Courtesy of Natasha Bulashova from Pushchino, Russia, and Greg Cole of Knoxville, from Tennessee, USA.

A “Jewish Problem”

In the Principality of Moscow and the Russian Empire the presence of Jews was not tolerated since the Middle Ages. Jews were considered the enemy of Christ by Orthodox Christianity and believed to aim at converting Christians to Judaism. The Czars, in their role as Protectors of the Faith, regularly refused permission even for Jewish merchants to enter Russia.

When after the partitions of Poland several hundred thousand Jews become incorporated into the Russian Empire, the Russian government immediately perceives them as “the Jewish Problem,” either to be solved by enforced assimilation or expulsion.

The first “problem” the Jews pose is to the nationalist or panslavic conception of the Russian Empire. In this conception, the Jews do not fit into the aim to form “of all nationalities a single people” based on “common language, common religion and the Slavic Mir.”

The second issue is economic: the majority of Jews lives in villages and fulfills a vital role in the village economy. This poses a problem to the feudal order of the Empire, as free townspeople are not permitted to live in villages where both the land and the people – serfs – are the private property of the nobility. The Polish nobility, having lost its feudal rights after the partition, wants to regain the economic functions they once delegated to the Jews – a political demand that Russian governments are eager to accommodate.

Both issues, Jewish cultural and religious autonomy and Jewish residence in the villages, are addressed time and again by degrees and counter-degrees. However, both “problems” remain largely unresolved throughout the 19th century. Jews resist assimilation into a society that will only accept them if they renounce Judaism, and prefer their traditional village existence above forced residence in overcrowded cities.

In his “Statute Concerning the Organization of the Jews” from 1804, Alexander I is the first to formulate the dual policy of forced assimilation and expulsion from the villages. With the aim to draw the Jews into the general stream of economic and cultural life, Jews may now enter public schools for the first time. In order to undermine the Jewish village economy, Jewish residence in the villages is prohibited, and expulsions begin soon afterward. Jews are also forbidden to distill or sell alcohol to peasants, or continue leasing activities in the villages.

Life in the Pale of Settlement:

In the provinces of the Pale of Settlement, Jews form approximately one-ninth of the population. As their number increases due to the high birth rate and better medical care, the confinement to the Pale causes growing poverty. Massive expulsions from the villages, and the restrictions on professions and trade, increases competition among a growing number of people.

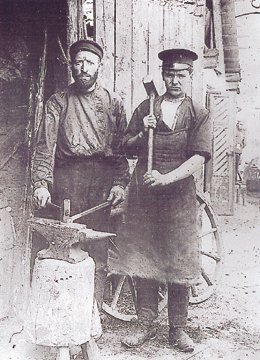

Within the Pale, the number of artisans per 1000 persons is three times higher than elsewhere. Although the government encourages Jews to engage in agriculture, the special settlements allotted for this purpose in Southern Russia cannot absorb the tens of thousands who are driven out of the villages.

During the reign of Nicholas I, the position of the Jews deteriorates significantly. To alienate them from their religion, Jews are conscripted from 1827 onward into the army for a period of no less than 25 years.

The Jewish communities are made responsible for supplying a required number of recruits (“Cantonists”) aged between 12 and 25. Kidnapping by so-called “khapers” is often necessary to fill the quota. The children are to be “re-educated,” and compulsory instruction in Christian religion and physical pressure are used to induce them to convert. In 29 years between 30,000 and 40,000 Jewish children served as “Cantonists.”

In 1843, the Jews are expelled from Kiev where they had lived for centuries. A new wave of expulsions follows when Jews are no longer allowed to live within 50 versts (1 verst = .6629 miles) of the western border.

Even government officials consider the conditions in the Pale untenable. The governor of Kiev province, where 600,000 Jews live, urges the government in 1861 to lift the residence restrictions in order to relieve the congestion in the Pale.

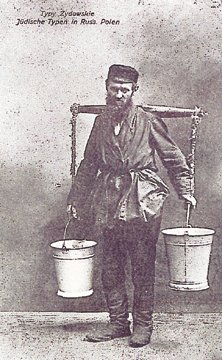

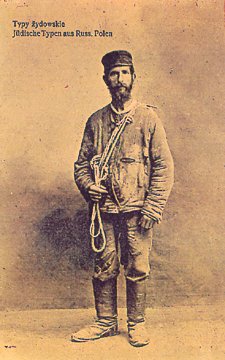

Outside the cities, the typical Jewish community in the Pale is the shtetl (mestechko), which usually has a few thousand inhabitants and is centered around the synagogue and marketplace. Jews earn their living as petty traders, middlemen, shopkeepers, peddlers and artisans, often working with woman and children as well.

Those who are no longer able to find any employment join the growing number of Luftmenshen – doing anything to earn a living. At the end of the century, the Jewish population has become so impoverished that approximately one-third depend to some degree on Jewish welfare organizations.

Although Jews are allowed to enter general schools, not many do because instruction is given in either Polish, Russian or German – not in Yiddish, which is by far the most widely spoken.

From 1844 onward, special schools for Jews are established with the purpose of bringing them “nearer to the Christians and to uproot their harmful believes which are influenced by the Talmud.” A special tax on candles is imposed to pay for them.

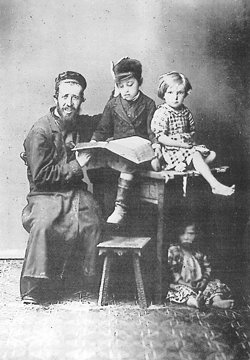

Jewish parents regard these schools with suspicion and continue to send their children to the traditional kheyder. There, the melamed (teacher) instructs the children in the Hebrew language. As the Hebrew alphabet is also used for Yiddish, the children are able to read and write in their mother tongue as well.

The number of students attending the Jewish state schools is very small: about 6000 in 1864. Some enter the mainstream of the Russian intelligentsia, and in this respect the schools fulfill their purpose. A number of these students later join the protest movement against the oppressive Czarist regime.

In spite of the difficult circumstances, Jewish cultural life develops and flourishes in the Pale. From the Pale emerges a group of writers who can be considered the founding fathers of modern secular Hebrew and Yiddish literature, and many of them become world famous.

Alexander II – a “Brief Spring”

The Reign of Alexander II brings fundamental changes for the Russian society at large, notably the emancipation of the serfs in 1861. For Russian Jews, it marks a period of great expectations now that the most oppressive measures are relaxed. On the first anniversary of Alexander’s coronation the hated Cantonist system is repealed. Bit by bit, small groups of Jews considered “useful” are allowed to settle outside the Pale: merchants, medical doctors and artisans.

The Jewish communities of St. Petersburg, Moscow and Odessa grow rapidly, and Jews start to participate in the intellectual and cultural life. The industrial development of the 1860s, following the disastrous Crimean War, creates opportunities for a small group of Jewish entrepreneurs, particularly in banking and the export trade, in mining and in the construction of railroads.

But the sudden appearance of Jewish lawyers, journalists and entrepreneurs causes a sharp reaction. After the suppression of the Polish uprising in 1863, the position of all minorities in Russia is weakened, and the movement for Jewish emancipation suffers a serious setback. Anti-Semitic agitation, expressed in newspapers like Novoye Vremya, increases after a wave of Slavophile nationalism in the 1870s. Jews are accused of forming “a state within the state” and seen as aliens trying to dominate Russia. Even the old myth of the Blood Libel, outlawed by Alexander I in 1817, is brought to life again in Kutais in 1878.

Renewed oppression – the “May Laws”

The events following the murder of Alexander II in 1881 dash all hopes the Jews might have had for further improvement of their situation. The assassination, by a small group of revolutionaries, takes place in an atmosphere of great social unrest, and the beleaguered regime falls back on a well-tried recipe: blaming the Jews.

Beginning in Elizabetgrad, a wave of pogroms spreads throughout the southwestern regions, more than 200 in 1881 alone. The authorities condone them through their inaction and indifference, sometimes even showing sympathy for the pogromists. An official investigation confirms: the plunderers were convinced that the attacks were sanctioned by the Czar himself. The same investigation blames “Jewish exploitation” as the cause for the pogroms.

With the so-called “Temporary Laws” of May 1882 a new period of anti-Jewish discrimination and severe persecution begins. It lasts until 1917. The area of the Pale of Settlement is reduced by 10 percent. Jews are once more prohibited from living in villages, to buy or rent property outside their prescribed residences, denied jobs in the civil service and forbidden to trade on Sundays and Christian holidays.

The anti-Semitic campaigns intensify after Alexander III and his family miraculously survive a railway accident in 1888. The head of the Holy Synod and the Czar’s spiritual adviser, K. Pobedonostsev, interprets this as a “sign from above” to turn away from the path of reform.

In 1887, the number of Jewish students entering secondary schools in the Pale is restricted to 10 percent. As in some towns Jews constitute 50 to 70 percent of the population, many high school classes remain half empty. In 1891 a degree is passed that the Jews of Moscow, who had settled in the city since 1865, are to be expelled. Within a few months about 20,000 people are forced to give up their homes and livelihood and deported to the already overcrowded Pale.

Alexander III dies in 1894 during a holiday in Yalta, some weeks after he had ordered the Jews from that city expelled as a precautionary measure.

The “Protocols of the Elders of Zion”

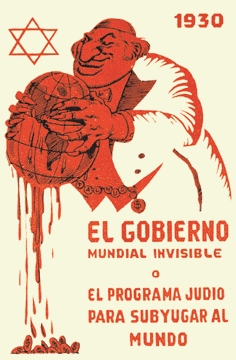

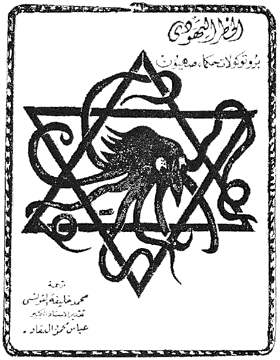

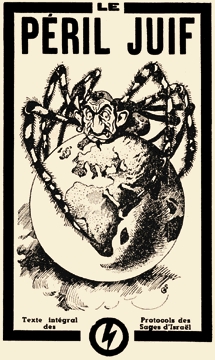

The “Protocols of the Elders of Zion” a major source for most anti-Semitic conspiracy theories to this day, were written by an anonymous author working for the Okhrana, the Russian secret police, in Paris at the end of the 19th century.

The “protocols” are said to be the minutes of a conference of Jewish leaders drawing up plans to dominate the world. In the book, the “Elders of Zion” are accused of corrupting the country by spreading liberal ideas, undermining the rightful position of the nobility, stirring up social unrest and revolution.

The “Protocols” do not immediately draw much attention when published in Russia in 1905, but this changes after the Revolution. Anti-Bolshevists point to the “Protocols” to explain the sudden and radical changes in Russia and to justify anti-Semitic violence during the Civil War. In 1921 evidence is produced that the “Protocols” are a forgery: the author has plagiarized whole sections from a French publication of 1864 which was directed against Napoleon III and had nothing to do with Jews.

The leaders of the German National Socialist Party, notably Hitler and Goebbels, refer frequently to the “Protocols.” In Hitler’s “Mein Kampf” the “Protocols” are presented as proof of an alleged “Jewish conspiracy” to dominate the world, and the persecution of Jews as a necessary self-defense.

In this way, the “Protocols” come to justify the discrimination and later the extermination of Jews by the Nazis. After the Second World War, the “Protocols” find new adherents in the Arab world by providing an “explanation” for the military victories of Israel. Today, the book continues to be distributed by Neo-Nazi and anti-Semitic groups.

The Pogroms of 1903-1906

Nicholas II, who succeeds Alexander III in 1894, makes it clear from the start that he will guard the fundamentals of autocracy with the same strictness as his father. But the movement for political reforms, freedom of speech and universal franchise has gained in strength. Successive riots of peasants, workers and students can no longer be crushed by oppression.

The government tries to deflect the revolutionary movement by initiating a war with Japan abroad, and pogroms at home. After months of violent anti-Semitic campaigns a pogrom breaks out in Kishinev in 1903. Forty-five people are murdered, and 1,300 homes and shops plundered.

For his anti-Semitic agitation, the editor of the local newspaper, Bessarabets, had received funds from the Minister of the Interior, Viacheslav Plehve. When the perpetrators of the Kishinev pogroms receive only very light sentences, it becomes clear that pogroms have now become an instrument of government policy, and Jews begin to form self-defense units.

For his anti-Semitic agitation, the editor of the local newspaper, Bessarabets, had received funds from the Minister of the Interior, Viacheslav Plehve. When the perpetrators of the Kishinev pogroms receive only very light sentences, it becomes clear that pogroms have now become an instrument of government policy, and Jews begin to form self-defense units.

During the war with Japan the anti-Semitic press blames the Jews for conspiring with the enemy. These campaigns culminate in a new wave of pogroms after the disastrous defeat of Russia. The Black Hundreds now openly declare the extermination of the Jews as their program.

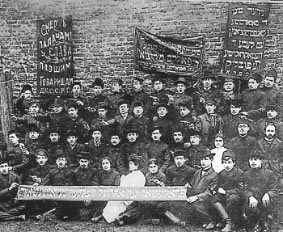

| Three pogrom victims in Odessa who were members of the self-defense organization of the Bund. During 1905-1906, more than 600 outbreaks of violence were recorded and 3,103 Jews killed. |

| Protest meeting at the funeral of Kagan, who was murdered in prison in Mosir, Belorussia, on the day of the Czar’s proclamation of the Constitution in October 1905. |

But the worst orgy of violence breaks out after the Czar is forced to grant a constitution in October 1905. Mainly organized by the monarchist Union of Russian People, and with the cooperation of local government officials, pogroms are staged in more than 300 towns and cities, leaving almost a thousand people dead and many thousands wounded. Because there is no sign of change in the Czar’s policies and as the pogroms took place with apparent approval by the authorities, a feeling of despair spreads among the Jewish communities.

A Government Blood Libel: The Beilis Affair

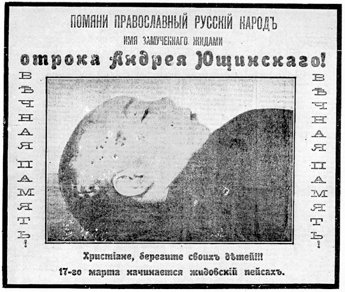

In February 1911, the liberal and socialist factions in the Third Duma introduce a proposal to abolish the Pale of Settlement. Right wing and monarchist organizations such as the Union of the Russian People and the Congress of the United Nobility react violently: they embark on a campaign to harshen anti-Jewish policies instead of lessening them. For this campaign, both organizations receive secret state subsidies from a government that has lost practically all support in parliament. When in March 1911 the body of a young Christian boy is found in Kiev, the Czarist authorities seize the opportunity to revive the age-old accusation of ritual murder. A Jewish inhabitant of Kiev, Mendel Beilis, the superintendent of a brick kiln, is arrested and charged, although by that time the authorities already know the true perpetrators.

For more than two years, Beilis remains in prison while the authorities try to build a case against him by falsifying papers and pressurizing “witnesses.” But the case backfires. In October 1913, the jury unanimously declares Beilis not guilty. The Beilis case not only draws international attention to the plight of the Jews in Russia, it also unites the conservative Octobrists and the radical Bolsheviks in their opposition to the government.

The Czarist government finds it difficult to accept this humiliating defeat. G. Zamyslovsky, one of the prosecutors in the case, repeats the accusation against Beilis in his book The Murder of Andrei Yushinsky. The book is published on the eve of the revolution in 1917 with secret funds of the Interior Ministry that have been approved by the Czar.

Political Activity and Emigration

At the end of the 19th century, the Jewish population increases to over 5 million. Russian Jews become more assimilated, and a secular Jewish culture develops, leading to greater political participation.

The early Jewish revolutionaries among the Narodniki see themselves as Russians fighting for the right of the Russian people, and believe that the Jewish problem would be solved through assimilation after the liberation of the masses. But the generally indifferent reaction, even from the liberal Russian intelligentsia, to the wave of anti-Jewish violence in 1882 is a bitter disillusion to them.

The conviction grows among Jews that the distinct economic and social discrimination targeted at them calls for the formation of a separate Jewish workers movement. In 1897, the Jewish labor movement Algemeyner Yiddisher Arbeter Bund is founded in Vilna.

The Bund advocates national and cultural autonomy for the Jews, but not in the territorial sense; it argues for a middle course between assimilation and a territorial solution. The Bund also develops trade union activities and forms self-defense organizations against pogrom violence. In 1905, it has about 33,000 members.

The question of a national territory for Jews separates the Bundists from the Zionists. After the pogroms and the May Laws of the 1880s, many Jews no longer see any point in the struggle for emancipation within Russian society and turn after the publication of Herzl’s “Der Judenstaat” in 1836 to Zionism instead. The largest Zionist party, Poalei Zion (“Workers of Zion”), founded in 1906, is Marxist in orientation and defines the establishment of a socialist-Jewish autonomous state in Palestine as its ultimate goal.

Of all the Jews active in politics, a relatively small number join the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party; most of them join the Menshevik faction after the party splits. On the eve of the Revolution, the Bolshevik party has about 23,000 members, of which 364 are Jews.

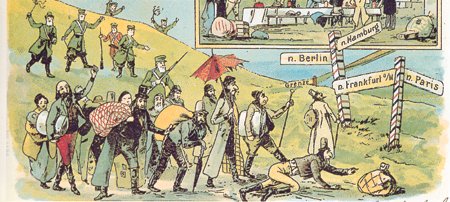

The most widespread response, though, to the continued discrimination can be found in the mass emigration of Jews to America and Western Europe. Between 1881 and 1914, more than 2 million Jews leave Russia.