Playing soccer with the Nazis

(Courtesy: Tony Taylor)

Soccer games can end in disappointment, but seldom in real tragedy. In 1941, however, a game ended with a score line that was almost guaranteed to lead to tragedy and death. So what really did happen on that hot August day, and why? And why has the game become etched in the memory of so many people? Tony Taylor combined his passion for soccer with his skills as an historian to bring us some answers. It’s a dramatic and spell-binding story.

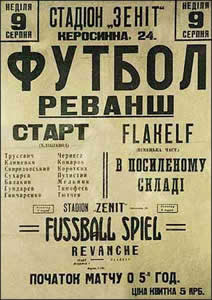

That mid-afternoon of Sunday August 9th 1942 was hot in Kiev. Thousands of soccer fans, some in shabby civilian clothes but many of them in German military uniform, headed for the Zenit Stadium. The kick-off was 5 o’clock, a delayed start because of the summer heat. Soon, the temperature began to fall, and, in the packed stadium, an eager crowd waited for the two teams to appear. The Ukrainian home side ran out in their dark red shirts and white shorts, the team colours of Russia’s national soccer team. The visitors appeared in white shirts and black shorts, the strip of the German national side.

The whistle blew. The game was under way and the match was fiercely contested. The home team won convincingly. The Ukrainian supporters went wild. The Germans glowered.

The celebrations were brief. Over the next few weeks, most of the home players were arrested and taken to Gestapo headquarters in the city centre. There they were interrogated and tortured before being taken to a concentration camp on the outskirts of the city. Three were eventually shot dead. Within a matter of months, four of the victorious Ukrainian players had died at the hands of the Nazis. By the war’s end in 1945, there were few known survivors of what became known as the Game of Death.

But the story of the Game of Death did not start on that fateful day in August. The origin of the game between the players who represented Nazism and the players who stood for Ukrainian Communism goes right back to the 1930s and the reign of terror that the people of the Soviet Union suffered under Joseph Stalin.

The Great Terror

In the 1930s, the people of Ukraine(1) suffered terribly under Stalin, the Soviet Russian dictator. Stalin had a paranoid suspicion of almost everything and a hatred of Ukrainian difference from the rest of Russia. He feared the possibility of a Ukrainian breakaway from his massive Communist empire, so particular attention was given to suppressing Ukrainian nationalism. Stalin’s government terrorised the Ukraine with a special ferocity.

In the early 1930s, Stalin’s repressive farming policy produced the Great Hunger, a famine in Ukraine, which eventually led to the deaths of about 14 million people. As if that were not enough, in 1937 Stalin began a policy of political repression, the Great Terror, which affected all the Soviet republics. In Ukraine, it led to the executions of the Ukrainian government officials and the deaths of approximately 170,000 victims in secret police purges (2). Night arrests by the NKVD (3)followed by torture and execution were common. If you were fortunate, you were sentenced to transportation and disappearance into the Siberian Gulag (4). If you were not, you were lined up against a wall and shot, or, as a variation, you knelt down and got a bullet in the back of the head from an automatic pistol.

The ‘crimes’ that led to these arrests are very strange in our eyes. A simple accusation of being bourgeois (5) by a relative or by a neighbour was all it took to be ‘disappeared’. Teachers were denounced by students for not following the Communist Party line. Factory workers who arrived twenty minutes late for work could be arrested and deported. Speaking to a foreigner was yet another crime. By 1939, the Stalinist government was feared and hated by ordinary Ukrainians, as the whole of Soviet Russia, including Ukraine, was in the grip of a reign of constant terror that affected every part of life, including soccer.

Soccer had become very popular in Russia in the 1930s. For many Soviet citizens, it was a relief to be able to go to a football match (6)and temporarily lose themselves in the game, getting away from the fear of arrest and deportation. In the capital, Moscow, a massive new soccer stadium was built in the Luzhniki district. The best-known Russian teams were Moscow Spartak and Moscow Dynamo. But even in football it was impossible to escape the politics. Spartak was named after German Communist revolutionaries. Dynamo was funded by the trade unions, the secret police and the Red Army. In Soviet Russia, soccer was a state-sponsored activity.

Ukraine too had its own crack side, Dynamo Kiev. The rivalry between teams in the two cities of Moscow and Kiev was intense, mainly because of the ethnic differences between Russians and Ukrainians. In 1938 Dynamo Kiev came fourth in the national league, scoring seventy-six goals but then came a dip in their fortunes as they performed poorly in 1939 and 1940. In 1941, Kiev fans, looked forward to seeing their team play in the new Republic Sports Stadium, but they were not expecting a great turnaround in fortune in that season, which, as it happened only lasted four games.

The season was so short because Nazi armies invaded the Soviet Union at 3 am on 22nd June 1941. This was the first move in Hitler’s long-planned invasion of the Soviet Union, named Operation Barbarossa (7)

Map of Operation Barbarossa

The Soviet forces, weakened by Stalin’s purges and hampered by the dictator’s belief that the German invasion was a trick were unprepared for the invasion. The Red Army collapsed under the massive force of Operation Barbarossa. The Soviet airforce was all but wiped out and the Nazi forces advanced deep into Soviet territory in a three-pronged attack. One of their main thrusts was south, towards Kiev. To help defend their nation, several Dynamo Kiev players joined the military and went off to fight. As the Germans approached Kiev, the others who had stayed behind helped out with civil defence in the city. But it was no good. On 19th September, three months after the start of the Barbarossa campaign, Kiev fell to the Nazis after a bitter struggle through the streets of the city.

Hitler was triumphant. Kiev, one of the Soviet Union’s major cities, was captured. At the same time, to the north, German troops were heading for the outer suburbs of Moscow and, further north again, racing towards Leningrad.

Life Under the Nazi Jackboot

In Kiev itself, there was a period of uncertainty and panic following the Red Army’s scorched earth (8) destruction of factories and warehouses.

View of the destruction of Kiev

Several of the players of Dynamo Kiev who had survived the onslaught found themselves prisoners of war. The camps in which they were being held were little more than barbed wire enclosures in which hundreds of thousands of Soviet prisoners eventually starved to death or died from disease. The Dynamo players who returned to the Kiev camps were the lucky ones. In World War Two, the German attitude to Soviet prisoners was one of murder by neglect.

Russian prisoners of war marching to German captivity late in 1941.

An estimated one in six of 5.5 million Russian PoWs survived the war.

Back in Kiev, another murderous activity was taking place. On 29th September all Jews from the city were ordered by the Germans to report to a central venue with their luggage and valuables. Those who disobeyed would be shot on sight if discovered. This Aktion (9) led to the murder of 33, 771 Jewish men, women and children in just two days, Monday 29th September and Tuesday 30th September. They were killed at a ravine just outside the city called Babi Yar (10). That ravine was to see the murders of hundreds of thousands more Jews and non-Jewish Russians and Ukrainians over the next year.

Jews marching on their way out of the city of Kiev to the Babi Yar ravine to be murdered pass corpses lying on the street. Photo credits: Yelena Brusilovsky Collection, courtesy of USHMM Photo Archives |

However, in the first year of the Nazi occupation, despite the horrors of war, there was still a possibility that the Ukrainians could have become allies of the Germans. Many of them hated Stalin more than they hated Hitler and there was a strong anti-Jewish feeling amongst some Ukrainian nationalists. These nationalists looked forward to an improvement in their lives under the Nazis, and possibly even an independent Ukraine. A group of Ukrainians marched through the city streets in a possibly staged demonstration carrying a large banner of the Fuhrer with the legend ‘Hitler Liberator’ carefully printed at the bottom.

Yet, in the months that followed the fall of Kiev, brutal treatment by the German authorities of the inhabitants of the ruined city meant that they were forced to struggle desperately for survival. And there were treacherous Ukrainian informers at large. These were the despised collaborators who worked closely with the Nazis in seeking out former Soviet officials and Jews. Some Ukrainians even volunteered to be part of the Nazi killing apparatus either as concentration camp guards or as members of SS death squads. The Nazi occupation led to mass arrests, confessions extorted by torture, reprisals and summary executions. By the end of November 1941 an estimated 100,000 Ukrainians had been murdered, including 75,000 Jews and 25,000 non-Jews. To many Ukrainians, life under the Nazis seemed just as bad as it had been under the Stalinist regime, if not worse. And, because of food shortages, those who managed to keep out of the way of the Gestapo informers had to stay alive by eating domestic pets and even pigeons and rats. By the end of 1942, following tens of thousands more arrests and shootings, most of the inhabitants of Kiev hated the Nazis as much as they had hated the NKVD.

But the citizens of Kiev still loved their football. And some of the luckier Dynamo Kiev players had found their way back to the city as released prisoners of war.

Bakery Number 3

It was at Kiev’s huge Bakery Number 3 that the players eventually gathered to look for work in occupied Kiev. It all started when Nikolai Trusevich, Dynamo’s huge goalkeeper returned to the city.

Gaunt and bedraggled after his experiences as a prisoner of war, Trusevich, was given a job as a sweeper in the bakery by Iosif Kordik, a Dynamo fan. Kordik was the bakery’s new manager, who held his privileged position there because of his German origins. The bakery became a shelter for Trusevich who had been released with thousands of other Russian prisoners-of-war. Their freedom was an illusion though; the POWs had been let go with no permits to have a job or to live in an apartment. Effectively the Germans were operating a policy of death by starvation and hypothermia.

Kordik, a sports enthusiast, then hit on the idea of setting up a bakery football team and, in the European spring of 1942, Trusevich began a search of the streets of Kiev, looking for former team mates. His first find was the tricky winger Makar Goncharenko. Goncharenko remembers the invitation:

Kolya came to me at Kreschatick Street where I was living illegally at my former mother-in-law’s house. He came to me to have a chat about this idea and to find some of the other boys. We got in touch with Kuzmenko (striker) and Sviridovsky and they contacted some of the others.

Over the next few weeks, players from Dynamo as well as from the former Lokomotiv Kiev team, drifted towards the bakery where they found work, food and shelter. But, in a city where the Germans and their Ukrainian helpers ruled with murderous efficiency life in the bakery was still far from safe, as Goncharenko remembers:

Nevertheless, despite the constant presence of torture and death, Trusevich, the genial giant of a goalkeeper, was determined to set up a team. He called it FC Start (Football Club Start), possibly as recognition of a new beginning. On June 7th 1942, FC Start, with its former Dynamo and Lokomotiv stars, played its first game in the local league. The league was run by a Quisling Georgi Shvetsov, a former footballer and sports instructor and Start’s first opponents were Rukh, Shvetsov’s pet team.

The FC Start players, under-nourished, and tired from twenty-four hours shifts at the bakery, were clad in cut-down trousers instead of shorts, work boots or canvas shoes instead of proper football boots and they wore old, threadbare shirts. Rukh’s players were better fed, more rested and wore regular soccer kit.

FC Start won 7-2. Shvetsov was humiliated and he was furious. He immediately went to the German commandant and asked that FC Start be banned from training at their stadium.

FC Start’s first and last season – summer 1942

Despite the training ban, Trusevich’s team went on to a winning streak that summer. They beat a Hungarian garrison team 6-2. Then a cheerfully carefree Romanian side was thrashed 11-0. The winning sequence began to have an effect on the morale of the oppressed people of Kiev who were soon willing to pay five roubles a game to see their favourites crush the opposition. This was a price well worth paying, especially if the opposing team came from the regiments of the occupying powers.

Things started to get serious though when FC Start hammered six goals without reply past PGS, a German military team, on Friday July 17th. The game was played in a fair spirit but the German authorities were becoming alarmed at the spectacle of the ‘master race’ and its allies being humbled by a bunch of ‘sub-human’ Ukrainians. Things went from bad to worse for the occupiers when FC Start destroyed a fancied Hungarian outfit, MSG Wal 5-1 on the Sunday immediately following the Friday they had put six goals past PGS. Eleven goals in two games! FC Start won the re-match against MSG Wal a week later, 3-2. The Ukrainian team was on a roll. The German authorities could stand it no longer. They stepped in.

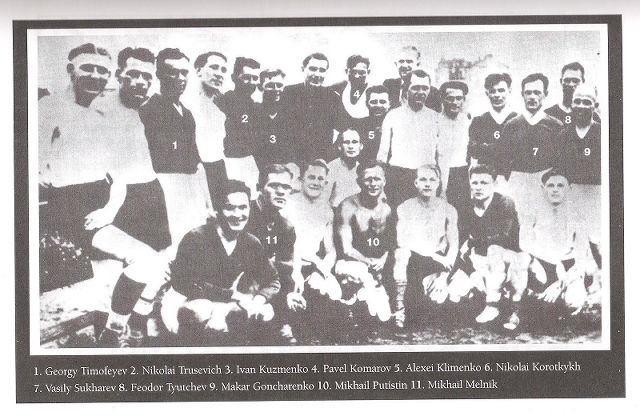

Cover photo from Andy Dougan’s book Dynamo

Copyright permission has been sought for this image

The book gives a very detailed account of the Game of Death. The origins of this newspaper photo are not clear but we do know that Dougan hired a local from Kiev to look through the archives and the newspaper records of that time. The photo was taken after the game with PGS (white shirts) on July 17th. Players featured include Kuzmenko (back row far left). Goncharenko, the tricky winger is far right, middle row, with receding hairline. Trusevitch is on the original photo but off this cropped picture, standing well to the left and grinning. In post-war Soviet Ukraine, a photo of Ukrainian players standing alongside German players would have been enough to send the surviving Ukrainians off to Siberia for collaboration with the Fascist enemy.

On the very Sunday afternoon that FC Start were hanging on to their narrow 3-2 lead against MSG Wal, in a different stadium in Kiev, the Ukrainian nationalist team Rukh faced Flakelf, a newly-formed German Luftwaffe side. Rukh lost badly. Flakelf, it was rumoured, had never lost a game and the match against Rukh was just a training exercise, it was suggested. Training for what, was the question? The answer soon came.

On Thursday 6th August a match was arranged between Flakelf and FC Start. The Germans and the Ukrainian nationalists expected an easy victory for the Luftwaffe side. To their fury, FC Start won convincingly and easily, despite brutal fouls by a Flakelf team determined to put FC Start off their game. The final score was 5-1.

Unusually, but unsurprisingly, there were no reports of that particular game in the German-controlled Kiev newspapers the next day. Within twenty-four hours of the final whistle though, official posters began to appear all over Kiev announcing a re-match, fixed for Sunday August 9th. This time, the Germans would be better prepared.

The Game of Death Sunday August 9th 1942

|  |

| FC Stary Team | Flakelf (German) Team |

Crowd control at the Zenit stadium was in keeping with the tense atmosphere. Armed Nazi guards and their German Shepherd dogs patrolled the touchline. Ukrainian police kept the civilian crowd back by waving pick-axe handles. The German spectators and their Ukrainian sympathisers had the seats in the grandstand. The Ukrainian supporters made do with the grassed edges of the football pitch.

As the Ukrainian players were getting ready in the FC Start dressing room, an SS officer entered unannounced. According to Goncharenko, he addressed the team in perfect Russian:

I am the referee of today’s game. I know you are a very good team. Please follow the rules, do not break any of the rules, and before the game, greet your opponents in our fashion.

Goncharenko knew immediately what this meant. They had a Nazi fanatic as referee. And FC Start were expected to give the Nazi salute before the start of the game. After the SS man left, there was pandemonium in the dressing room. Some players wanted to pull out altogether. Others wanted to play hard and win hard. A Rukh player, who was a ring-in for FC Start, suggested it was best if they throw the match. Meanwhile a Rumanian delegation appeared with followers and fruit and wished FC Start good luck. Other visitors just brought their advice, which was mainly along the lines of deliberately losing the match. In all this hubbub, the team decided to just go out there and play football.

The minutes before kick-off did little to reduce the tension. The burly and well-fed Flakelf team lined up and gave the Nazi salute. ‘Heil Hitler!’ they chorused. The German spectators roared approval. The FC Start players stood with heads down. It was their turn. They slowly raised their arms. It looked as if they were going along with their instructions from the ‘referee’. But instead of giving a Nazi salute, the FC Start players brought their arms back to their chests and, in unison, shouted a Soviet slogan, ‘FizcultHura!’ (Physical Culture Hooray!)

The chant was a public rejection of the Nazi regime. To make matters worse ‘Hurrah!’ was the battle cry of Red Army soldiers, a sound that the German soldiers present would have known only too well.

Then the game began.

Just as the FC Start players forecast, the Nazi referee ignored Flakelf fouls and the German team quickly targeted Trusevich, the goalkeeper who, after a sustained campaign of physical challenges, was kicked in the head by a Flakelf forward and left groggy. While Trusevich was recovering, Flakelf went one goal up.

The referee continued to ignore FC Start appeals against their opponents’ violence. The Flakelf team went on with their war of intimidation using all the tactics of a dirty team, going for the man not the ball, shirt-holding, and tackling from behind, as well as going over the ball. Despite this FC Start scored with a long shot from a free kick by Kuzmenko. Then Goncharenko, against the run of play, dribbled the ball around almost the entire Flakelf defence and tapped it into in the German net. 2-1! By half-time, FC Start were yet another goal up.

In the jubilant FC Start dressing room, the team received two unwanted visitors. The collaborator Shvetsov turned up and told them that it would be in their best interests to protect themselves. He left. Shvetsov was then followed by yet another SS officer. This SS man explained calmly and politely, again in perfect Russian, that although the Ukrainians had played very well in the first half, there was no way they could win the game. They should be aware of the consequences of their actions, he said. He turned and left.

The second half was almost an anti-climax. The Flakelf players seemed to be terrified of the Ukrainian fans and were far less physical. Each side scored twice. Towards the end of the match, with FC Start in an almost unbeatable position at 5-3, Klimenko, a defender, got the ball, beat the entire German rearguard and walked around the German goalkeeper. Then, instead of letting it cross the goal line, he turned around and kicked the ball back towards the centre circle.

It was total humiliation for Flakelf. An FC Start defender choosing not to score against them. The SS referee blew the final whistle before the ninety minutes were up.

The Aftermath

There was no celebration by the FC Start players as they left the pitch. In the stadium they could see and hear the pandemonium. Guard dogs were let loose on the Ukrainian crowd, as braver souls pushed and jeered at the German dignitaries hurriedly leaving the grandstand.

Revenge came slowly. The Germans counted up the damage. Their Aryan team had been embarrassed by a bunch of ‘sub-humans’. The people of Kiev had loudly and publicly shown their contempt for their Nazi oppressors. The Nazi’s Hungarian and Romanian allies seemed to have sided with the ‘enemy’.

In modern terms, it was a public relations disaster and somebody was going to pay. But not on that Sunday. Any violence against the players on that day would probably have led to a revolt by the people of Kiev. The Germans could have crushed such a rebellion without too much difficulty but there would have to be some difficult explaining to do to the higher authorities in Berlin.

Almost as if nothing much had happened, there was one more fixture to play, on August 16th, against the nationalist team Rukh. FC Start continued their winning streak. They beat Rukh 8-0.

Following that match, the Gestapo turned up at Bakery Number 3 with a list of players. Each named player at the bakery was arrested and driven to the secret police HQ in Korolenko Street. There they were interrogated under torture. The Gestapo wanted them to confess to being criminals or saboteurs. That way, they could be shot with some official justification.

None of them cracked. But Nikolai Korotkykh, one of the players, was exposed as a former NKVD officer by his sister and was tortured to death by the Gestapo in Korolenko Street. He was the first fatal casualty of the Game of Death.

Unable to break the players’ resistance, the Gestapo sent the ten survivors off to a nearby labour camp at Siretz. Here the inmates were expected to work until they died of starvation, dehydration, disease or hypothermia. Prisoners at Siretz were subjected to the kinds of cruelties that sadistic prison guards were notorious for in the German labour camp system – beatings, shootings, hangings, burnings alive and fatal savagings by guard dogs.

The Fate of the Players

In the camp, the FC Start players struggled to survive in their different ways.

One, Pavel Komarov, was suspected of turning informant and he appears to have been allowed to escape the camp in 1943 as the Red Army returned to capture Kiev. He disappeared from view.

As for the others, in February 1943, following an attack by anti-German partisans, the camp commandant decided to shoot every third prisoner as reprisal. The entire camp was lined up in the freezing mid-winter cold. Kuzmenko, the FC Start striker and scorer from the free kick, was one of those clubbed to the ground and shot dead. Young Klimenko, who had declined the opportunity to score in the famous match, was next. He was clubbed down and shot behind the ear as he lay on the ground. Trusevich the giant goalkeeper and captain was also knocked to the ground. According to an eyewitness, he sprang back to his feet and shouted out a Communist slogan ‘Red Sport will never die!’ A German guard opened fire. Trusevitch reportedly died on his feet, wearing his goalkeeper’s jersey. The bodies of the three players, along with those of all the other murdered prisoners, were taken to Babi Yar and thrown into the ravine.

Three of the other players, Goncharenko, Tyutchev and Sviridovsky, who, fortunately, were in a work squad in the city, were shocked when the news filtered through. They guessed that, because of their profile as FC Start players, it might be their turn next. All three quickly made the decision to escape and they stayed hidden in the city until Kiev was liberated from German occupation in November 1943.

|

| Goncharenko and Sviridovsky in front of the Memorial reminding the Heroes of the FC Start Team |

Not that surviving the horrors of the camp at Siretz was any great relief for Goncharenko and company. As soon as Stalin re-asserted his control over occupied parts of the Soviet Union, those who had come into contact with the Germans were rigorously interrogated by the newly-formed MVD (successor to the NKVD). The Stalinist version of totalitarianism was back.

Finally, of the Lokomotiv players who joined the FC Start team for the Game of Death, nothing is known. They disappeared completely in the wartime chaos.

Questions about myth and history

There are at least three sets of questions that need to be answered about this story.

The first question is about the story as a long-lasting myth. Maybe there are some signposts in the next paragraph or two.

The Game of Death story became an ‘unofficial’ myth in the immediate post-war years, and, as is often the case, the myth was not the same as reality. As recently as 1997, in his book Football in Sun and Shadow, Uruguayan journalist Eduardo Galeano told the mythic story as follows:

During the German occupation they (Dynamo Kiev) committed the insane act of defeating Hitler’s squad in the local stadium. Having been warned, ‘If you win, you die.’ they started out resigned to losing, trembling with fear and hunger, but in the end they could not resist the temptation of dignity. When the game was over all eleven were shot with their shirts on at the edge of a cliff.

Galeano’s version is one believed by many and is a variation of the unofficial myth that came out of the events in Kiev. The question here is how come the myth lasted so long?

At first the Soviet authorities had recognised no myth about FC Start. This was in spite of the apparent heroism of the players in 1942 and despite the Ukrainian view of the important part FC Start had played in maintaining morale amongst local people under Nazi occupation. The post-war Stalinist Minister of Sport in Ukraine, Timofei Strokach, suppressed the story. In the Soviet Union, only state-sponsored acts of heroism were supported. For the Stalinist authorities, FC Start’s defiance of the Nazis was a problem on three counts. First, the footballers had actually agreed to play in the Nazi-organised league – possible collaboration. Second, their decision to beat the Germans was a spontaneous act and not approved by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union – this kind of individualism was a bourgeois tendency. Third, they were Ukrainians.

It was not until several years after Stalin’s death, in a 1959 Ukrainian book titled The Final Duel, that official recognition of FC Start’s heroic act was granted. The book recounted the story of the traumatic victory and the shootings at Babi Yar. According to British author Andy Dougan, a Soviet journalist then (in 1959) showed some (individualistic) initiative in discovering that the three ‘heroic’ FC Start players had been shot, not at Babi Yar immediately after the game but several months later. Because that new detail did not fit the new Soviet-approved myth of immediate, post-game revenge by the Germans, his ‘real’ story was dismissed at the time. The myth persisted.

The second question about the myth is to do with the importance of the deaths of four FC Start players. These murders represent just one very tiny incident in a war that led to the deaths of an estimated fifty million. In Ukraine alone, for example, Kiev was a city with a population of 400,000 in 1941. By the end of 1943 only an estimated 80,000 had survived the horrors of war. The rest of Kiev’s citizens were either dead, had been deported, or were refugees elsewhere in the wartime chaos. So, just how important is the tale of the Game of Death in the wider story of World War Two, Soviet tyranny and Nazi repression of Ukraine? What is its historical significance? How can we assess that?

In trying to answer that question about the character of the game itself and the actions of the FC Start players, there is one major argument. In the larger scheme of things, perhaps the game does not appear quite so heroic. Red Army solder and former athlete, Piotr Dinisenka, when hearing the army gossip about the game, took a sour view of the behaviour of the FC Start players.

While many thousands of my comrades are hungry and cold, and sitting wet in dirty trenches under Fascist bullets, somewhere my fellow countrymen, in a place far from the front, young and healthy lads, are playing football. They are playing with those who occupied our land and who have tried to eliminate and kill me and against whom I am fighting in inhuman conditions. I am sorry but how do you think I should feel about this, you do not expect me to applaud it?

Finally, there are other questions too? Why do you think the FC Start players did what they did? What was their motivation? Was it heroic? Was it impulsive? Both? Why were the Nazis so furious? Did the FC Start players realise the consequence of their actions? Do you think there was a direct connection between the game and their deaths? How can you find out more?

The Monument

Today, a monument to the FC Start players stands outside the Dynamo Kiev stadium. It was placed there in 1971 when the post-Stalinist repression was still active. It represents the struggle between two opposing political systems, Nazism and Communism, with Communism triumphant. Was that what it was? Can it be argued that it was a strange kind of triumph when, twenty-five years after victory over the Fascists, the KGB was still torturing and locking citizens up, censorship was still harsh and domestic travel was strictly limited by internal passports and permits. You could ask why, if the triumph of Soviet communism was so successful, did football teams that left the USSR for foreign competitions need their KGB guards to make sure that everybody came back? Did Trusevitch and the others die in vain?

|  |

A Problem: two images of supposed monuments to FC Start players. The left hand image is outside the Dynamo Kiev Stadium and comes from a private US Ukrainian websiteset up by Andrew Gregorovitch. It appears to show four muscular athletes (footballers?) in heroic poses.

The right hand image previously appeared on the British Council on its website and was described as follows ‘In 1981 a monument outside the Start stadium in Kyiv was built in their honour.’ There is no information available about the symbolism but it looks as if the heroic and naked Soviet athlete is crushing the Nazi eagle. The eagle was a key part of the Nazi military badges and was known as the ‘National Eagle’ (see beginning of this article).

A Question: Which image do you think is more likely to be the real one? Why do you think that?

An FC Start team member’s opinion

In 1992, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Goncharenko, then in his eighties, gave a frank interview, commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the Game of Death. Goncharenko’s unheroic view of the place of that famous match in history was quite clear:

A desperate fight for survival started which ended badly for four players. Unfortunately they did not die because they were great footballers, or great Dynamo playersÖThey died like many other Soviet people because the two totalitarian systems were fighting each other, and they were destined to become victims of that grand scale massacre. The death of the Dynamo players is not so very different from many other deaths.

Sources used in preparation of this article:

Andy Dougan 2002, Dynamo: Defending the Honour of Kiev, Fourth Estate, London

Sheila Fitzpatrick 1999, Everyday Stalinism, OUP, Oxford

Eduardo Galeano 1997, Football in Sun and in Shadow, Fourth Estate, London

John Keegan 1989, The Second World War, Pimlico, London

Aino Kuusinen 1974, Before and After Stalin, Joseph, London

Richard Overy 1997, Russia’s War, Allen Lane, London

About the author:

Associate Professor Tony Taylor is based in the Faculty of Education, Monash University. He taught history for ten years in comprehensive schools in the United Kingdom and was closely involved in the Schools Council History Project, the Cambridge Schools Classics Project and the Humanities Curriculum Project. In 1999-2000 he was Director of the National Inquiry into School History and was author of the Inquiry’s report, The Future of the Past (2000). He has been Director of the National Centre for History Education since it was established in 2001.

Tony has written extensively on various research topics including higher education policy, the politics of educational change, history of education, credit transfer processes and history education. With Carmel Young, he is co-author of Making History: a guide to the teaching and learning of history in Australian schools (2003).

(1) Ukraine

In 1941, Ukraine was one of the 15 republics of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), a collection of states united under Russian Communist leadership. The Ukrainians, who have their own language and culture, did not enjoy good relations with the Russians to the east. An example of this poor relationship was the oppressive banning of the Ukrainian language by Russian Tsars (Emperors) in the nineteenth century. The Ukrainians saw themselves as different from other Soviet citizens and there was a strong nationalist movement within Ukraine in the 1930s, which was both anti-Russian and anti-Jewish. Today Ukraine is an independent nation, divided politically between allying itself with Russia and tying itself more closely to the West. This split came to a head in a major political crisis caused by allegations of a pro-Russian rigged election result in November 2004.

Back to top

(2) purges

In the USSR, as was the case in Russia before the Revolution, there was a long tradition of rounding up political undesirables and sending them off to Siberia. In the USSR this process was refined as ‘purges’ or clearings-out of particular groups who might be regarded as enemies of the state.

Back to top

(3) NKVD

The People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs, the feared Russian secret police. Merged with the MVD (Ministry of Internal Affairs) in 1946, it was replaced in 1953 by the dreaded (and better-known) KGB (Committee of State Security).

Back to top

(4) Gulags

The Russians shortened Glavnoe Upravlenie Ispravitel’no Trudovykh (Chief Administration of Corrective Labour Camps) to ‘Gulag’. There were hundreds of labour camps in the Gulag, mostly in Siberia, a land of almost permanent winter. There, millions of people, criminals, ethnic minority prisoners, intellectuals and writers, politicians were imprisoned from 1919 until the mid 1950s. In 1939, at the height of its operations an estimated 3.5 million prisoners were enslaved in the Gulag. Untold hundreds of thousands, possibly even millions, died in the Gulag. The word has been adopted by English speakers to mean forced labour camp.

Back to top

(5)bourgeois

One of the greatest sins of any communist regime was to appear to be ‘bourgeois’ or middle class. ‘Bourgeois tendencies’ could be anything from wearing a suit to reading a book, and such acts of ‘individualism’ were seen as against the spirit of the Russian Revolution. According to the authorities they had to be stamped out. All too often, the accusation ‘bourgeois tendencies’ was an excuse for locking innocent citizens up and throwing away the key.

Back to top

(6) football match

In the Soviet Union soccer was increasingly popular because it was state-approved escapism. Another form of state-approved escapism at that time was cinema where, in the dark, Soviet audiences could, for a couple of hours at least, forget their daily troubles. In countries other than the Soviet Union, sport and cinema were also important ways of escaping the day-to-day worries. During the Great Depression in the 1930s, baseball and Hollywood kept US fans happy. In Australia, it was Don Bradman who lifted spirits in hard times.

Back to top

(7) Operation Barbarossa

Hitler had planned to attack the Soviet Union earlier than June 1941 but was held up by a tricky campaign in the Balkans and Greece. At first Operation Barbarossa (named after the red-bearded Frederick 1, medieval king of Germany and the Holy Roman Emperor) was a stunning success but the delayed start meant that the German armies were still short of total victory when the Russian winter set in late in 1941. After that, the German campaign slowly unravelled as the Soviet forces recovered and fought back. The original German plan had been to conquer Russia as far as the Ural mountains, take control of industry and agriculture and turn the people of the Soviet Union into forced labourers. Himmler, head of the SS calculated that this would mean the eventual deaths of 30 million Russians, Ukrainians, Jews and others, who would make way for German colonists. By early 1943, after the fall of Stalingrad to the Red Army, the Nazi forces began a long and demoralizing campaign of retreat that ended back in Berlin in April 1945. The Russians lost at least fourteen million soldiers and civilians between June 1941 and May 1945 in the war in the East, the bitterest and most costly campaign of World War Two.

Back to top

(8) Scorched Earth

A technique where retreating armies destroy houses, crops, factories, warehouses, railways to prevent an advancing enemy taking advantage of these resources.

Back to top

(9) Aktion

Literally an ‘action’ in German but can also mean a campaign. Aktion was the term used by German authorities to describe the rounding up of Jews, Communists and other ‘undesirables’ prior to their murder, either on the spot, or by transportation to a death camp elsewhere. Most Aktions in the East were carried out by four German Einsatzgruppen (loosely translated ‘Task Units’) of SS men who were divided into Sonderkommando (loosely, ‘Special Squads’) assisted in their brutal work by regular army (Wehrmacht) and recruits from the Latvia, Lithuania, Ukraine as well as from other occupied countries.

Back to top

(10) Babi Yar

Once a beauty spot but now infamous as site of a major Nazi atrocity. There are few photographs of the mass killings at Babi Yar, which is unusual since the SS and the Wehrmacht soldiers who were involved in atrocities were often keen to take photographs of their handiwork. Einsatzgruppe C was in charge of Babi Yar in 1941 and its commandant Blobel was hanged for war crimes in 1951. Back in 1943, the Nazis had returned to Babi Yar and used forced Ukrainian labour to incinerate the corpses of their victims, leaving tonnes of human ash behind, instead of clear, forensic evidence of their atrocities. Yevgeni Yevtushenko, a famous Russian poet, wrote a well-known poem about Babi Yar (1961) at a time in the Soviet Union when it was unusual and even dangerous to single out Jews as Nazi victims worthy of special mention.

Back to top