(Courtesy: road.cc)

One of cycling’s all-time greats, the Italian rider Gino Bartali, is set to be awarded the honour of Righteous Among The Nations for his role in rescuing hundreds of Jews during World War II, an undertaking he sought to keep secret during his lifetime.

| Entrance to the Garden of the Righteous (picture credit EdoM:Wikimedia Commons). |

The title is bestowed by the state of Israel on those who risked their lives during the Holocaust to save the lives of Jews, and others to have been recognised in this way include the Swedish diplomat, Raoul Wallenberg, and the German businessman, Oskar Schindler.

Recipients of the honour are awarded a medal and a tree is planted in their honour in the Garden of the Righteous at the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial in Jerusalem.

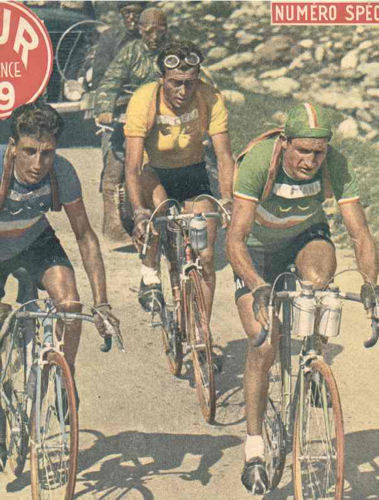

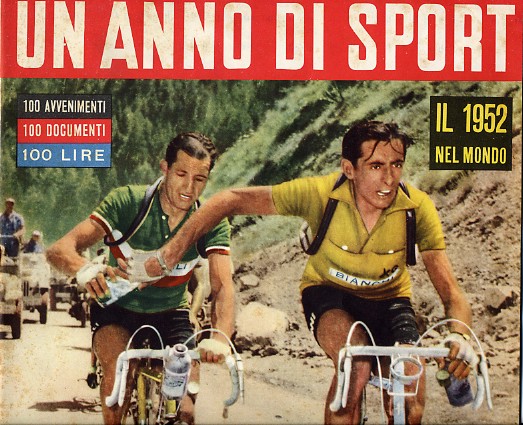

Bartali’s career spanned World War II, with the Tuscan native winning the overall titles in the Giro d’Italia in 1936, 1937 and 1946, and the Tour de France in 1938 and 1948. His rivalry with Fausto Coppi during that period divided Italy into two camps, those who considered themselves “bartaliani,” and those who were “coppiani.”

|  |  |

| Bartali right front (in green), picture courtesy of www.claudiocaprara.it | Picture courtesy of www.step.es | Bartali left, Fausto Coppi right, picture courtesy of www.calciofans.com |

A much more serious and deadly polarisation had split Italy between fascists and partisans as the war ended its closing years. After Mussolini was overthrown in 1943 following the Allied invasion of Sicily, German troops occupied Italy and nearly 10,000 Jews were deported to concentration camps, 7,000 of them dying there. Many more survived, however, thanks to the efforts of Italian oficials in obstructing deportations and individuals such as Bartali in supporting Jews in hiding.

During 1943 and 1944, reports the newspaper Il Sole-24 Ore, Bartali , nicknamed ‘Il Pio’ – ‘the Pious’ – undertook at least 40 long training rides, often between Florence and Assisi, on behalf of an underground network pledged to support Italy’s Jews, hiding documents and money in his bike’s frame and handlebars.

His son, Andrea, told the newspaper that his father would also go on training rides to Genoa, where he would pick up money that a Jewish lawyer had withdrawn from a Swiss bank account in Geneva, returning to Florence to distribute funds to Jewish families in hiding in Florence.

“Often, when he took me for a ride in the Apennines in Tuscany and Emilia-Romagna, he told me of the risks he had run, of when the fascist police stopped him, or of when he had to stop riding as the result of bombardment, taking refuge in the first useful ravine,” recounted Andrea.

Even after the war, however, Bartali insisted that his exploits remain secret, telling his son that no-one should know of them. In 2003, three years after the cyclist’s death, an Italian professional cyclist and political science student, Paolo Alberati, met Bartali’s mechanic, Ivo Faltoni, one of the few people who knew of his clandestine wartime activities.

That meeting led Alberati to research Bartali’s activities for his dissertation, during the course of which he undertook research in the archives of the State Police and the Ministry of the Interior, which revealed just how real were the dangers to which Bartali exposed himself.

“There,” explains Alberati, “I found files dedicated to Gino Bartali by police officers who had infiltrated the world of cycling and sports journalism, who spied on the champion and couldn’t explain the motive for those training rides that were hundreds of kilometres long.”

Coincidentally, the university professor who suggested to Alberati that he search those archives was the son of the surgeon who saved the live of Italian Communist Party leader Palmiro Togliatti following an assassination attempt in July 1948 in which he was shot three times.

Bartali’s victory in the Tour de France that same month is credited with having helped unite the Italian people during those difficult days, perhaps even preventing a descent into civil war.

Taking of the posthumous official recognition that his father is set to receive, Andrea told Il Sole-24 Ore: “The procedure followed by Yad Vashem is complicated and requires direct testimony from those who were saved, or at the minimum indirect testimony from their closest relatives.

“Some people have now responded to an appeal launched in this regard in recent months by an American journalist. In particlular, an 88-year-old woman from Viareggio who now lives in Tel Aviv and a lawyer from Florence, who told me, “I wouldn’t have been born if your father hadn’t helped and protected my parents.”