(by Vasily Grossman)

Translated by Robert Chandler

Review by Nancy Sherman

In Life and Fate, Vasily Grossman’s 1960 novel about the Battle of Stalingrad, dozens of characters are linked to one man, Viktor Pavlovich Strum, a high-ranking Jewish physicist. Early in this book of nearly 900 pages, Viktor’s mother, Anna Semyonova, writes to him from behind barbed wire in the Jewish ghetto where she awaits her death. The brief, passionate letter stands out like a single note amid the cacophony of war:

“When you were a child, you used to run to me for protection. Now, in moments of weakness, I want to hide my head on your knees; I want you to be strong and wise; I want you to protect and defend me. I’m not always strong in spirit, Vitya – I can be weak too. I often think about suicide, but something holds me back – some weakness, or strength, or irrational hope.”

Anna’s letter was staged recently as a dramatic monologue in Paris and in New York and recorded on film by veteran filmmaker Frederick Wiseman. It’s a letter for the ages, and the massive narrative that surrounds it is equally stirring. The book’s recent reissue by Harvill Press is an important literary event, coming as it does at a time when the struggle for freedom in the midst of oppressive ideologies is evident worldwide.

Vasily Grossman was born in 1905 in Berdichev, Ukraine. He moved to Moscow in his twenties, where he became the protege of Maxim Gorky and began publishing novels and short stories. During the Second World War, Grossman worked for Red Star, the leading Soviet army newspaper, and in his role as reporter witnessed the siege of Stalingrad and the capture of Berlin. Grossman also reported on the Holocaust and its aftermath, and he became increasingly aware of his own Jewish roots.

|  |

Until 1955 Grossman’s status within the Soviet literary establishments appears to have been essentially secure, despite occasional political and anti-Semitic attacks. But the text of Life and Fate, completed in 1960, was considered blatantly anti-Soviet. The original manuscript was confiscated by KGB officers in 1961. Though it resurfaced in the West some twenty years later, smuggled out on microfilm, Grossman died in 1964 without having seen it published.

Life and Fate is a great novel of twentieth-century history, but it’s not a modern novel. With no apparent irony, Grossman wrote this exposé of the Soviet regime in a style faithful to the reigning literary fashion of Socialist realism. The outlook too is distinctly that of the nineteenth century: discrete human beings are firmly linked to each other by birth and circumstance, by their absolute values and actions or by the lack thereof; no one is isolated except in death. Personal ambiguity is not an option; people live or die by their beliefs.

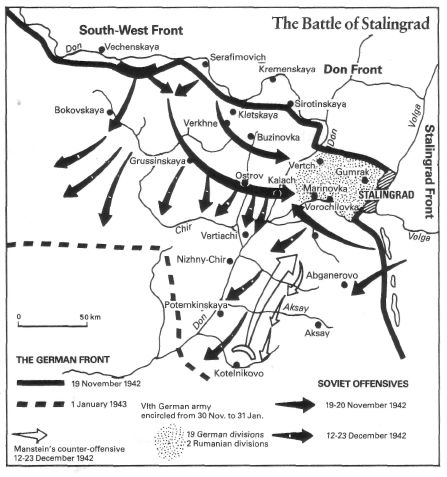

Grossman portrays not only the sweeping effects of Nazism and Soviet Communism, but the ways in which these crushing ideologies daily affected individuals – fathers, mothers, children, lovers, friends. Structurally, the book shifts between several settings: the laboratories and institutes where Viktor works; a German prisoner-of-war camp; a Russian labor camp for dissidents; battalion headquarters; in a cattle car en route to the gas chambers; in the prison where political criminals are interrogated. All along the chaotic, bloody Russian front, the deployment of men and weapons, the deadliness of hunger and siege, and the cruelty, accident, and error that underlie military strategy take their horrifying toll.

In contrast, the novel’s desperate characters seek safety and solace in kitchens, overcrowded flats, and in the bombed-out cellars of the blasted countryside. Several subplots wind around the central story of Viktor, a senior member of the Soviet science community whose status becomes precarious because of rising anti-Semitism and because of his unpopular convictions about the future of Soviet research. He is an internationalist, a progressive rationalist, seeing science — and nuclear physics in particular — as a universal rather than a political endeavor.

In a stunning scene toward the end of the book, after Viktor has been denounced publicly by his former colleagues, the telephone rings in his cold Moscow flat. It is Stalin himself, wishing Viktor success in his work. Stalin’s endorsement means not only that Viktor’s career has been saved, but that research leading to the creation of deadly nuclear weapons has been sanctioned by the State: “It was a long way from the desks of a few dozen physicists, from sheets of paper covered with alphas, betas, gammas, ksis and sigmas, from laboratories and library shelves to the cosmic and satanic force that was to become the scepter of State power. Nevertheless, the journey had been begun; the mute shadow was thickening, slowly turning into a darkness that could envelop both Moscow and New York.”

Despite the pessimism implicit in a book about the ravages of war and totalitarianism, the novel ends with a description of the birth of spring. It’s a coda reminiscent of the agrarian optimism of many nineteenth-century Russian novels. A man and woman walk to the market, first along a path where “the glitter of the snow, the water and the ice on the puddles was quite blinding. There was so much light, it was so intense, that they seemed almost to have to force their way through it.” Then they enter a forest, in whose dark silence they “hear both a lament for the dead and the furious joy of life itself.” With this final contrast, Grossman offers a philosopher’s vision of Life and Fate mediated by nature and driven by the unstoppable flow of time.

Selected Passages

They say that children are our own future, but how can one say that of these children? They aren’t going to become musicians, cobblers, or tailors. Last night I saw very clearly how this whole noisy world of bearded, anxious fathers and querulous grandmothers who bake honey-cakes and goose-necks – this whole world of marriage customs, proverbial sayings and Sabbaths will disappear forever under the earth. After the war life will begin to stir once again, but we won’t be here, we will have vanished – just as the Aztecs once vanished. (page 92)

It was early in the evening, very quiet, and the air was extraordinarily transparent; even the smallest objects were clearly and distinctly visible. The smoke rose vertically from the chimneys. Logs crackled in the field-kitchens. A girl was embracing a dark-haired soldier in the middle of the street, her head on his chest, weeping. Boxes, suitcases and typewriters in black cases were being carried out of the buildings that had served as their HQ. Signalers were reeling in the thick black cables that stretched between corps headquarters and the headquarters of each brigade. A tank behind the barns backfired and let out puffs of exhaust smoke as it prepared to set off. Drivers were filling the petrol tanks of their new Ford trucks and removing the thick covers from their radiators. Meanwhile, the rest of the world was perfectly still.

Novikov stood on the porch and looked round; for a moment all his cares and anxieties fell away. Soon afterwards he set out in his jeep on the road to the station.

The tanks were coming out of the forest. The ground, already hardened by the first frosts, rang beneath the unaccustomed weight. The evening sun lit up the crowns of the distant firs where Karpov’s brigade was slowly emerging. Makarov’s brigade was passing through some young birch trees. The soldiers had decorated their tanks with branches; the pine needles and birch leaves seemed as much a part of the tanks as the armour plating, the roar of the motors and the silvery click of their tracks.

When old soldiers see reserves being moved up to the front, they say, “It looks like a wedding.” (pages 227-228)

A voice unbelievably similar to the voice that had addressed the nation, the army, the entire world on 3 July 1941, now addressed a solitary individual holding a telephone receiver.

“Good day, comrade Shtrum.”

At that moment everything came together in a jumble of half-formed thoughts and feelings – triumph, a sense of weakness, fear that all this might just be some maniac playing a trick on him, pages of closely written manuscript, that endless questionnaire, the Lubyanka…

Viktor knew that his fate was now being settled. He also had a vague sense of loss, as though he had lost something peculiarly dear to him, something touching and good.

“Good day, Iosif Vissarionovich,” he said, astonished to hear himself pronouncing such unimaginable words on the telephone.

The conversation lasted two or three minutes.

“I think you’re working in a very interesting field,” said Stalin.

His voice was slow and gutteral and he placed a particularly heavy stress on certain syllables; it was so similar to the voice Viktor had heard on the radio that it sounded almost like an impersonation. It was like Viktor’s imitation of Stalin when he was playing the fool at home. It was just as everyone who had ever heard Stalin speak – at a conference or during a private interview – had always described it.

Perhaps it really was a hoax after all?

“I believe in my work,” said Viktor.

Stalin was silent for a moment. He seemed to be thinking over what Viktor had said.

“Has war made it difficult for you to obtain foreign research reports?” asked Stalin. “And do you have all the necessary laboratory equipment?”

With a sincerity that he himself found astonishing, Viktor said: “Thank you very much, Iosif Vissarionovich. My working conditions are perfectly satisfactory.”

Lyudmila was still standing up, as though Stalin could see her. Viktor motioned to her to sit down. Stalin was silent again, thinking over what Viktor had said.

“Goodbye, comrade Shtrum, I wish you success in your work.”

“Goodbye, comrade Stalin.”

He put down the phone. (pages 762-763)