my mother was still weak, as she had been ill for some time – and got a ride to the railway station where we got on a train, on an open platform, and the train left.

We were bombed many times and got off the train when it stopped. We reached Kupiansk and were trying to get to Kursk. But people weren’t allowed to go to Kursk because there were already too many evacuated people there, so we got on a train again to move on. We got off at some place in Stalingrad region. It was a Kazak village. We were helping the locals with the harvest. They treated us all right. Nationality didn’t matter. We were all in common trouble and facing a common danger. We were accommodated in a house. We slept on the floor. It was summer and hot, so sometimes we also slept outside. We didn’t stay long in Stalingrad region.

My brother went to Stalingrad. He wanted to finish his second year at the institute. He was mobilized to the front from there. We knew we had to move farther to the East. Orsk nickel factory in Chkalov [today Orenburg] region employed people and we went there. Here is what happened at the railway station in Chkalov: An old man asked me, ‘Who is a Jew here? Tell me, dear, who is a Jew here?’ I replied, ‘I am’. He said, ‘It can’t be. They say Jews have horns’. People in these areas had never seen Jews before the war, and there were all kinds of incredible rumors that made them be anti-Semitic.

We went to Kuibyshev [Samara at present] on a boat. We saw the Germans bombing the boats. One boat ahead of us sank, but we reached Kuibyshev and from there we traveled on to Orsk. I found out that there was a leather factory under construction there and I went to work there. We produced thick leather for special boots for the metallurgical industry and later we began with the production of sheepskin coats for army commanders.

We got a small room for the shop and plastered it. My father made a stove to heat this room. Orsk has continental climate – very cold in winter and hot in summer. The factory where I worked was about two kilometers from the city. I had to walk there when either the heat was oppressive or when it was exceedingly cold. There weren’t many Jews in Orsk. Some of them were residents and some had been evacuated from other regions.

Within some time my father went to work at the soap-making factory. We were paid in cards for which we could receive bread. After a while our factory fused with the meat factory. They boiled bones in big bowls and we could have this broth. We planted potatoes around the factory to have some additional food to survive on.

When it was time for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur my parents got to know that there were Jews in Orsk and that one of them had a prayer house at his home. My mother and father went there, but I didn’t. Somehow I didn’t quite feel like going there. There were many Jewish refugees from Poland. I remember an artist from Lodz and a clock specialist with his daughters.

I heard about what was happening in Kiev and Berdichev in 1943. I read the article by Erenburg [27]. By the way, I was a regular attendant of the town library where I read Eimikait – in Yiddish – the newspaper published in Moscow by the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee [28]. All members of this committee were shot by the Soviet authorities in 1940 for their true description of the genocide of fascists on the Jews and the indifference of the authorities. Although I worked 12-14 hours, I always found time to take an interest in the Jewish life. At 3am on 9th May 1945 [Victory Day] [29] we were at work at the factory when we heard that Germany signed the document about its unconditional surrender. Everybody was outside shouting, ‘Victory!’ My mother was crying. My older brother wrote to us saying that he had been in Berdichev. Some people lived in our house. I was told later that there were only few Jews left in Berdichev.

I returned to Kiev in 1945 after I received a request to work and an invitation to continue my post-graduate studies. Professor Kotov, our former head of department, became the director of the Research Institute of the Leather Industry. He liked me a lot and sent me a request to accept a job offer at the institute that gave me an opportunity to return to Kiev.

My parents returned with me. I got a room in a hostel. My parents lived at my uncle’s for a few days and then left for Berdichev. They didn’t receive a warm welcome there and they didn’t get their apartment back. The attitude towards Jews changed dramatically in Berdichev. They decided to leave it at that and moved to Kiev. We received some kind of a dwelling in the basement of a building. It was dark and damp there and my father and I did some renovations to make it a livable place. My parents lived there for many years. My mother died in 1952. She was ill for the last three months of her life – there was something wrong with her stomach or something. My mother and father went to the synagogue in Podol until their last days and tried to observe Jewish traditions, however hard it was in these conditions. In 1961 my father received an apartment in a new neighborhood in Kiev, Otradny, but he didn’t stay there long. He wasn’t feeling well and we took him to our place. He died in 1972.

My father always said to me, ‘You live in this new difficult world. You were raised as a Jew and you went to cheder. Whatever happens in your life don’t change your nationality’. And I never did. I followed what he told me. [Editor’s note: At that time quite a few Jews were assimilating into communities by having a different nationality written in their passport or marrying someone of a different nationality, etc.] We heard that wives were giving away their Jewish husbands to the fascists. Once an officer – he was a Jew – returned from the front to find out that all his family members had been killed by the Germans. When he heard the word ‘zhyd’ [kike] in the street he shot somebody and he was sued and shot.

During my post-graduate course at Kiev Light Industry University, in 1947, I met my future wife. She was a student at the institute. Her name was Fira, Esphir Salimanovna Rabinovich. She was born into a respected Jewish family in 1923.

Her father Saliman Rabinovich came from a big assimilated Jewish family. He came to Kiev from Riga. He was a big china specialist and worked in famous china factories. He met his wife, Rosalia Ratmanskaya in 1911. He died of spotted fever in 1933. My wife didn’t know Yiddish. Her father took her to the synagogue several times when she was a child. Fira worked at a hospital at the front. She was awarded the Order of the Great Patriotic War. Her grandmother and grandfather were killed in Babi Yar. Her grandmother’s name was Lubov and her grandfather’s Wolf Ratmanskiye.

After Fira and her mother returned to Kiev in 1944 they lived in the hospital for some time and then they received a room on Saksaganskogo Street – and that replaced their nice apartment in Pushkin Street that they had before the war.

We got married in 1948. We didn’t have a wedding party, only a civil registration ceremony. Fira was a very nice, talented, intelligent and reserved Jewish woman, exactly the woman that my parents would have wanted me to marry.

Our daughter Sulamyth was born in 1950. She got her name from my wife’s sister Sulamyth, who died of spotted fever when she was young. Our daughter finished school and worked as a masseur specialist for some time. But she hasn’t worked for a long time, she is very ill and I don’t want to talk about her disease. [The interviewee’s daughter is mentally ill.]

It seemed at first that Jewish life was improving in Kiev. There was a Jewish theater in the beginning but it didn’t stay here because the building in which it was housed was destroyed. The theater moved to Chernovtsy. The Jewish culture department at the Academy of Sciences was restored. Spivak, an outstanding scientist, was its director. I went to all open meetings arranged by this department. Once I went there on business. We had a relative in Berdichev, Frenkel. He was a cantor in synagogues and sang Jewish songs. This department of culture had a music section, headed by Beregovskiy. I took Frenkel to Beregovskiy. I don’t know what their discussion resulted in as I had to go somewhere else. In 1948 I received the last issues of Der Shtern magazine. Its editor was Grigoriy Polianker, a Jewish writer. I even wanted to go to the post office to find out why they had stopped delivering it to me. But somebody told me to not even mention that I had ever received this magazine. I heard at that time that the authorities were arresting all Jewish writers. They arrested Polianker, too. The Department of Culture employees were also arrested. Spivak died in jail.

In 1953 Stalin died. I was naïve enough to think that Stalin hadn’t known about what was going on in the country. I grieved a lot after him.

After I finished my post-graduate studies I waited for my job assignment. I found a job at the Institute of Communal Hygiene and they sent a request to have me there. But my institute refused to let me go and offered me a job. In less than two months I was fired due to staff reduction. They fired almost all Jews at once. In that other institute they also told me that the vacancy had been filled. I wrote to Moscow but in vain. I realized this was part of the anti-Semitism, which was at its height in the late 1940s.

My wife was finishing her course at the Institute. She was an excellent student but of course there were no good vacancies in store for her due to her typical Jewish surname – Rabinovich. She was sent to the rubber factory. I had no job. I wrote to different institutes, but I had no success. Then I found a job at the leather factory. They had a research institute there and I asked them to send me to work there, but they told me it was out of the question. I worked at the plant and became a rationalization engineer, chemical engineer and then I was promoted to head of a shop. Later I became head of the central laboratory and worked there until 1965. From then on and until 1996 I was a senior researcher and director of the laboratory.

In 1962 I received a small three-bedroom apartment on the outskirts of Kiev. It took my wife about two hours to get to work. Then she got a job at the institute of extra-solid materials, located in our neighborhood. She was successful at her new workplace and created many new materials and tools. She defended her thesis. We lived a good life. We had interesting jobs and many friends. We never celebrated Soviet holidays, but we got together at weekends and had parties. We celebrated birthdays and always tried to celebrate Jewish holidays, although my wife didn’t know anything about traditions. But she learned to cook Jewish food and we fasted at Yom Kippur. However, we didn’t go to the synagogue.

I’ve always been interested in Jewish literature. Between 1948 and 1961 nothing was published in Yiddish and I read the books that I had bought before 1948. Books about the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising [30] or about the Minsk ghetto were published before 1948. Yiddish authors were also published before 1948. In 1961 they began to issue the magazine Sovyetishe heymland in Yiddish. Of course, this magazine published the works that were praising the Communist Party. They allowed no stories about anti-Semitism.

I’ve never concealed my nationality or my interest in the Jewish culture. I’ve always treated people nicely and they were nice to me, too. Neither I nor members of my family faced any anti-Semitism in our day-to-day life. I always behaved in a manner that people respected my nationality. If I ever heard any statements related to this subject I talked back in such a way that people tried to avoid arguing with me.

Life has changed a lot in the recent 12-13 years. There is a young enthusiastic rabbi in Kiev – Rebbe Yankel. He brought the people interested in the Jewish culture together. A Jewish school was opened and Igor, the son of my brother Yankel, went there. We all began to go to the synagogue. I went on Saturdays and heard there about a group of people called ‘Yidish gayst oyf Yidish’ – ‘Jewish spirit in Yiddish’. They got together for discussions. Rebbe Yankel held speeches several times. After I retired from work I started to go to the synagogue twice a day – in the morning and in the evening. I recalled everything that my parents had taught me. I am following the kashrut now. We also celebrate Jewish holidays. When Solomon University [Jewish University in Kiev, established in 1995] was opened I created a course in Yiddish for them. It doesn’t exist any more now. I took part in all conferences of experts in Yiddish. Regretfully, there are fewer and fewer people that understand the language of Eastern European Jews, the language of Sholem Aleichem. The culture that gave the world great artists, musicians and scientists is about to disappear.

My brothers live in America. I was supposed to move there, too, but it happened so that we couldn’t leave due to my wife’s illness. She died in 1995. She had trombophlebitis and lymphostasis, but she was infected with an injection. It doesn’t make sense to try and prove anything – she is gone. It’s difficult to talk about it.

It’s not possible to leave this country with my daughter because she is ill. There is a totally different culture in Israel and any efforts of Eastern European Jews to restore the Yiddish culture fail. I work and write articles in Yiddish and about the history of Jews from Berdichev.

I’m very interested in the life in Israel. Regretfully, I haven’t had a chance to visit this country. The situation there gives me much concern. Why don’t they leave the Jewish state alone? This terrorism is just awful. I think it’s even worse than a war. At least one realizes during a war that one is in a war. I wish that everybody could live in peace, have no fear and be happy.

Glossary:

[1] Hasidism (Hasidic): Jewish mystic movement founded in the 18th century that reacted against Talmudic learning and maintained that God’s presence was in all of one’s surroundings and that one should serve God in one’s every deed and word. The movement provided spiritual hope and uplifted the common people. There were large branches of Hasidic movements and schools throughout Eastern Europe before World War II, each following the teachings of famous scholars and thinkers. Most had their own customs, rituals and life styles. Today there are substantial Hasidic communities in New York, London, Israel and Antwerp.

[2] Jewish Pale of Settlement: Certain provinces in the Russian Empire were designated for permanent Jewish residence and the Jewish population was only allowed to live in these areas. The Pale was first established by a decree by Catherine II in 1791. The regulation was in force until the Russian Revolution of 1917, although the limits of the Pale were modified several times. The Pale stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, and 94% of the total Jewish population of Russia, almost 5 million people, lived there. The overwhelming majority of the Jews lived in the towns and shtetls of the Pale. Certain privileged groups of Jews, such as certain merchants, university graduates and craftsmen working in certain branches, were granted to live outside the borders of the Pale of Settlement permanently.

[3] Civil War (1918-1920): The Civil War between the Reds (the Bolsheviks) and the Whites (the anti-Bolsheviks), which broke out in early 1918, ravaged Russia until 1920. The Whites represented all shades of anti-communist groups – Russian army units from World War I, led by anti-Bolshevik officers, by anti-Bolshevik volunteers and some Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries. Several of their leaders favored setting up a military dictatorship, but few were outspoken tsarists. Atrocities were committed throughout the Civil War by both sides. The Civil War ended with Bolshevik military victory, thanks to the lack of cooperation among the various White commanders and to the reorganization of the Red forces after Trotsky became commissar for war. It was won, however, only at the price of immense sacrifice; by 1920 Russia was ruined and devastated. In 1920 industrial production was reduced to 14% and agriculture to 50% as compared to 1913.

[4] Pogroms in Ukraine: In the 1920s there were many anti-Semitic gangs in Ukraine. They killed Jews and burnt their houses, they robbed their houses, raped women and killed children.

[5] Blockade of Leningrad: On September 8, 1941 the Germans fully encircled Leningrad and its siege began. It lasted until January 27, 1944. The blockade meant incredible hardships and privations for the population of the town. Hundreds of thousands died from hunger, cold and diseases during the almost 900 days of the blockade.

[6] Famine in Ukraine: In 1920 a deliberate famine was introduced in the Ukraine causing the death of millions of people. It was arranged in order to suppress those protesting peasants who did not want to join the collective farms. There was another dreadful deliberate famine in 1930-1934 in the Ukraine. The authorities took away the last food products from the peasants. People were dying in the streets, whole villages became deserted. The authorities arranged this specifically to suppress the rebellious peasants who did not want to accept Soviet power and join collective farms.

[7] Birobidzhan: Formed in 1928 to give Soviet Jews a home territory and to increase settlement along the vulnerable borders of the Soviet Far East, the area was raised to the status of an autonomous region in 1934. Influenced by an effective propaganda campaign, and starvation in the east, 41,000 Soviet Jews relocated to the area between the late 1920s and early 1930s. But, by 1938 28,000 of them had fled the regions harsh conditions, There were Jewish schools and synagogues up until the 1940s, when there was a resurgence of religious repression after World War II. The Soviet government wanted the forced deportation of all Jews to Birobidzhan to be completed by the middle of the 1950s. But in 1953 Stalin died and the deportation was cancelled. Despite some remaining Yiddish influences – including a Yiddish newspaper – Jewish cultural activity in the region has declined enormously since Stalin’s anti-cosmopolitanism campaigns and since the liberalization of Jewish emigration in the 1970s. Jews now make up less than 2% of the region’s population.

[8] Russian Revolution of 1917: Revolution in which the tsarist regime was overthrown in the Russian Empire and, under Lenin, was replaced by the Bolshevik rule. The two phases of the Revolution were: February Revolution, which came about due to food and fuel shortages during World War I, and during which the tsar abdicated and a provisional government took over. The second phase took place in the form of a coup led by Lenin in October/November (October Revolution) and saw the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks.

[9] NEP: The so-called New Economic Policy of the Soviet authorities was launched by Lenin in 1921. It meant that private business was allowed on a small scale in order to save the country ruined by the Revolution of 1917 and the Russian Civil War. They allowed priority development of private capital and entrepreneurship. The NEP was gradually abandoned in the 1920s with the introduction of the planned economy.

[10] Struggle against religion: The 1930s was a time of anti-religion struggle in the USSR. In those years it was not safe to go to synagogue or to church. Places of worship, statues of saints, etc. were removed; rabbis, Orthodox and Roman Catholic priests disappeared behind KGB walls.

[11] Reds: Red (Soviet) Army supporting the Soviet authorities.

[12] Greens: members of the gang headed by Ataman Zeleniy (his nickname means ‘green’ in Russian).

[13] Mendele Moykher Sforim (1835-1917): Hebrew and Yiddish writer. He was born in Belarus and studied at various yeshivot in Lithuania. Mendele wrote literary and social criticism, works of popular science in Hebrew, and Hebrew and Yiddish fiction. In his writings on social and literary problems Mendele showed lively interest in the education and public life of Jews in Russia. He was preoccupied by the question of the role of Hebrew literature in molding the Jewish community. This explains why he tried to teach the sciences to the mass of Jews and to aid the people in obtaining secular education in the spirit of the Haskalah (Hebrew enlightenment). He was instrumental in the founding of modern literary Yiddish and the new realism in Hebrew style, and left his mark on the two literatures thematically as well as stylistically.

[14] Collectivization in the USSR: In the late 1920s – early 1930s private farms were liquidated and collective farms established by force on a mass scale in the USSR. Many peasants were arrested during this process. As a result of the collectivization, the number of farmers and the amount of agricultural production was greatly reduced and famine struck in the Ukraine, the Northern Caucasus, the Volga and other regions in 1932-33.

[15] Sholem Aleichem (pen name of Shalom Rabinovich (1859-1916): Yiddish author and humorist, a prolific writer of novels, stories, feuilletons, critical reviews, and poem in Yiddish, Hebrew and Russian. He also contributed regularly to Yiddish dailies and weeklies. In his writings he described the life of Jews in Russia, creating a gallery of bright characters. His creative work is an alloy of humor and lyricism, accurate psychological and details of everyday life. He founded a literary Yiddish annual called Di Yidishe Folksbibliotek (The Popular Jewish Library), with which he wanted to raise the despised Yiddish literature from its mean status and at the same time to fight authors of trash literature, who dragged Yiddish literature to the lowest popular level. The first volume was a turning point in the history of modern Yiddish literature. Sholem Aleichem died in New York in 1916. His popularity increased beyond the Yiddish-speaking public after his death. Some of his writings have been translated into most European languages and his plays and dramatic versions of his stories have been performed in many countries. The dramatic version of Tevye the Dairyman became an international hit as a musical (Fiddler on the Roof) in the 1960s.

[16] Dostoevsky, Fyodor (1821-1881): Russian novelist, journalist and short-story writer whose psychological penetration into the human soul had a profound influence on the 20th century novel. His novels anticipated many of the ideas of Nietzsche and Freud. Dostoevsky’s novels contain many autobiographical elements, but ultimately they deal with moral and philosophical issues. He presented interacting characters with contrasting views or ideas about freedom of choice, socialism, atheisms, good and evil, happiness and so forth.

[17] Pushkin, Alexandr (1799-1837): Russian poet and prose writer, among the foremost figures in Russian literature. Pushkin established the modern poetic language of Russia, using Russian history for the basis of many of his works. His masterpiece is Eugene Onegin, a novel in verse about mutually rejected love. The work also contains witty and perceptive descriptions of Russian society of the period. Pushkin died in a duel.

[18] Shevchenko T. G. (1814-1861): Ukrainian national poet and painter. His poems are an expression of love of the Ukraine, and sympathy with its people and their hard life. In his poetry Shevchenko stood up against the social and national oppression of his country. His painting initiated realism in Ukrainian art.

[19] Five percent quota: In tsarist Russia the number of Jews in higher educational institutions could not exceed 5% of the total number of students.

[20] Komsomol: Communist youth political organization created in 1918. The task of the Komsomol was to spread of the ideas of communism and involve the worker and peasant youth in building the Soviet Union. The Komsomol also aimed at giving a communist upbringing by involving the worker youth in the political struggle, supplemented by theoretical education. The Komsomol was more popular than the Communist Party because with its aim of education people could accept uninitiated young proletarians, whereas party members had to have at least a minimal political qualification.

[21] Podol: The lower section of Kiev. It has always been viewed as the Jewish region of Kiev. In tsarist Russia Jews were only allowed to live in Podol, which was the poorest part of the city. Before World War II 90% of the Jews of Kiev lived there.

[22] Mikhoels, Solomon (1890-1948) (born Vovsi): Great Soviet actor, producer and pedagogue. He worked in the Moscow State Jewish Theater (and was its art director from 1929). He directed philosophical, vivid and monumental works. Mikhoels was murdered by order of the State Security Ministry

[23] Great Patriotic War: On 22nd June 1941 at 5 o’clock in the morning Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union without declaring war. This was the beginning of the so-called Great Patriotic War. The German blitzkrieg, known as Operation Barbarossa, nearly succeeded in breaking the Soviet Union in the months that followed. Caught unprepared, the Soviet forces lost whole armies and vast quantities of equipment to the German onslaught in the first weeks of the war. By November 1941 the German army had seized the Ukrainian Republic, besieged Leningrad, the Soviet Union’s second largest city, and threatened Moscow itself. The war ended for the Soviet Union on 9th May 1945.

[24] Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact: Non-aggression pact between Germany and the Soviet Union, which became known under the name of Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Engaged in a border war with Japan in the Far East and fearing the German advance in the west, the Soviet government began secret negotiations for a non-aggression pact with Germany in 1939. In August 1939 it suddenly announced the conclusion of a Soviet-German agreement of friendship and non-aggression. The Pact contained a secret clause providing for the partition of Poland and for Soviet and German spheres of influence in Eastern Europe.

[25] Babi Yar: Babi Yar is the site of the first mass shooting of Jews that was carried out openly by fascists. On 29th and 30th September 1941 33,771 Jews were shot there by a special SS unit and Ukrainian militia men. During the Nazi occupation of Kiev between 1941 and 1943 over a 100,000 people were killed in Babi Yar, most of whom were Jewish. The Germans tried in vain to efface the traces of the mass grave in August 1943 and the Soviet public learnt about mass murder after World War II.

[26] Mandatory job assignment in the USSR: Graduates of higher educational institutions had to complete a mandatory 2-year job assignment issued by the institution from which they graduated. After finishing this assignment young people were allowed to get employment at their discretion in any town or organization.

[27] Erenburg, Ilya Grigorievich (1891-1967): Famous Russian Jewish novelist, poet and journalist who spent his early years in France. His first important novel, The Extraordinary Adventures of Julio Jurento (1922) is a satire on modern European civilization. His other novels include The Thaw (1955), a forthright piece about Stalin’s régime which gave its name to the period of relaxation of censorship after Stalin’s death.

[28] Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (JAC): formed in Kuibyshev in April 1942, the organization was meant to serve the interests of Soviet foreign policy and the Soviet military through media propaganda, as well as through personal contacts with Jews abroad, especially in Britain and the United States. The chairman of the JAC was Solomon Mikhoels, a famous actor and director of the Moscow Yiddish State Theater. A year after its establishment, the JAC was moved to Moscow and became one of the most important centers of Jewish culture and Yiddish literature until the German occupation. The JAC broadcast pro-Soviet propaganda to foreign audiences several times a week, telling them of the absence of anti-Semitism and of the great anti-Nazi efforts being made by the Soviet military. In 1948, Mikhoels was assassinated by Stalin’s secret agents, and, as part of a newly-launched official anti-Semitic campaign, the JAC was disbanded in November and most of its members arrested.

[29] Victory Day in Russia (9th May): National holiday to commemorate the defeat of Nazi Germany and the end of World War II and honor the Soviets who died in the war.

[30] Warsaw Ghetto Uprising (or April Uprising): On 19th April 1943 the Germans undertook their third deportation campaign to transport the last inhabitants of the ghetto, approximately 60,000 people, to labor camps. An armed resistance broke out in the ghetto, led by the Jewish Fighting Organization (ZOB) and the Jewish Military Union (ZZW) – all in all several hundred armed fighters. The Germans attacked with 2,000 men, tanks and artillery. The insurrectionists were on the attack for the first few days, and subsequently carried out their defense from bunkers and ruins, supported by the civilian population of the ghetto, who contributed with passive resistance. The Germans razed the Warsaw ghetto to the ground on 15th May 1943. Around 13,000 Jews perished in the Uprising, and around 50,000 were deported to Treblinka extermination camp. About 100 of the resistance fighters managed to escape from the ghetto via the sewers.