(Courtesy: Blake Eskin)

A collection of Vasily Grossman’s shorter work offers a chance to reassess the Soviet master’s life and legacy. A conversation with Grossman translator Robert Chandler.

|

| Vasily Grossman in Schwerin, Germany, in 1945, with the Red Army. |

Vasily Grossman in Schwerin, Germany, in 1945, with the Red Army.

There are books one ought to read but fears one never will: too difficult, too dark, too ambitious, or just too big. Finnegans Wake, The Man Without Qualities, Gravity’s Rainbow, The Brothers Karamazov, 2666. They cannot be polished off on an intercontinental plane ride or in a weekend sprint before your monthly book-and-cocktail club; they require a semesterlong seminar, a study group, a season of solitude without home delivery of the newspaper, cable news, or Twitter. And preferably a sunny season; the most useful bit of wisdom I ever received from a professor was: Never read Dostoevsky in winter.

The same warning, I imagine, might apply to Life and Fate, Vasily Grossman’s magnum opus, about the Battle of Stalingrad, the epic seven-and-a-half-month battle that devastated a Soviet city but halted the Nazis’ progress on the Eastern Front. The book, which revolves around a Soviet Jewish nuclear scientist and his family, draws parallels between fascism and Communism and the use of mass deportation, forced labor, and murder in both totalitarian regimes. Life and Fate was the second novel about Stalingrad by Grossman, who lived from 1905 to 1964, and he worked on it for a decade before submitting it for publication in October 1960, during the thaw that followed Stalin’s death. Three months later, the KGB “arrested” Life and Fate, confiscating copies of the manuscript from Grossman, his cousins, and his typists; even the typewriter ribbons were seized. Yet Grossman remained at large, even after he appealed in a letter to Khrushchev: “There is no sense or truth in my present position, in my physical freedom while the book to which I dedicated my life is in prison.” A decade after Grossman’s death, two hidden copies of the manuscript turned up. Life and Fate was microfilmed and smuggled out to the West, where it was published in Russian in 1980.

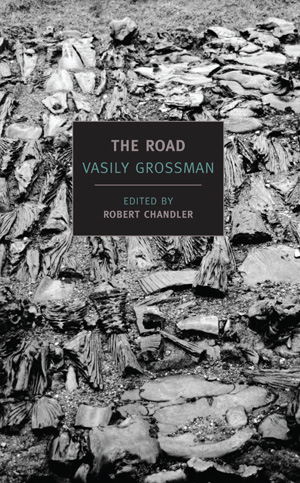

When I discovered last year that NYRB Classics had brought out Everything Flows—a much shorter, albeit unfinished, novel, which manages to tackle life in the Siberian camps, the state-orchestrated famine that killed millions in the Ukrainian countryside, and a disquisition on Lenin and human freedom into 270 pages—I was relieved to find a way to try Grossman without triggering my fear of commitment. For those who prefer even shorter works, NYRB followed up this fall with The Road, a collection that includes “In the Town of Berdichev,” a 1934 short story set in Grossman’s hometown that was his first literary success; fiction and reportage about the Holocaust, including “The Hell of Treblinka” (1944), Grossman’s pioneering reconstruction of what went on in a Nazi death camps; two letters from Grossman to his dead mother on the anniversary of her death and of the mass murder of the Jews of Berdichev; and other stories and essays. The Road appears to be a Grossman sampler, but it is full of illuminating commentary by its editor and translator Robert Chandler, who is also responsible for the recent translation of Everything Flows and for introducing English speakers to Life and Fate back in the mid-1980s.

After reading these two smaller volumes, and my e-mail exchange with Chandler (an edited version of which appears below), I feel ready to tackle Life and Fate—but I may wait until spring.

When did you first read Life and Fate? How did you come to translate it?

I first heard of Vasily Grossman nearly 30 years ago. I went to see my friend Igor Golomstock, an émigré Russian art critic. He held out a large volume—the first, Swiss-published edition of the Russian text of Life and Fate—and said, “Robert, if you want to establish yourself as a translator, you should translate this!”

In reply I simply laughed and said, “Igor, I don’t even read books as long as that in Russian, let alone translate them!”

Igor, however, is not someone easily deflected. A few weeks later he sent me the transcripts of four half-hour programs about Life and Fate that he had done for the BBC Russian Service. I read these and was gripped. I quickly discovered, as many other people have done since, that once I began reading Life and Fate—instead of just worrying about its length—I found the book surprisingly hard to put down. Grossman’s descriptions of the fighting at Stalingrad seemed extraordinarily vivid. I could sense a powerful intelligence behind the passages comparing Nazism and Stalinism. And the last letter written by the hero ‘s mother from a Jewish ghetto in Nazi-occupied Ukraine, before her death in one of the massacres that were the first stage of the Shoah, was as moving as anything I had ever read.

And so I translated one chapter for the novel, and wrote a brief accompanying article, for the excellent journal Index on Censorship. Mark Bonham-Carter, a senior consultant for what was then Collins Harvill, was also on the editorial board of Index. He contacted me and eventually commissioned a translation of the novel.

How did you return to Grossman to translate Everything Flows and the stories, journalism, essays, and letters in The Road?

I first suggested I retranslate Everything Flows long ago, but my U.K. publishers did not think there would be enough interest. Four or five years ago I realized that interest in Grossman was growing very fast indeed, and so I spoke to Harvill Secker again. This time they agreed enthusiastically. And by then I also had an excellent American publisher who was interested in Grossman: NYRB Classics.

Why retranslate Everything Flows? How is your version different from 1972 version Forever Flowing, other than the title?

Grossman is not usually thought of as a great stylist, and so people often imagine he is not difficult to translate. My own experience, however, is that his later works, at least, are very difficult to translate indeed. Whether Grossman is telling a a story or conducting an argument, his thought seldom moves in a straightforward and predictable way. It zigzags about, often taking the reader by surprise. I myself found that in early drafts I had often failed to grasp the subtlety of his thinking. The previous translator, Thomas Whitney, seems to have been unaware of this difficulty. There are pages, especially in the historical-political chapters, when his translation simply doesn’t make sense.

Had any of the material in The Road been translated into English before?

There have been previous waves of interest in Grossman. Toward the end of my work on The Road I discovered to my surprise that the 1934 story “In the Town of Berdichev” had been first translated into English as early as 1936, in John Lehmann’s journal New Writing. Most of Grossman’s wartime fiction and journalism was translated into English quite promptly. The later stories, however, have never been translated before. The only exception is “Mama,” possibly the finest of all his stories. It is based on the real-life story of an orphaned girl who was adopted by Nikolay Yezhov, the head of the NKVD at the height of the purges, and his wife Yevgenia. Rachel Polonsky translated this story almost twenty years ago and submitted it to Granta. Astonishingly, Granta rejected this terrifying story on the grounds that it was “sentimental.” It is strange how often, even though Grossman does not seem in the least avant-garde or experimental, we all seem to appreciate his greatness only after much time has passed. Rachel Polonsky, by the way, was unable to find her translation of this story—and so eventually we translated it ourselves.

You organized The Road more or less chronologically, with extensive editorial notes. It reads almost as a biography. Was that your intent?

The book took shape only gradually. The first impulse behind it was my excitement four or five years ago when I first read “Mama” and the other masterpieces Grossman composed during his last years, between the “arrest” of Life and Fate in 1961 and his death in 1964. Then I looked at what he had written during the 1930s and during the war. I realized that the Shoah was going to constitute a major theme in the book. Since Grossman was so personally involved, and since the twists and turns of official Soviet attitudes toward writing about the Shoah were so complex, it seemed important that I include some of the biographical background to his stories and articles. And then, when we settled on the title The Road, I felt it might be possible to shape the book in such a way as to give the reader an overall sense of the path Grossman followed both as a writer and as a man.

Grossman, like Isaac Babel, was a Jewish writer who reported on the Red Army from the front lines. How did Babel influence Grossman?

Babel’s Red Cavalry stories are about the Polish-Soviet War of 1919-20. Grossman’s first big success, the story “In the Town of Berdichev,” is set against the background of this same war. It is certainly influenced by Babel. There are the same elaborate metaphors; there is the same wish to startle the reader.

But Grossman also, in a way, turns Babel’s work on its head. Many of Babel’s stories are about an intellectual Jewish commissar being reluctantly initiated into a world of male violence. Grossman’s story is about a female commissar, passionately committed to the Revolution, who becomes pregnant and is reluctantly initiated into a feminine world—a world not of violence but of nurturing.

That nurturing world is also a Jewish world: Grossman’s commissar, who is neither intellectual nor Jewish, is billeted in the home of the Magazinik family. At one point, Beila Magazinik marvels at the commissar’s attention to her son: “In a word, she’s turned into a good Jewish mother.”

Does the Magazinik home resemble Grossman’s childhood home? Does Beila resemble Yekaterina Grossman?

Beila does not resemble Grossman’s mother, who was highly educated and who had lived for a couple of years in Geneva before the Revolution. The Magazanik home certainly does not resemble Grossman’s childhood home.

| In The Road, you write that there are “several scenes in Grossman’s work that show a Jewish parent-or parent figure-and a child affirming their love during the last minutes of their lives.” Yet even in “In the Town of Berdichev,” written before Grossman’s mother was killed in the Shoah, the mother-son bond seems to be a central concern. What was Yekaterina like, and how did she and her son relate to each other?I do not know a lot about her apart from what Grossman has written himself. Grossman’s stepson Fydor Guber has told me that the style and tone of “the last letter” in Life and Fate is very similar to that of letters written to Grossman by his mother.“The Old Teacher,” which describes the mass execution of Jews in, as you say in your notes, “an unnamed town that seems like a smaller Berdichev,” is remarkable for being published in late 1943.There was at that time no outright ban on mention of the mass murders of Jews, but the authorities’ preferred line was that all nationalities had suffered equally under Hitler. A frequently used slogan—all the more effective, no doubt, because of its apparent nobility—was “Do not divide the dead!” With each year it became more difficult for Soviet writers and journalists to write about the Shoah. |

Grossman’s article about Treblinka was first published as late as November 1944 and it was republished the following year, but it is unlikely that he would have been able to republish “The Old Teacher” as late as that. Any discussion of the Einsatzgruppen massacres almost inevitably raised the question of the degree of collaboration on the part of Ukrainians or citizens of the Baltic States; it was therefore easier for a Soviet journalist to write about the death camps in Poland than about the massacres on Soviet soil.

Who was the audience for “The Hell of Treblinka”? If journalism is a first draft of history, how accurate is his report? How influential was it?

The audience for his article must have been considerable. It was first published in the monthly journal Znamya (“The Banner”). It was republished in Russian as a very small hardback book and in 1945 alone it was translated into English, French, German, Hebrew, Hungarian, Romanian, and Yiddish. There were Polish and Slovenian translations in 1946. There may have been others.

With regard to the general workings of the camp, Grossman was accurate and perceptive. But with regard to the numbers of victims he made some serious errors. His biggest mistake was to estimate that around three million people were murdered in Treblinka; the true figure was probably less than 800,000.

Toward the end of “The Hell of Treblinka,” Grossman writes:

What led Hitler and his followers to construct Majdanek, Sobibor, Belzec, Auschwitz, and Treblinka is the imperialist idea of exceptionalism—of racial, national, and every other kind of exceptionalism.

Is this what Grossman really believed? Or was this necessary to say to bring it in line with Soviet ideology?

I am certain that this is absolutely what Grossman believed. And, far from being conformist, the sentence may well contain a veiled criticism of Soviet ideology, which is, after all, based on an idea of class exceptionalism.

Grossman covered World War II from the front lines—his notes and reportage have been translated and collected in A Writer at War—and beginning in 1943, worked with Ilya Ehrenburg and others on The Black Book of the Holocaust, an effort to document the Nazi campaign against the Jews. But the Soviet government halted publication of The Black Book—and destroyed the printing plates.

How, after his experience during the war, his mother’s death, his work on The Black Book and its suppression, could Grossman have denounced the Jewish doctors who supposedly plotted to kill Stalin?

There are a number of possible reasons. Most simply, he had good reason to fear for his life. And he may have thought—not entirely unreasonably—that the doctors were certain to be executed anyway and that the letter was worth signing because it affirmed that the Jewish people as a whole was innocent.

But the way you put your question, Blake, doesn’t seem quite right to me. It contains an implicit criticism, and none of us have the right to make such criticisms. Very few people survived Stalin’s regime without, at the very least, signing some such denunciation. Several years later, in Life and Fate, Grossman was to write,

But an invisible force was crushing him. He could feel its weight, its hypnotic power; it was forcing him to think as it wanted, to write as it dictated. This force was inside him; it could dissolve his will and cause his heart to stop beating. Only people who have never felt such a force themselves can be surprised that others submit to it. Those who have felt it, on the other hand, feel astonished that a man can rebel against it even for a moment—with one sudden word of anger, one timid gesture of protest.

I am also reminded of the opening chapters of Everything Flows, where Nikolay, the scientist, weighs his moral compromises and occasional noble gestures as he awaits the arrival of Ivan, his cousin who has just spent thirty years in the Gulag. Ivan will not spend a night in Nikolay’s apartment. Nikolay comes off as sympathetically as he possibly can, but Grossman and Ivan are judging him, no?

Here Grossman is almost certainly judging himself. Nikolay and his wife are in many respects modeled on Grossman and his wife. Grossman was often fiercely self-critical.

In The Road, you include two letters Grossman wrote to his dead mother on the anniversary of her murder. Were these written as private or public documents?

They were written as private documents. They are deeply moving. The memory of his mother seems to have been an extraordinary source of strength for Grossman. A passage in Life and Fate based on Grossman’s signing the letter about the Jewish doctors ends with Viktor Shtrum (who has just signed a similar letter) praying to his dead mother to help him never to show such weakness again.

In The Road, you mention a dispute over where to bury Grossman: in Novodevichye, the Moscow cemetery where many Soviet writers and intellectuals were interred, or in a Jewish cemetery. Is this argument emblematic of a larger battle over Grossman’s legacy and how Jewish it is?

You’re probably right, but there simply isn’t a great deal of interest in Grossman in Russia at the moment—so it is hard for me to talk of a “larger battle.”

I myself struggled for a long time to establish where Grossman himself wanted to be buried; I failed. Different people say different things and there is no real evidence for their assertions. But Novodevichye itself was out of the question—only the highest of the elite were buried there, and by attempting to publish Life and Fate Grossman had excluded himself from that elite.

Some who have written about Grossman—his friend the poet Semyon Lipkin and the biographers John and Carol Garrard—believe that Grossman, as you put it, “was obsessed with questions of Jewish suffering and Jewish identity” toward the end of his life. On the other hand, Simon Markish wrote in Commentary that Grossman had “the voice of a Jew, but not a Jewish voice.” What’s your view?

Once again, different people say different things. If we stay with what Grossman wrote himself, I think we can say that the theme of Jewish suffering and Jewish identity does not sound particularly strongly in Grossman’s last short stories. Several chapters of the unfinished novel Everything Flows are devoted to the “Doctors’ Plot”—the first stage in what was to have been a major purge of Soviet Jews—but no less space is devoted to the Terror Famine that led to the death of several million Ukrainian peasants.

On the other hand, we do know for sure that Grossman chose not to publish “Good Wishes,” his account of two months he spent in Armenia in late 1961, rather than agree to his editor’s demand that he omit a single ten-line paragraph about anti-Semitism. All Grossman’s friends and colleagues, including Semyon Lipkin, tried to persuade him to agree to this omission, but Grossman was intransigent. It seems likely that he was trying to atone for agreeing to sign the letter denouncing the Jewish Doctors.

How is Vasily Grossman seen in Russia today: as a Russian voice, a Jewish voice, or both? Is he esteemed more in the West or in Russia?

He is very much more highly esteemed in the West. In Putin’s Russia, he has very little by way of a natural constituency. The human rights organization Memorial sponsored a traveling exhibition about Grossman and his work. And I have heard Arseny Roginsky, chairman of Memorial, refer to Grossman with great warmth as nash pisatel—(“our writer”), but Memorial—sadly—is now a rather small organization.

By the time your English translation of Life and Fate first appeared, it had become a best-seller in France. Why? Do they have a greater taste for 800-page novels?

I imagine that this was because the question of the possible equivalence of Nazism and Stalinism was more of a live issue in a country that still—in the early 1980s—had a strong Communist Party. Now, however, I think Grossman is at least as well known in the English-speaking world as he is in France.

Was Grossman an influence on Claude Lanzmann?

I wish I knew! All I can say is that there is no mention of Grossman in Shoah.

In his essays and in his fiction, Grossman expounds almost like a moral philosopher. What is the basis of his morality: His upbringing? His socialist ideals? Witnessing the devastation of war and the Shoah? Tolstoy and other literature? Some combination?

Grossman behaved with great courage in the late 1930s, at the time of the Great Terror, so I don’t think it is primarily a matter of his witnessing the war or the Shoah. His parents were involved with the revolutionary movement, and Grossman was certainly brought up with socialist ideals. The moral courage shown both by the Russian Populists and by such writers as Tolstoy and Chekhov remained important to Grossman until the end of his life.

Of the remaining writings left untranslated, what should be next to fill out our literary understanding of Grossman? Our understanding of Grossman’s Jewish consciousness?

I’m hoping to start work soon on Good Wishes, his travel sketch about Armenia. This is by far the most personal, the most intimate, of Grossman’s works. Although all the many different threads are very deftly woven together, it has an air of absolute spontaneity, as though Grossman is just chatting to the reader about his impressions of Armenia, his various planned and unplanned meetings, and even his physical problems. Grossman did not know this at the time, but he was probably already suffering from cancer.

And after Good Wishes, I hope to translate For a Just Cause. I am ashamed to say that I only recently read this “prequel” to Life and Fate for the first time. There are a number of somewhat dull historico-political chapters, but much of the novel—the chapters about the lives of the Shaposhnikov sisters and the descriptions of the fighting at Stalingrad and elsewhere—is in no way inferior to Life and Fate.

Soviet authorities destroyed the printing plates of The Black Book and “arrested” the manuscript of Life and Fate. Which of these was a bigger blow to Grossman?

There are many accounts of how deeply upset Grossman was by the “arrest” of Life and Fate. He himself said, “They strangled me in a dark corner.” But I have not been able to find any account at all of Grossman’s feelings after the destruction of the plates of The Black Book. All I can say is that what must surely have been a terrible blow did not prevent him from working. He seems simply to have carried on as if nothing much had happened, continuing with his work on For a Just Cause.

Imagine that when Grossman submitted the manuscript of Life and Fate in 1961, it had been published instead of suppressed. Unlikely, I know, but Solzhenitsyn was able to publish One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich the following year. How would Grossman’s life have been different? His literary reputation? Our understanding of the Soviet Union?

Now you’re asking me to write a novel even longer than Grossman’s! I would like to think that Grossman would have at once become as famous as Solzhenitsyn and that we would have understood many things about the Soviet Union a lot sooner. But who knows? Everything Flows was published in 1972 and no one paid any attention at all. Even Life and Fate did not receive a great deal of attention when my translation was first published in 1985.